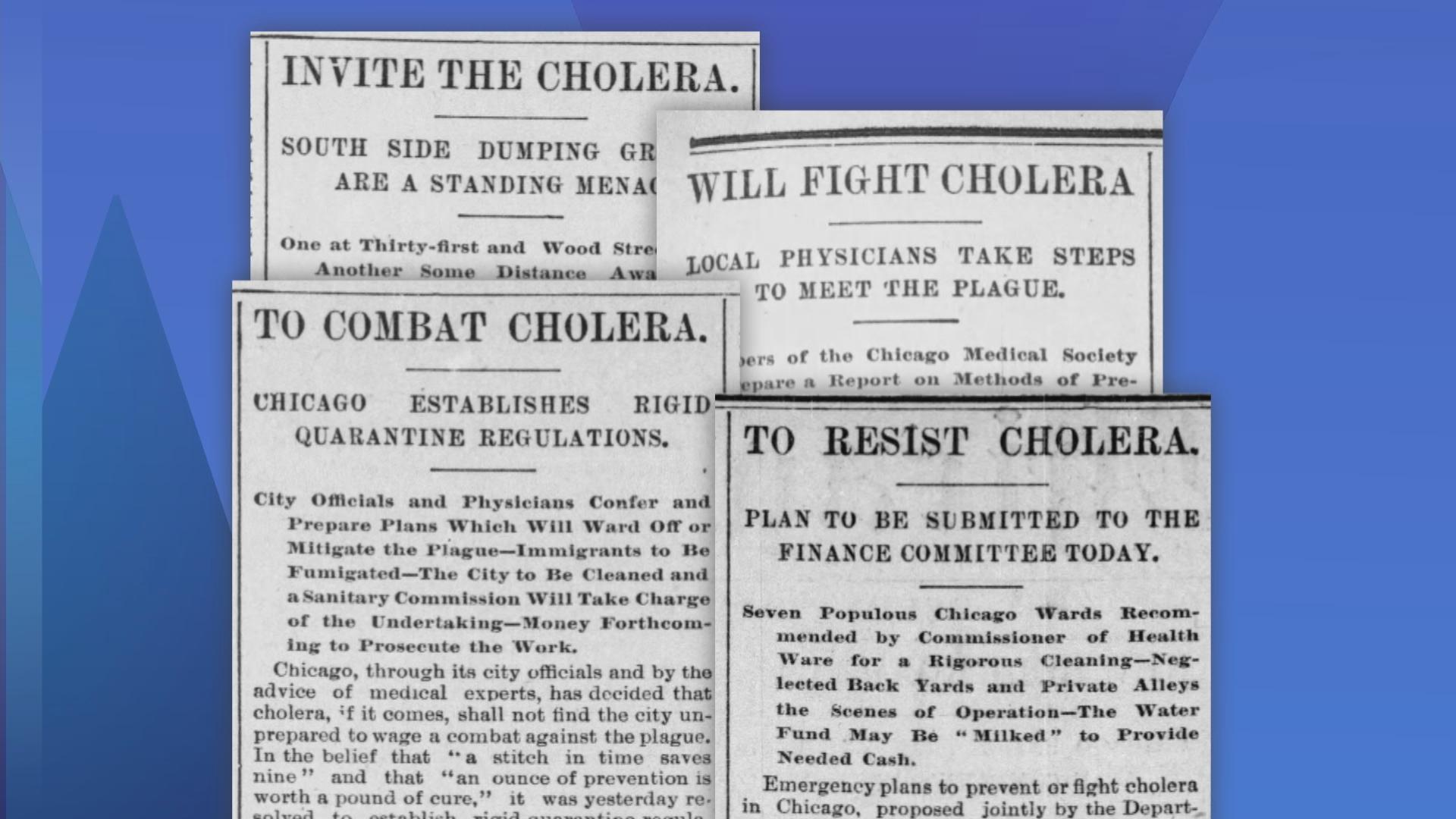

Coronavirus is far from the first public health epidemic to hit Chicago. The city struggled throughout the 19th century with repeated waves of the waterborne bacterial diseases cholera and typhoid.

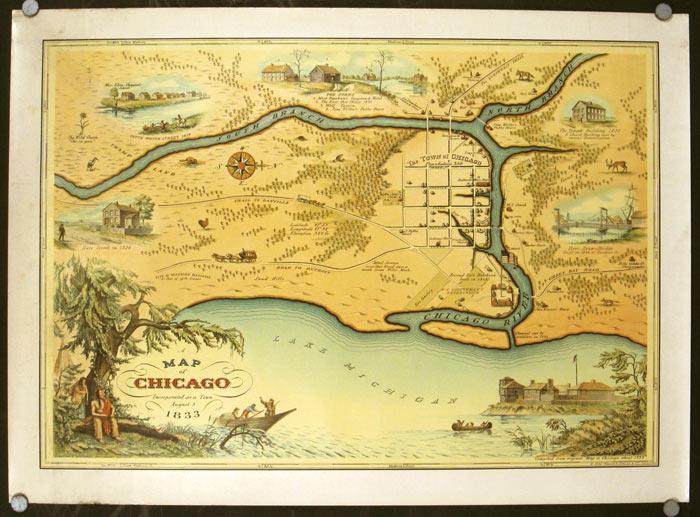

Cholera, which causes violent intestinal symptoms, would sometimes kill in a matter of hours due to dehydration. In fact, it was the threat of a cholera epidemic that prompted the city to create the Chicago Board of Health in 1835, just two years after Chicago was founded as a town. It still exists and advises the Department of Public Health, whose commissioner Alison Arwady has become very familiar to Chicagoans during the coronavirus pandemic.

What caused cholera was unknown at the time, but health officials did make the connection that unclean water seemed to spread it — and that was a huge dilemma because Chicago’s water supply comes from Lake Michigan, and back then the city’s sewage was dumped into the lake via the Chicago River.

Cholera arrived in the United States via a circuitous route from the Indian subcontinent to Europe during 19th century wars, to the New York area via immigrants.

It made its way to Chicago in 1832, when soldiers were dispatched from Buffalo, New York, to fight in the Black Hawk War. Worst of all, they were dispatched unnecessarily – the war was over before they arrived.

The worst major waves of cholera in 1852 and 1854 combined to kill at least 1,400 of Chicago’s 30,000 residents. There is a legend that an 1885 storm caused a wave of cholera that killed 90,000. That never happened.

Typhoid was another problem for 19th century Chicagoans. A yearslong outbreak of typhoid starting in 1891 killed around 2,000 and threatened the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The connection between tainted water and typhoid was known by then, and the city made great efforts to secure safe water for fair visitors.

What finally turned the tide against these waterborne diseases was overhauling everything about our water system. First, starting in the 1850s, Chicago built America’s first municipal sewer system, which required jacking up all of our buildings to a new higher street level. But the sewers still drained into the river, which flowed into the lake, so it wasn’t a complete solution.

Then we tried drawing our water from farther out in the lake. Men with picks and shovels dug tunnels under the bottom of the lake to carry clean water from offshore intakes. The iconic Water Tower on Michigan Avenue was part of this system. But as the city grew, sewage floated out to the intakes, so that didn’t work either.

Finally we decided to reverse the flow of the Chicago River. The huge Sanitary and Ship Canal opened in 1900, diverting our wastewater down the Mississippi past St. Louis. Sorry, Missouri. It still flows that way today, but now our wastewater is cleaned and disinfected before being released.

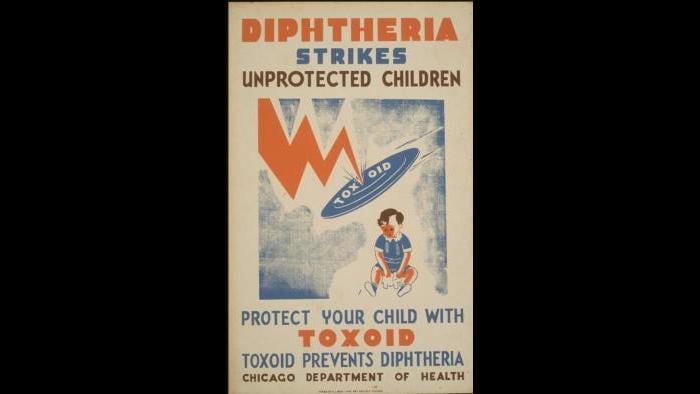

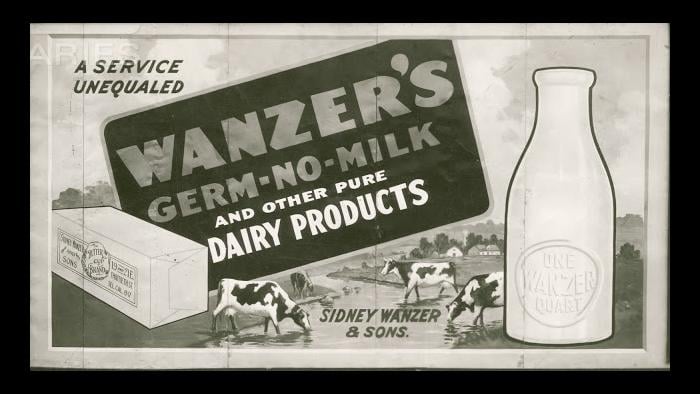

Even though those measures virtually eliminated waterborne diseases in Chicago, there were still other waves of disease that weren’t spread by contaminated water. Dysentery, scarlet fever, smallpox, diphtheria and whooping cough combined to kill thousands from the 1850s to the 1880s as the city’s population exploded with European immigrants. Then as now, it was the poorest people who suffered most due to run-down, overcrowded housing, a lack of sanitary infrastructure and, frankly, inequity in who gets access to health care. Those diseases began to abate around the turn of the century as vaccines were developed and food sanitation improved, including milk pasteurization and water chlorination.

In the early 1900s, tuberculosis was the leading killer. The Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium opened in 1915 to treat victims of the droplet-spread disease. Antibiotics were eventually discovered to cure such bacterial infections.

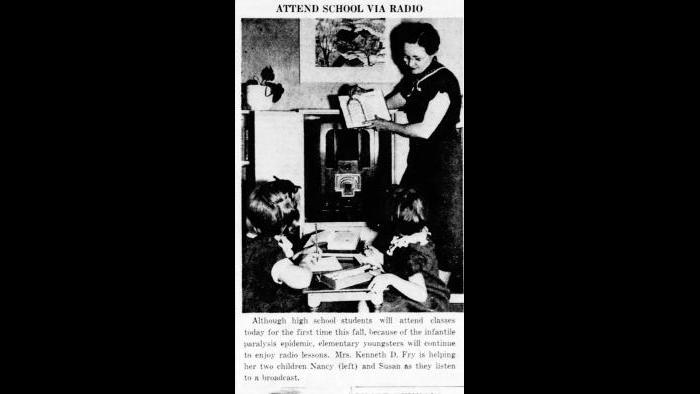

Two epidemics will feel more familiar to what we’re experiencing today – the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which we’ll tackle on Ask Geoffrey next week, and poliomyelitis outbreaks. Polio often led to paralysis and death, particularly in young children.

During outbreaks, just as we’re seeing today, schools were closed and public gatherings were banned. In 1937, the schools actually did a 1930s version of distance learning: school by radio. Polio was of course eliminated with the discovery of a vaccine in 1955 by Dr. Jonas Salk.

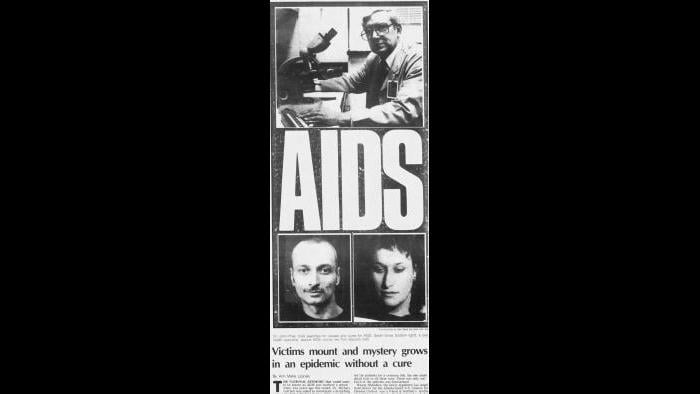

Until this current crisis, the last major disease epidemic was the appearance of AIDS in the early 1980s.

That’s caused by a virus, and there is no vaccine or cure, but the mortality rate has been greatly reduced thanks to advances in medical and preventative therapies.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.