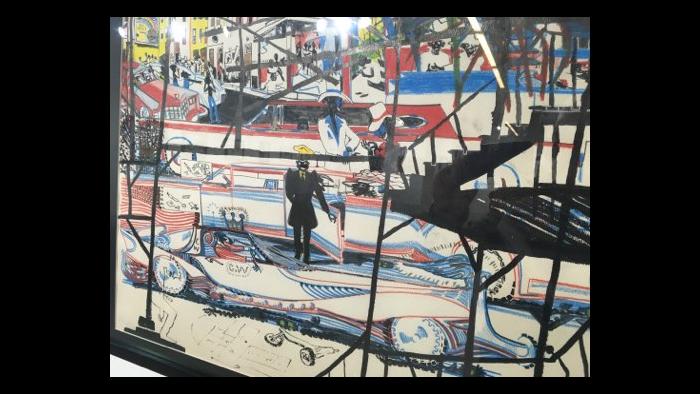

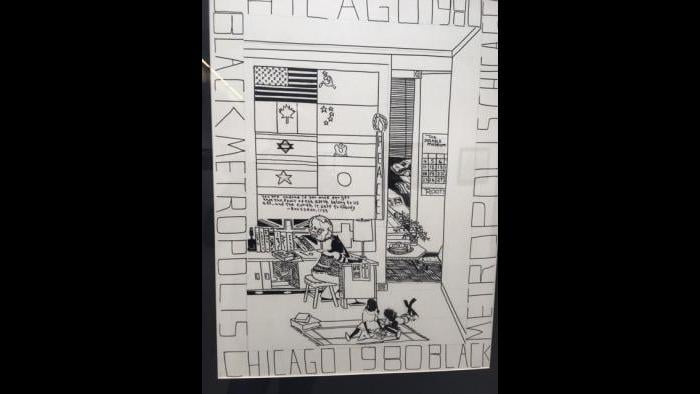

An exhibition looks at rare works of art that are powerful and sometimes graphic. The historic work was made by an artist with a strong connection to Chicago public art.

Bill Walker was a muralist on a mission to display beauty and culture, but he also reflected on the harsh realities of life on the streets.

We take a look inside the exhibit “Bill Walker: Urban Griot” at the Hyde Park Art Center through April 8, 2018, part of the Terra Foundation for American Arts’ Art Design Chicago Initiative.

TRANSCRIPT

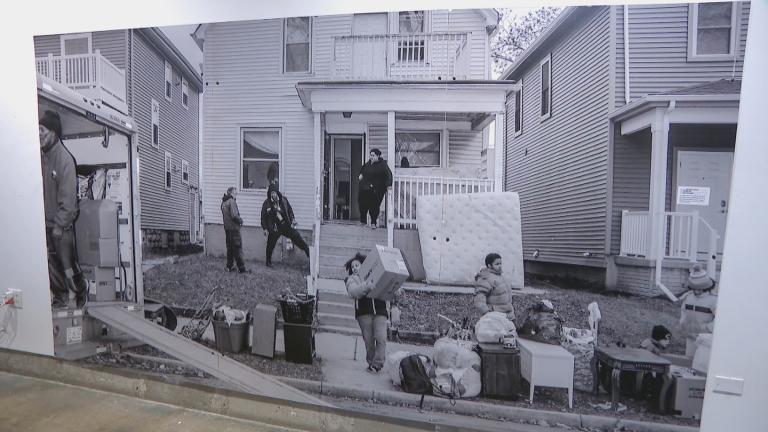

Phil Ponce: There are positive portraits of happy families, and threatening images of street life and despair.

At the Hyde Park Art Center, a selection of rarely seen works is on display.

They were created by Bill Walker, who once stated: “The artist and his art are warning man of the dangers ahead.”

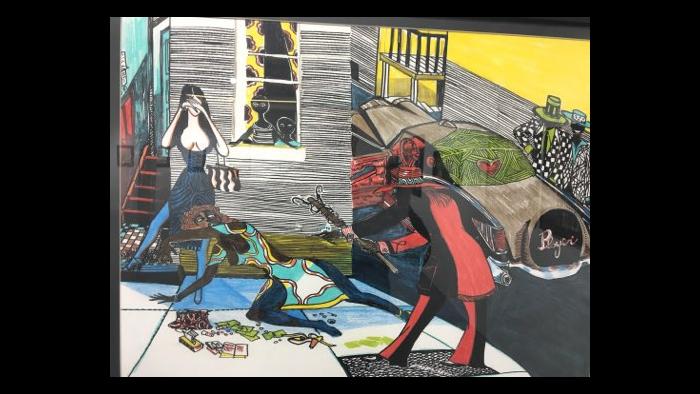

Juarez Hawkins, curator: In a lot of these images you’ll see pics of children and they’re sort of bearing witness to a lot of the carnage or the violence that’s going on, so in a way he’s saying “I’m gonna keep this real, because this is where I live.” He lived in these areas, so “I live here, this is my lived experience, and I see these children all around me” and it’s their lived experience as well.

Ponce: This exhibition of Walker’s art from the 1970s and ‘80s is called “Urban Griot.”

Hawkins: In West African culture the griot is the person who passes on the culture. Oftentimes if you’re dealing with cultures that don’t have a written language, the way you pass on the legacy and history of a given tribe or culture is through the storyteller or the griot, and he or she would be the keeper of the stories that are continued to pass on throughout the generations. So I looked at the work and I felt it was in that same vein, this idea of someone telling a story that was very topical and relevant in the ‘80s, but interestingly enough it’s still topical and relevant even today.

Ponce: The pictures are often cautionary tales, created by an artist concerned about the plight of his neighbors.

Hawkins: Basically the work is divided into three main series. The first series is called “For Blacks Only” and a lot of it was directed at the black community. It was a way of saying, “Hey, look at what’s happening in our communities, the violence, the gangs, the drugs. Maybe we as a community should hold ourselves accountable too for the state of our affairs. At the very least, be aware of what’s going on and not be blind to it.”

The second series is called “Reaganomics” and that’s dealing with the economic impact of Reagan’s policies on the poor. We hear a lot about the tax breaks and so on ... and a lot of social services were cut, and it really had a devastating impact on communities of color.

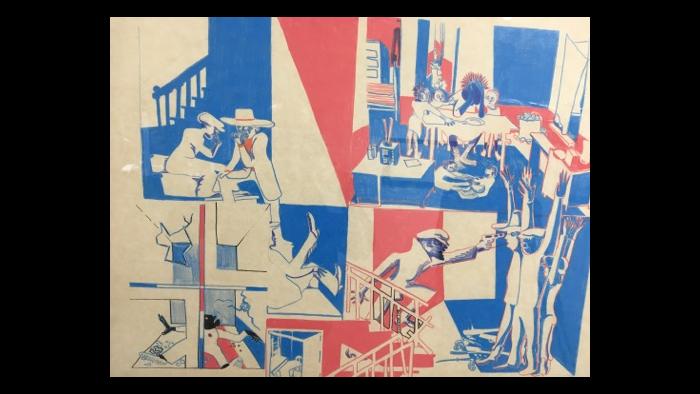

The third one is called “Red White and Blue, I Love You.” So you see some of the same issues of drug addiction, violence, that we see in the other series, but they’re all rendered in red, white and blue, so it’s sort of giving this polite nod to say, “Hey this country is having a lot of problems, but I’m still a patriot. I served my country, and I still love this country so we’re trying to hold out a little hope.”

But again continuing to show the world and showing people, “Hey this is not right. We need to take steps to changing it. The first step in getting dirty laundry clean is to bring it out of the hamper and bring it into the air and the light.”

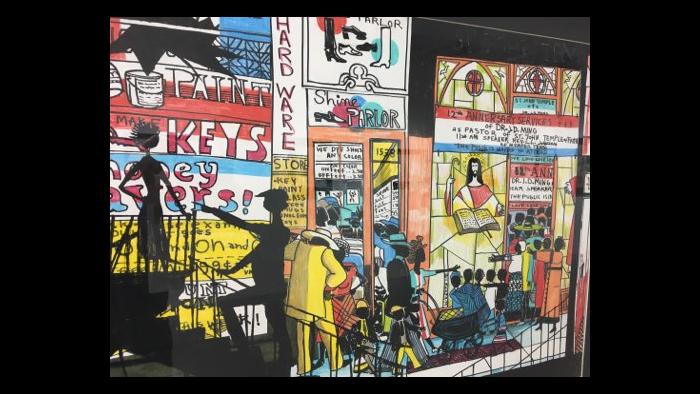

Ponce: Walker made a name for himself in public art.

He was the driving force behind the historic mural, the Wall of Respect, which debuted in 1967 at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue.

Hawkins: The idea was one, to bring beauty into a really rough neighborhood. Some people called that neighborhood “the bucket of blood” because of gang violence and poverty, and so it was about bringing beauty, but it was also a sense of history. Part of the impetus was to show the community, to show its children all of this wonderful black energy and black pride.

Ponce: The curator of this exhibition had a personal connection to the wall.

Hawkins: My mother, Florence Hawkins, was one of the painters of the Wall of Respect. She was a member of the community. We lived right around the corner on Champlain. And so oftentimes he welcomed people from the community. He was known for interacting with people in the neighborhoods that he worked in, and my mother just saying, “Oh you guys are painting something, this looks cool, I’m an artist, can I play?” and they gave her a brush.

Ponce: Much of the work in the exhibition comes from Chicago State University. Unlike his usual canvas of brick and concrete, Walker created these on paper, newspaper, even Plexiglas.

Hawkins: He felt that truth—and as an artist speaking the truth—that was one way of helping mankind sort of stave off his own destruction … in terms of just saying, “Hey we’re not gonna pull back, because this is the reality that many of us are dealing with.”

So as such we can’t afford to just be inured to what’s around us, just because it seems to be a way of life. We have to rise up, we have to collaborate, we have to cooperate and make positive change.

Note: This story originally aired on “Chicago Tonight” on Nov. 15.

Related stories:

‘Race’ Exhibition Challenges Visitors to Rethink the Concept

‘Race’ Exhibition Challenges Visitors to Rethink the Concept

Nov. 13: What does race mean to you? A new exhibit at the Chicago History Museum asks visitors to consider how much all of us focus on race every day, whether we realize it or not.

Hebru Brantley’s New Art Show Takes Flight in Elmhurst

Hebru Brantley’s New Art Show Takes Flight in Elmhurst

Sept. 20: His artwork is in the collections of George Lucas, Jay-Z and Mayor Rahm Emanuel. We get a preview of the show “Hebru Brantley: Forced Field” at the Elmhurst Art Museum.

Monumental Exhibitions Open Doors to Chicago History

Monumental Exhibitions Open Doors to Chicago History

March 2: Two new shows at the Chicago Cultural Center open doors to a local arts movement from 50 years ago.