Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin joins us for an inside look at Northwestern University's new $270 million athletic center and Jeanne Gang’s new environmentally conscious apartment tower in Hyde Park.

Kamin also gives us a new way to appreciate – of all things – jury duty.

Below, an edited Q&A with Kamin:

![]()

What does $270 million buy these days?

Kamin: It buys what turns out to be one of the finest athletic facilities in major college football, which is not exactly where you'd expect: Northwestern, once the doormat of the Big Ten, to be. But it buys a fieldhouse that is essentially an indoor practice field right along the shores of Lake Michigan. It buys also an athletics center that has a dining hall for athletes, classrooms for athletes and offices for athletic staff. It buys a lot. And in this case, it hasn't just bought facilities. It's really bought a very distinguished work of architecture.

In your article, you called it a "distinguished, sometimes breathtaking, work of architecture." For an athletic facility?

Kamin: Yeah, it really is, it is breathtaking. Indoor practice fields are typically like barns. They're just these metal boxes that go up anywhere and they're shut off from the world. This is entirely different. This practice facility, this fieldhouse has dramatic arches that support its roof which is essentially a dome. It's located right along the shores of Lake Michigan and it has a 44-foot high wall of glass that overlooks the lake. So, I mean, you know, you're in there running your sprints or punting, passing and kicking and you're essentially like right next to a beach and the waters of Lake Michigan. And it's pretty spectacular both from the inside looking out and also from the outside looking in. I went to take a look at it on Saturday night. And I mean, it's wow. Check out my Twitter feed. It's a beacon. It's really, really striking.

Chicago architect Jeannie Gang's apartment tower in Hyde Park was built to save energy, but you write that she turns the "prosaic task into muscular, visual poetry." Explain what you mean.

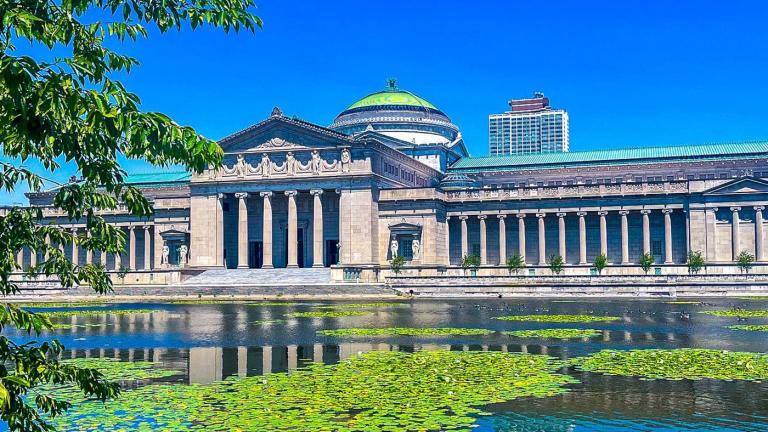

Kamin: What Jeanne did here really was to create a building with and for the shade. Basically what she did was angle portions of the south facing facade, the facade that faces the Museum of Science and Industry in Jackson Park. She angled those at precisely the angle of the sun on the day of the summer solstice. So, so what? Well, that means that there's less light, less harsh glare that penetrates into the living areas during the warm months. And those deeply recessed diagonal cuts also mean that there is more opportunity for the low lying sun in the winter months to create passive solar heating.

That's all nice and good and energy efficient, but you know what really sets this building apart is the way that those things come together to create a really powerfully sculpted exterior. And that's really what sets this building apart. Jeanne is best known in Chicago for the Aqua building with its kind of curvaceous balconies. And this is very different in many respects. I mean, the balconies shade the sun, they creative sculptural form. But this building is much more sort of traditionally broad shouldered. You know, in a Chicago way. It's tough, direct. It doesn't have that kind of sensual quality that Aqua does. But it has its own -- it's more about strength than sensuality. It's very good. I mean, it really does a lot of things very well.

So, you have fresh eyes on the Daley Center. Explain what you were able to see and appreciate when you spent a few days as a juror.

Kamin: Well, the exterior the Daley Center as one of the great modern buildings of Chicago. It's a building that forcefully expresses its underlying structure with this self-rusting Corten steel. It kind of has these muscular bridge-like spans between its cross-shaped columns. It's really a very powerful Chicago building. So, that's the exterior. It's really tremendous.

At the same time, unless you're a lawyer or a judge or part of a legal staff, you don't necessarily spend a lot of time inside. So what really struck me during the three days was just how well the building works. The lobby is a vast and very transparent space with high glass walls that really make it feel like the plaza outside is coming inside. You get great views of the structures surrounding the building. In the elevator lobby are these tall stone clad spaces that kind of quiet you and bring you into more a more contemplative atmosphere than a lively action on the plaza.

And the courtrooms are really well designed. They are compact. They are really trying to bring people into a dialogue, into a sense of community. The jury box faces directly toward the contesting parties. There are all kinds of understated but beautifully worked out details like the solid oak door that's probably 12 feet high that leads into the jury room. Or the brass foot rails in the jury box. All these things kind of communicate dignity, the seriousness of the task at hand and yet they don't do it with classical or traditional architecture. They do it with mid-20th century modernism. So there are no like bas-relief sculptures of the scales of justice. But the proportions and refinement of the materials, the careful arrangement of the spaces all work really well. So, it was a great experience. Thomas Donnelly, the judge presiding in our case, very much appreciated the design of this courtroom and was happy to talk about it afterwards. You know, only in Chicago, do you get a judge who is like a docent who gives the architecture critic a little lesson in the beauty in the courtroom.

Related stories:

Archaeological Dig at Gray-Cloud Home Attracts Neighbors, History Buffs

The Rise of College Dorm-Style Co-Living in Chicago

Blair Kamin: Union Station Redevelopment Off Track