Just about every teenager gets copious safe-driving tips from their parents when they get their first driver’s license. But for black teens, the freedom and independence that comes with driving necessitates an added conversation — one often referred to simply as “the talk.”

This one offers advice for safely navigating potential encounters with police.

Motivational speaker Dwayne Bryant was inspired to write his book “The Stop: Improving Police and Community Relations” after having a positive encounter with an Indiana state trooper.

Bryant says the talk is necessary for black children and teens in particular because they bear a greater risk of harm in those interactions.

More: For Black Children, Learning How to Drive Steers Conversation to ‘The Talk’

“The reality is the community can do 100% of everything the officer says and they can still get killed,” he said. “That is the reality of being black in America. So what I do is I talk to them about many things, from understanding their rights to being respectful, but also understanding what their future is, because ultimately you do not want to have a 20-minute encounter derail 20 years of your life.”

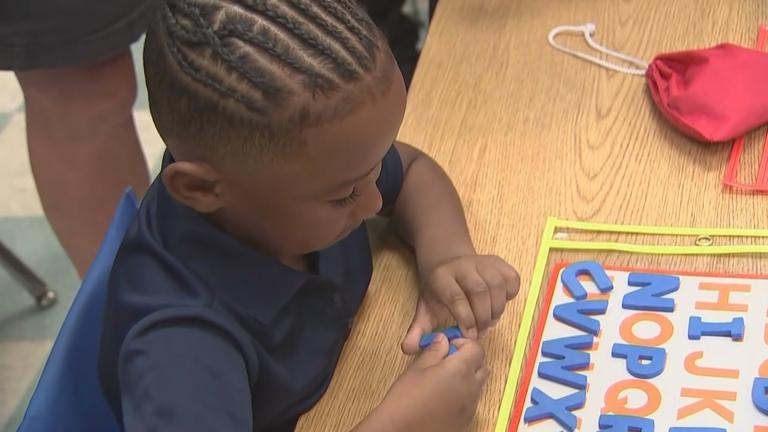

Child development specialist and Erikson Institute adjunct faculty Angela Searcy says “the talk” should not be just one talk, but a series of open-ended conversations throughout a child’s life — and not only black families should have them.

Searcy, the author of “Push Past It: A Positive Approach to Challenging Classroom Behaviors,” says it’s important to prepare all children for a world that often perceives black children differently from other children, and that having those talks can empower children, rather than scare them.

“Learning about racism and racial violence is not as scary as experiencing it … Just like a tornado can be scary, or a fire drill can be scary, if you know what to do when there’s a fire, you actually feel empowered,” she said. “Also not just talking about how black children may feel, but also including all children within this conversation that some children feel unsafe, what we can do about it, how we can support them, and how we can respond when there is a situation that is scary. This doesn’t lead to mental health issues, this actually stops us from having mental health issues.”

Reuben Jonathan Miller, associate professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration and the author of the forthcoming book “Halfway Home: Race, Punishment and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration,” says his studies of criminal justice policy and mass incarceration primed him for these discussions with his own children.

“Black children particularly and black people have been stripped of our innocence. The research tells us this, we know that police officers view black boys as older [by] four years on average, it reports them being [perceived to be] less innocent,” he said.

Along with advising compliant and respectful behavior towards police to his children, Miller says it’s “very important for me to let them know, sometimes, in fact often, you’re stopped for nothing that you’ve done at all. You’re stopped for just being, just hanging around. So it’s about working very hard to make sure they don’t internalize that it’s their problem, that it’s something they’ve done.”

And though black families have extra reason to speak to their children about police encounters, Miller says that when it comes to criminal justice, white families have every reason to have “the talk” too.

“Mass incarceration does not stop at the threshold of the black family. Thirty-nine percent of white boys will be arrested before they turn the age of 23 in this country,” he said. “So this is a national problem of epic proportions. Black folks are stopped at a much greater rate, but white families are not absolved from needing to address this crisis.”