In this encore edition of Ask Geoffrey, our local history expert Geoffrey Baer digs deep into the history of Montrose Beach, revisits a Streeterville puppet show and examines underground architecture on the Blue Line.

Whatever happened to the Kungsholm puppet theater on Michigan Avenue?

–Jon Jenkoover

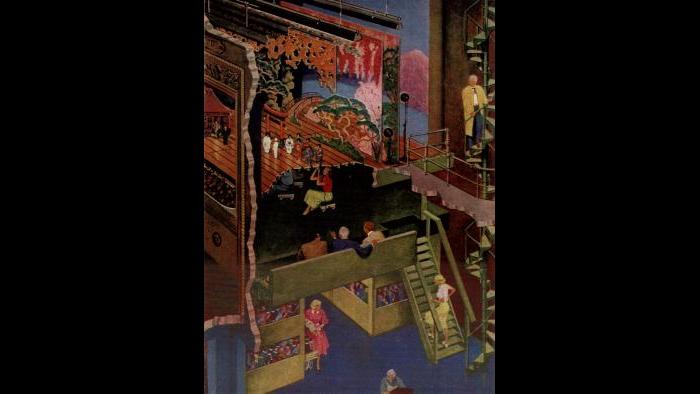

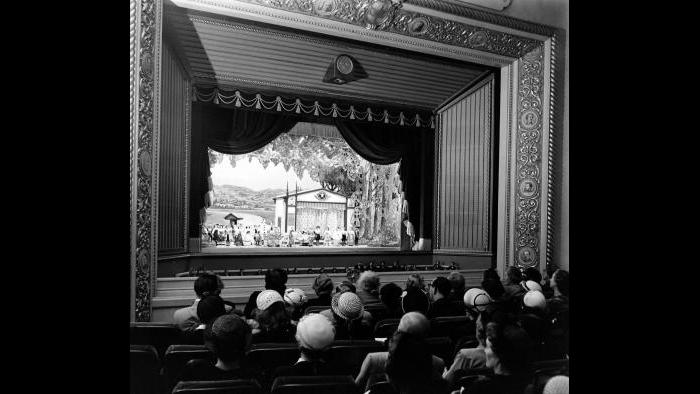

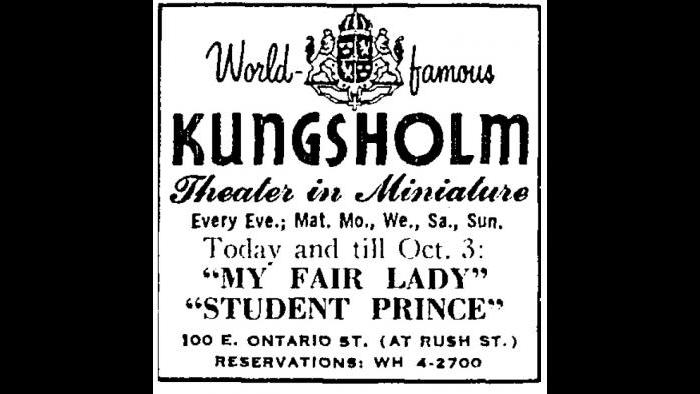

The Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera staged elaborate puppet operas at a restaurant a little bit west of Michigan Avenue at Rush and Ontario streets from 1937 to 1971. The restaurant was in a mansion originally built as the home of a member of the McCormick family, but the idea of the extravagantly-staged puppet operas actually predates the restaurant.

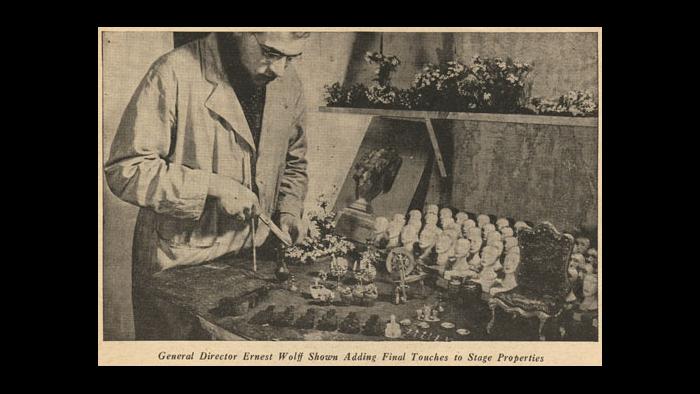

It started with a young Chicagoan named Ernest Wolff, who created intricate opera sets in miniature as a teenager. In 1936 (a year before Kungsholm restaurant opened), Wolff and his mother founded the Chicago Miniature Opera Company and soon Wolff was touring the country with his pint-sized puppet versions of famous operas. Then in 1940, Wolff put his opera business on hold to serve in World War II.

The restaurant’s owner Frederick Chramer had seen one of Wolff’s performances. With Wolff’s permission, he turned the ballroom of the Kungsholm restaurant into the Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera. But while Wolff was serving in the war, Chramer started taking credit for inventing the puppet opera. When Wolff returned from military service, he sued Chramer for stealing his idea – and won.

Even after losing the suit, Chramer was able to continue the opera, but eventually his health started failing and he sold the restaurant and the show to the Fred Harvey chain in 1957. According to Kungsholm puppeteer Bill Fosser’s history of Kungsholm, that was the beginning of the end. The new owners didn’t keep up the production quality and the crowds stopped coming. The Kungsholm puppet opera closed its curtains for good in 1971.

Bill Fosser, who died in 2006, carried on the art of puppet opera with his own company called Opera in Focus. That company continues to put on lavish puppet operas at the Rolling Meadows Park District Theater. In 2011, Jay Shefsky profiled the company. See his story below.

Why are the Belmont and Logan Square Blue Line stations so aesthetically different from all other subway stations?

–Jayne Blacker

Belmont Station

The short answer is that all CTA stations reflect the architectural style of the era in which they were built. For decades, the Logan Square station was elevated above ground, rather than being a subway stop. In fact, it was the last stop heading out of the Loop on the West-Northwest Route, or what’s now known as the Blue Line.

Belmont Station

The short answer is that all CTA stations reflect the architectural style of the era in which they were built. For decades, the Logan Square station was elevated above ground, rather than being a subway stop. In fact, it was the last stop heading out of the Loop on the West-Northwest Route, or what’s now known as the Blue Line.

In 1965, Mayor Richard J. Daley proposed a massive wave of improvements and additions to Chicago’s transportation system. One of those was to extend the West-Northwest Route to a new terminus at Jefferson Park with stations running down the median of the Kennedy Expressway.

The extension opened in 1970. In order to get into the middle of the expressway, the first part of the extension was routed through a newly built tunnel and the Logan Square stop became a subway station. A new subway station was also added at Belmont.

The Chicago architecture firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill designed the two underground stations in the boxy International Style the firm became famous for. The stations were designed to accommodate the sleek new stainless steel 2200-series railcars rolled out that year. Like the 2200-series cars, the stations themselves featured lots of shiny stainless steel, like in these agents’ booths.

(David Wilson)

(David Wilson)

These days, the ticket booths, entry turnstiles and Ventra machines are located on cantilevered platforms on a mezzanine level overlooking the stations’ track levels. Down at track level, the stations are lit by lights recessed into coffered ceilings. Toward the center of each station, the ceiling curves into an arch that echoes the 2200-series railcar’s roofline. All of this might remind people of Washington, D.C.’s famous Metro system designed by Chicago architect Harry Weese, which opened just a few years later. But we found no evidence either design influenced the other.

Above ground, the subway entrances and the stations in the highway median are simple, rectilinear steel-and-glass structures again reflecting SOMs modernist style.

As is so often the case for questions about the "L," we found much of this information at Graham Garfield’s wonderful website Chicago-l.org.

The Montrose Beach area is a hidden gem with so much to explore. What is the history of the pier which extends into the lake at the east end of the beach?

The Montrose Beach area is a hidden gem with so much to explore. What is the history of the pier which extends into the lake at the east end of the beach?

–Judy Corbeille

The Montrose Beach we know today didn’t exist until the early 1930s. It’s built entirely on manmade land along with almost all of Lincoln Park east of Lake Shore Drive. This was part of the vision of Daniel Burnham, whose 1909 Plan of Chicago conceived our lakefront park system. Even before the Burnham Plan there had been efforts to reinforce the eroding lakefront with stone rubble and timber structures called revetments. Filling progressed over the decades northward from North Avenue. By the time construction began at Montrose around 1930, the technology switched to sheet metal pilings. After this, dirt and other fill material was added behind the sheet metal to create the land that is now the park and sand was added on the lakefront to form the beach.

Wave action in the lake would have soon washed away that beach were it not for the structure our viewer called a pier. It’s actually called a groin. There are groins all along the lakefront that project in a north-northeast direction out into the lake. That’s because north-northeast is the typical direction for wave action from storms in Lake Michigan. The groins trap beach sand moved by this wave action, creating beaches on their north sides.

But that’s not all there is to see at Montrose Beach. The beach house at Montrose is designed to look like a lake steamship. It’s modeled on the one at North Avenue, although part of it burned and was never rebuilt. And, a new Lake Michigan dune has been forming at Montrose for the last several years. It began when workers failed to groom the beach one season and has been encouraged since then by volunteers who plant dune grass and keep people from trampling the sand.

A final historical note: in 1954, Montrose Beach was hit by a freak wave, more accurately called a seiche. Seiches are standing waves oscillating in enclosed bodies of water like lakes. (Think of the way water sloshes back and forth in a bathtub. The lake is like a really, really big bathtub and if water goes down on one side it rises up on the other.) The 1954 seiche was the biggest ever and Montrose Beach got the worst of it. Fifty fishermen on the pier were swept into the water. Most were rescued, but eight people drowned at Montrose and North Avenue Beaches that day.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.