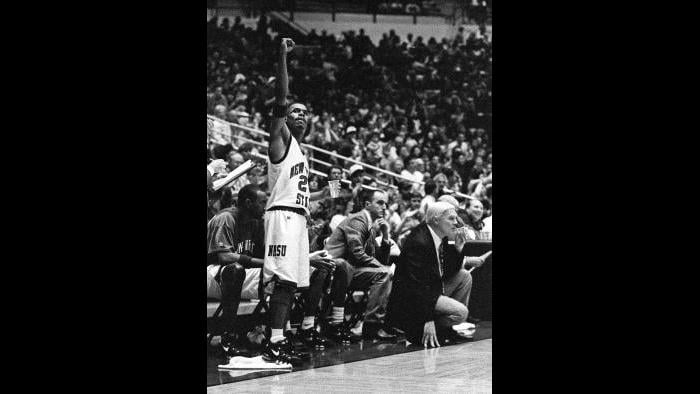

The 1994 award-winning documentary “Hoop Dreams” featured some young Chicagoans with big hopes for their future. In one scene, a sophomore at Marshall Metropolitan High School is shown on the team bus. That young man is Shawn Harrington.

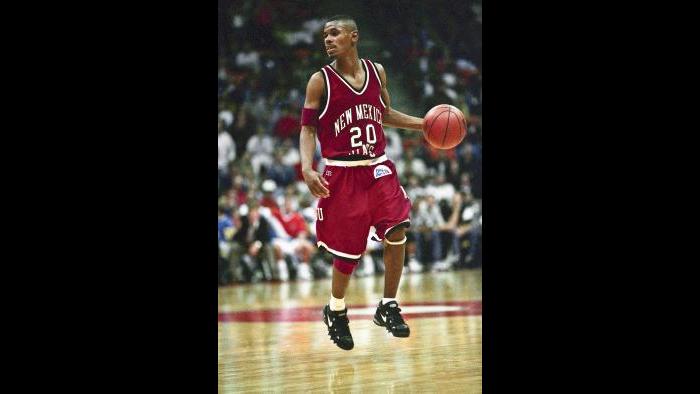

Harrington went on to play basketball at New Mexico State before returning home to raise his daughter and work in the community.

And it was here in Chicago that Harrington was the target of mistaken identity when he was shot in his car and left paralyzed while protecting his daughter.

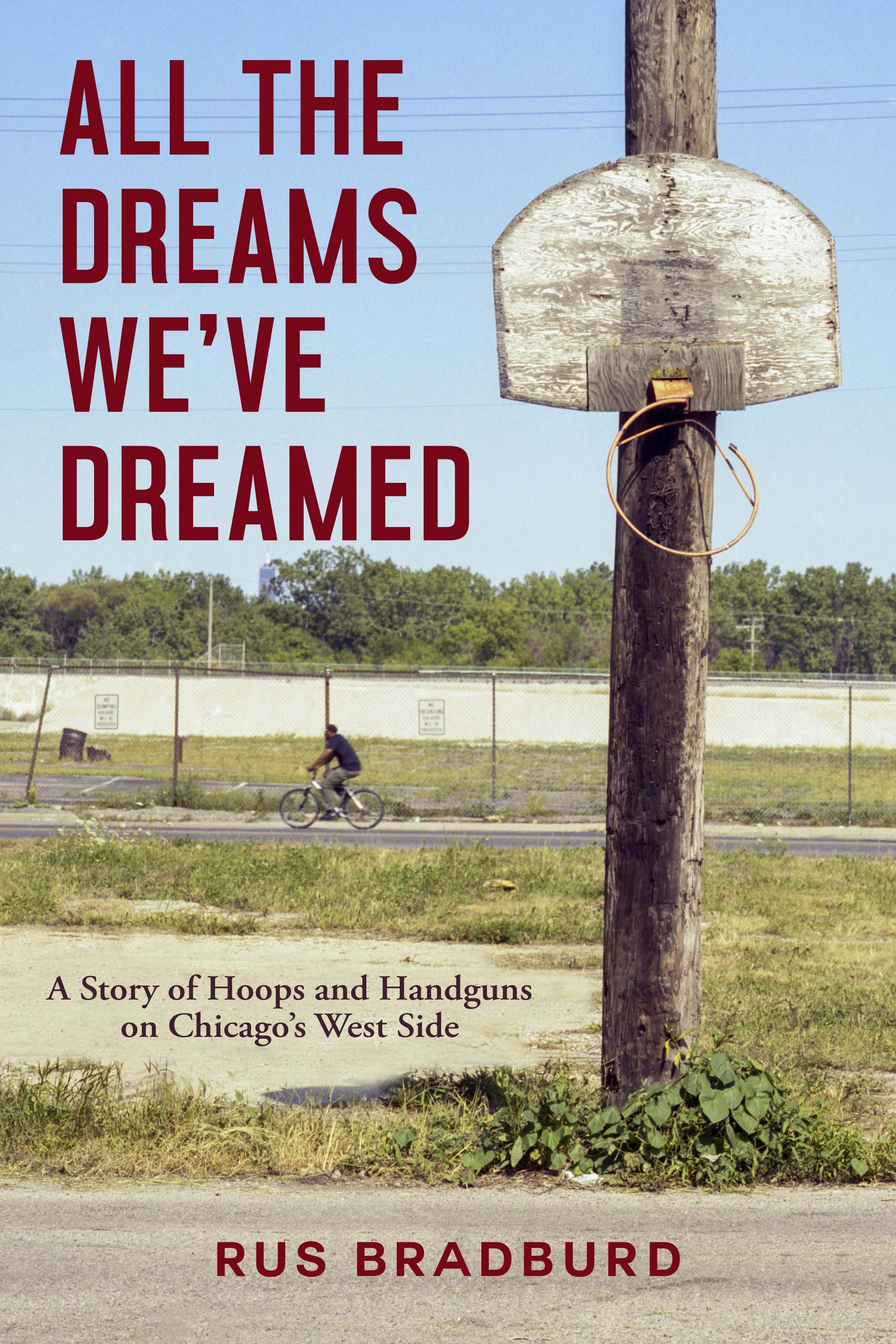

Harrington is at the center of the harrowing but hopeful new book “All the Dreams We’ve Dreamed: A Story of Hoops and Handguns on Chicago’s West Side” by Rus Bradburd, his former New Mexico State coach-turned-author.

Bradburd joins us in conversation.

Below, Chapter 1 of “All the Dreams We’ve Dreamed.”

![]()

Shawn Harrington couldn’t find his car.

After a decade at Marshall High School on Chicago’s West Side—as a student, teacher’s aide, and basketball coach—he had spent enough time in every corridor and classroom that his memory sometimes blurred. On the morning of January 14, 2014, he had hustled up three flights of stairs to keep from being late and tossed his coat onto the back of a chair in the special ed office. Now, after practice, he wondered if he misremembered parking behind the school.

Shawn was the varsity assistant under a man named Henry Cotton. Younger looking than his thirty- eight years, Shawn enjoyed an enviable level of trust and communication with students and players. He was open, friendly, and he knew when to joke and when to back off. He had overcome so much in his personal life that he was empathetic and compassionate about the struggles typical to Marshall kids.

Shawn was the varsity assistant under a man named Henry Cotton. Younger looking than his thirty- eight years, Shawn enjoyed an enviable level of trust and communication with students and players. He was open, friendly, and he knew when to joke and when to back off. He had overcome so much in his personal life that he was empathetic and compassionate about the struggles typical to Marshall kids.

Shawn checked on Adams Street, but his 2001 Expedition wasn’t there, either. He cursed under his breath. The Eddie Bauer edition Ford SUV was his first decent car, a distinct two-toned job, light blue with a tan stripe. He had bought it used in 2012 for $3,500, a birthday present to himself. The car was functional, noticeable but not flashy, and he could fit seven Marshall players inside, eight in a pinch. It wasn’t paid off yet, but it was insured. Or was it? An anxious moment passed as he tried to remember if his insurance was up to date.

Prior to the purchase, his travel routine was a taxi to Marshall, then the Green Line “L” train or CTA bus home. That simple travel schedule used to cost him about sixty dollars a week. He didn’t relish even a temporary return to public transportation, although it was cheaper than the combination of car payments, insurance, city sticker, and gasoline. The car, however modest, was a sign that this kid from the neighborhood had made good. Besides that, the car was crucial. It allowed him to drive his oldest daughter to school every day, and it served as a sort of rolling counselor’s office for the players he drove home after practice each night.

Where had he left it? Rather than ponder his dilemma in the winter chill, he went back inside to the main office. Not until he jiggled his coat pocket did he connect the dots: his car was gone, and so was his second set of keys. On the coldest days, Shawn brought two sets. He would fire up his car after practice, lock up with the second set of keys, and run back inside to see which players needed a lift.

“Somebody stole my car,” Shawn told security guard Tyrone Hayes outside the main office. Hayes greeted kids coming into school, checked IDs as they marched through the metal detector, and made sure the students were in their required uniforms. He had held his job for thirteen years, spent time as a coach, and, like Shawn, been a terrific player for Marshall. On patrol in the hallways much of the day, he kept an ear to the ground. Sympathetic about the car, he figured Shawn didn’t need him, so he punched out to go home.

In the main office, Shawn found himself on hold with the police department’s nonemergency number. Somebody stole his car right off Marshall property? He couldn’t believe his bad luck. Minutes later his cell phone buzzed. It was Hayes. “What’s your license plate number?” he asked. Shawn hung up on the police and rattled the number off.

“I’m behind your car now,” Hayes said. Driving north on Kedzie Avenue, he had noticed the Expedition parked facing south and swung a quick U-turn. In Shawn’s car were two brothers known to school authorities as “the Twins.” One sat behind the steering wheel, the other rode shotgun. The identical sixteen-year-old freshmen at Marshall already had a history of trouble and arrests.

The twins recognized Hayes and the Expedition bolted back onto Kedzie, heading south. After a few minutes on their tail, all the whilegiving Shawn the play-by-play, Hayes again pulled next to the car, honked, and rolled down his window. “Yup, it’s the twins for sure,” he yelled into his phone. “Two more knuckleheads are in back.” Hayes moved slowly alongside, nearing a stoplight, waving and pointing. Pull over! He didn’t want an angry confrontation—who knew what the boys carried in the car with them?— although he figured it would not come to that. Hayes believed the twins understood he was a peacemaker, a compromiser, even if he ruined their joyride.

They took off again. Hayes continued to tail the SUV, winding down side streets. Soon the boys were sailing through stop signs and roaring through red lights. Hayes followed suit until they busted out of an alley onto a crowded street. He halted rather than risk an accident. He had kept Shawn on the phone the entire time. “I lost them,” Hayes said. “I’ll just call the cops again,” Shawn said. “At least we know who did it.” Hayes said, “We’ll get the car back when we see the twins at school.”

The next morning, Shawn shared a taxi with his eldest daughter, Naja, whom he dropped off at Westinghouse College Prep, less than a mile from Marshall. Naja aspired to have the highest grade point average in her sophomore class and she hated to be even one minute late.

Back at Marshall, Shawn waited, seething, by the metal detectors with Hayes until the late bell rang. No twins. He trudged upstairs. Shawn worked as an ESP (educational support personnel) in special education. He had earned his college degree in communications, but he did not have a teaching certificate. ESP workers make about $32,000 a year and are not part of the powerful Chicago Teachers Union. It’s not a bad job—the nine-month schedule gave him plenty of time in the summer to be with Naja and Malia, who was eight.

The Marshall building, well over a hundred years old, didn’t have an elevator, but he liked the intense forty-second leg workout hoofing up to the third floor. He’d climb those stairs as many as a dozen times daily. On this day it seemed a long way to the top.

For three days Shawn took a taxi to work, with no clue as to his car’s whereabouts. Finally, on Friday morning he got a call from the main office. Tyrone Hayes had nabbed one of the twins.

State Farm would reimburse Shawn the entire cost even if the vehicle were never recovered, so why was he so angry bouncing back down the stairs? He calmed himself as he approached the office. One deep breath, then another, the way he’d always done before sinking an important free throw. It was just a stolen car.

Hayes couldn’t get over the theft, either. Ballers and coaches had often enjoyed a protected social status in the neighborhood. “I bet the good twin might show us where they dumped the car,” he said quietly to Shawn before they went inside the office. Hayes thought of the pair as “good twin” and “bad twin.” One instigated the trouble and the other would get dragged along. Hayes believed that was how the theft had gone down—and that dynamic would now help authorities recover Shawn’s car. The good twin had already fathered a child and was a little less inclined toward mischief.

In the main office, a policeman, a detective, and two school administrators had the good twin cornered. Sure enough, the boy quickly came clean. Sure, he went along for the ride, but he denied stealing the car.

“You’re not talking about me,” he said, “that’s my brother, and I always get the blame. I wasn’t the driver.” He admitted they dumped the car very close to Westinghouse, less than a mile away. Shawn’s palms got sweaty at the mention of Westinghouse. He knew enough not to blurt out anything about driving Naja there every day. Protective of his children, the last thing Shawn wanted was this troublemaker to know he had a daughter the same age. An administrator, two policemen, and Shawn drove the good twin toward Westinghouse. It turned out the car hadn’t exactly been “dumped.” It was parked perfectly at the corner of Franklin and St. Louis, ready to be fired up for the next joyride. The twins had somehow disabled the theft prevention chip, so Shawn’s set of keys no longer worked. Only the thieves could restart the vehicle. The good twin insisted he did not know who had kept Shawn’s swiped set of keys. The police didn’t buy the boy’s story, or at least not his claims of innocence. They took him away in handcuffs.

Shawn called State Farm again, this time to get the Expedition towed. The agent reminded him that his policy included the use of a rental car from Hertz, so at least there was that good news. He could return to his routine of driving Naja to school and his players home after practice.

That afternoon, Shawn learned from his students how easily his keys had been lifted. Special ed shared an office with nursing and psychology, so a stream of foot traffic passed through. He remembered now: he had carelessly flipped his coat over an office chair, leaving it exposed to dozens of kids each time the bell rang.

The bad twin had even bragged about having a car to goof around in after school. He’d had the nerve to take Shawn’s keys to the third floor window and hit the panic button. When he figured out which one had lights flashing below, he must have memorized the parking spot and quickly shut the alarm off. Although some students saw this happen from their seats, they assured Shawn they’d had no way of knowing it was his car down below.

A week after the theft, Shawn got a ride to the Hertz rental car office on Western Avenue, less than a mile from Marshall. He was disappointed to learn Hertz couldn’t loan him an SUV, or anything else that might carry half the varsity basketball squad. Instead, the clerk walked him out to a white sedan. But then Shawn couldn’t believe his luck—it hadn’t occurred to him that he’d get a nearly new model. He would manage with the four-door SS Impala, a standard and nondescript car.

It had been a hard winter for Shawn. The combination of special ed duties and basketball practice often left him exhausted. The timing of the car theft was the worst part—in mid-January, when Marshall had lost three games in a row (not counting a forfeit win).

The Marshall team, a city powerhouse, was struggling uncharacteristically, with a record of 5‑7 midway through the season. Shawn knew their fortunes were about to change, though, because three days earlier, Tim Triplett had finally been declared eligible. Triplett chipped in nine points his first game, a few days before the car was stolen, but that close loss was a small pothole. Shawn believed Triplett would get the team straightened out.

Their new senior guard was quick off the dribble, feisty, strong with the ball, and a natural leader—like Shawn had been in his playing days. Triplett wasn’t Marshall’s point guard in the sense that he always dribbled the ball up the court, but he was clearly in charge, and that began with him directing the team with his voice. Shawn had also been a fearless point guard, a crafty ball-handler, a leader—although not nearly as loud or brash. Triplett, Shawn figured, was precisely what the team needed, and although he stood just five foot nine, his swagger and confidence was highly valued in Marshall’s rugged Red West conference. Like any coach who’d played in college, Shawn was constantly analyzing their new star’s potential. Triplett was small, but could he still play at the next level? No doubt. At a big state school? Maybe. Just maybe, after attending junior college, as Shawn himself had done when his ACT test score came up one point short.

Triplett was a double transfer: he left Crane High School near the end of his junior year, finished the semester at Farragut, then transferred again to Marshall to start his senior year. He told everyone he left Crane because his coach took another job. Besides, Crane had been designated as a failing “turnaround” school. He’d left Farragut, he said, because he had gotten in a fight.

Transfers are disturbingly common for players in Chicago’s Public League, but Triplett’s ineligible status for the first half of the season was a bit of a mystery with West Side coaches and players. He missed Marshall’s first dozen games, while his new coaches had tried to keep him focused on bursting out of the gates when his eligibility was finally approved.

On the surface, sitting out the first half of the season barely deterred Triplett. With a charisma that even the Marshall seniors had to respect, he helped direct the team during timeouts and halftime still in his street clothes.

Gossip usually got back to Shawn, partly because Marshall was so small these days. Its enrollment had plummeted to just over four hundred total students. Lately he’d heard talk in the hallways and lunchroom where kids and teachers mixed freely that occasionally Triplett’s boisterous personality rubbed people the wrong way. That was surprising.

With the coaches, he was nothing but respectful, and he seemed to have always been a Marshall player.

A coach isn’t supposed to have a favorite player, especially a first year guy, yet it was nearly impossible not to be taken with Triplett. It was just a coincidence that Triplett wore number 23, as Shawn had worn at Marshall in the early 1990s. Shawn did not realize how much more history they had in common.

In the fall of 2013, all predictors pointed to another typical Marshall team: small, quick, overachievers. The center for the Marshall Commandos would be the six foot four, lanky, dreadlocked James King. Their best returning player was six foot two Citron Miller.

Because the new kid, Tim Triplett, was practicing with them from day one, nobody realized what became obvious once the games began without their new transfer in uniform: the team lacked the heart and arrogance it took to win on Chicago’s West Side. Shawn had been grooming Triplett to fit into the Marshall system, showing him the fine points of the offense, when to be careful of over dribbling, reminding him of the rotations on their presses. In some regards, this fine-tuning was secondary. “His point guard skills, we already had that,” Shawn says. “What we were waiting on, what we needed, was Triplett’s point guard attitude, his vocal leadership.”

The Commandos, like anyone Triplett interacted with, became hyper aware of his voice. Because of this, Shawn worried Triplett might clash with Citron Miller, who was also a big talker. Miller was the team’s most skilled and versatile player, and he began the season with major expectations—this was supposed to be his team, his year to shine. Nobody could deny that Triplett added something fresh, but the coaches were concerned that there might not be enough shots to keep everyone happy.

Having two different voices on the court and locker room, Miller admits, could have been touchy. “Tim had been such a strong leader at Crane,” he says, “but we set all that aside. I still got my points, but Tim, he was all heart, the motor person. He brought fire to the game.” Splicing in a transfer can be problematic even for a quiet kid, particularly in a program with a complex defensive scheme. Marshall’s gambling strategy usually meant pressing and harassing their opponent the entire length of the court, often doubling teaming, or “trapping” the ball.

But Triplett’s ability to switch allegiances and fit in quickly had more to do with his mindset than his skills.

“From the first day of practice in the fall,” Shawn says, “I was thinking about Tim Triplett’s future,” meaning much further down the line than his high school or possible college basketball career. Past the inevitable end of Triplett’s playing days. Past the all-too-common illusion of an NBA career. “I believed from the start that Triplett could be a coach someday,” Shawn adds. “The kid was a pure leader with just the right amount of fearlessness.”

Shawn preferred players who needed to be calmed down, not ratcheted up, and Triplett’s engine ran in overdrive. Shawn might need to whisper to Triplett to relax, settle down, but that was preferable to having to motivate a timid kid. Triplett’s hyperaggressive instincts made him a natural fit for Marshall’s traps, but sometimes it could get him into trouble, leave him vulnerable. In some fundamental way the headstrong guard was already beyond the coaches’ control.

This mentality would be on full display in the first conference matchup Triplett would play—or that’s what the coaches hoped. Triplett had already sat out a total of eleven games when he took the court for the first time on January 11, 2014, a close nonconference loss to East Chicago High School of Indiana, but the score and Triplett’s obvious impact was seen as a good sign.

Then Shawn’s car was stolen on January 14, just a few days before their next game, against conference rival Farragut, the school Triplett had briefly attended, and everyone anticipated a rush of adrenalin on both sides with plenty to prove. The Commandos were now trying to turn around a three-game losing streak. Nobody at Marshall was concerned about getting their new player motivated, though, because Triplett took things to an extreme. “Triplett wore whatever uniform he wore with pride,” Tyrone Hayes says. “It was as if he was claiming This is my team! And if Triplett played against you, he’d feel the same way once the game was over. You don’t play with me, ain’t no love for you. That’s the way he would act.”

Might this all mean there would be trouble with Farragut on the court? It could have. But Triplett did not compete: he had yet to be certified eligible for Public League play. An Indiana school had no idea about the Commando roster, but Farragut’s coach certainly would. However, even with Triplett on the bench, Marshall won convincingly, 76–65.

Despite Triplett being yo-yoed around, Shawn was in good spirits after that game and didn’t even mind not having the Expedition for the players to pile into.

The good feeling carried over into the next matchup on January 18, as Marshall beat nonconference North Chicago in a close contest in the Martin Luther King Tournament. Triplett, who’d taken to wearing a conspicuous white headband, only had two points, but he quickly established himself as the best defender on the court, recording a half-dozen steals to go with as many assists. The locker room was abuzz after that one—they’d gotten the team turned around.

Two days later, the Commandos hammered Indiana school Gary Westside by twenty-five points, with Triplett scoring ten. They were ready to live up to the Marshall legacy. Coach Henry Cotton recalls the new Marshall guard was flying by this time. “We just had to put Triplett in the right spot, and he’d watch and learn fast. He knew what every guy was supposed to be doing.” Naturally, Triplett didn’t hesitate to share that knowledge.

It was freezing outside, but the team seemed immune, as if the exhilarating buzz from the modest three-game winning streak insulated them.

Colder weather, an “arctic blast,” had been forecast for the following week, which prompted Shawn to quit procrastinating. He got a lift the next day from Tyrone Hayes to the nearby Hertz dealership, and he drove off in the nondescript white Chevy Impala.

Shawn and his fifteen-year-old daughter had plenty to talk about on their January 22 morning commute. Westinghouse High School, where Naja had earned a spot on the frosh-soph cheerleading squad, was Marshall’s opponent that afternoon, and she’d be on the sideline for the rematch. Plenty of good-natured teasing went down between father and daughter. “We beat you last game,” she reminded him for the fourth time before she jumped out.

Temperatures had indeed dropped, and Shawn didn’t mind his daughter diverting his attention from the cold, even when she stood with the car door open and leaned her head in, bracing herself with her left hand against the headrest. Her tone changed this time: “See you after school, Daddy.”

Yes, Westinghouse had won before Christmas, but Shawn figured it would be different this time, and he was correct: Marshall won, 64–58.

But Westinghouse was a Red West conference opponent too, and certification from downtown concerning Triplett’s eligibility was still not resolved. Westinghouse, like Farragut, would have been hyperaware of his issues and Triplett did not play. It was the thirteenth game he would miss as a senior.

The Commandos now had a four-game winning streak—nothing to brag about, but still a distinct turnaround. They had a chance to extend their winning streak to five when they faced private school Providence-St. Mel on January 26. Triplett’s eligibility certification issue was finally resolved. He wouldn’t miss another game.

The matchup would be intense partly because Triplett’s pal from summer ball, Tevin King (no relation to Marshall’s James King), was St. Mel’s star guard. Tevin King, a bit over six feet tall, drew the assignment of guarding his friend. He was respectfully cautious, knowing his height advantage could be neutralized by Triplett’s quickness. King had great affection for Triplett. “Tim could be really funny off the court,” he says, but on the court that all fell away. “He had the little man syndrome,” King says, something that manifested in Triplett’s scrappy play and nonstop chatter.

With the score tied in the fourth quarter and emotions running high, Triplett stole the ball and had a breakaway layup. But King chased him down and soared to block Triplett’s shot at the last instant. The play was a shocker—an easy basket denied and Marshall’s good fortune dramatically erased. The crowd erupted, momentum shifted, and St. Mel won 64–61.

Despite his eligibility issues and the seemingly endless paperwork from downtown, the Marshall coaches were more than happy with their new player. Triplett never missed a practice, was never even late.

This is unusual, considering most Chicago Public League teams practice or play six to seven days a week once the season is underway and many players have problematic home lives. “Triplett would have kept practicing, too,” Cotton says, “until he was made to stop and we had to lock up.”

One day at Marshall in the middle of a class period, while Cotton was just outside the main office on his security patrol, Triplett sprinted up. “Coach!” he gasped between breaths, “we’ve got a fight—broke out— in our classroom!”

Cotton and Triplett hustled upstairs, where the pugilists were separated. Triplett’s actions impressed the coach. “Tim was often the peacemaker,” Cotton says.

Marshall played Whitney Young High School on January 29. A selective enrollment magnet school, Whitney Young is an academic bright spot for CPS and often gets held up as a model, as if every Chicago Public League team could produce both a great basketball team and the best ACT scores in the entire state.

This was the first Red West opponent that Tim Triplett faced, but Whitney Young was so loaded with talent that they were hardly bothered by the chattering little guard: their center, six foot eleven Jahlil Okafor, would be an NBA star within eighteen months. Triplett scored ten points, but Marshall was badly outsized. (In the first matchup, the Commandos had lost by twenty-seven without Triplett.) Losing 75–57 to a nationally ranked team was no disgrace, and Triplett had made a difference—just not enough.

Their next game at Orr High School was winnable. But Marshall had now lost two in a row.

On January 30, 2014, head coach Henry Cotton arrived at Marshall early to get in his morning walk. It was twenty-three degrees outside, but the windchill made it feel like nine degrees—a day to get his exercise inside. Cotton called Shawn Harrington on his cell phone before the first period bell, as he often did. Shawn was in the rental car, waiting for Naja to come out and begin their morning commute.

Cotton and Shawn typically discussed what needed to be finetuned: zone offense, out-of-bounds plays, press breakers, or any problems within the Commandos team. Ten days ago it felt like the cloud hanging over their season had lifted, but last week the losses to St. Mel and Whitney Young set them back again. Shawn told Cotton,

“I’m heading your way now” as Naja appeared with her book bag and climbed in.

Later, after the first bell had rung, Cotton was back walking the hallways, his typical security patrol detail, when he saw the ROTC director weeping. She ran down the hallway and into the faculty washroom.

Cotton thought it was odd, but before he could investigate, one of the players was at his side. “When was the last time you talked to Shawn Harrington?” the kid asked.