Chinese Madonna scroll at the Field Museum (Chloe Riley)

Chinese Madonna scroll at the Field Museum (Chloe Riley)

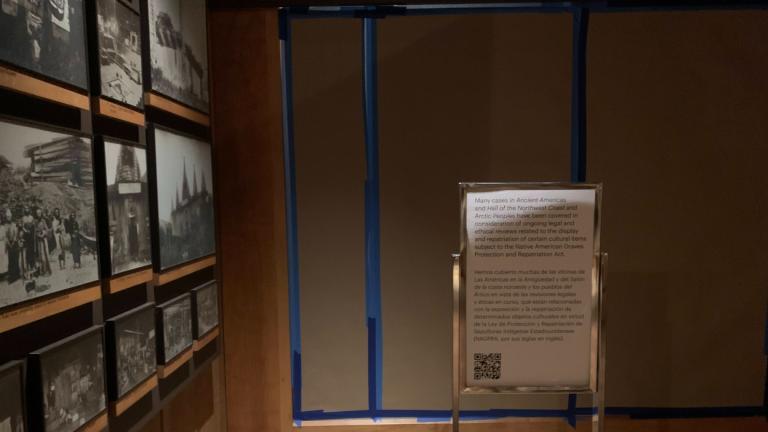

We’re standing in front of a door that looks like it could be made for Andre the Giant. This is in the Field’s anthropology section, which, like most of the museum, consists of a series of doors, closets and winding hallways so intricate that even my guide – who’s already been here for several months – sometimes gets lost.

The “we” consists of a small group from the museum and myself. We’re here, pondering the largeness of the door, because we’re waiting on one last person to aid in the unveiling of a scroll so fragile it rarely leaves its wooden box within the anthropology department where it normally lives.

The door’s so big, explains Gary Feinman, the Field’s curator of – among other things – East Asian anthropology, because the anthropology department used to make its own exhibits back in the day. They don’t do that anymore.

The reason any of us are standing here at all has to do with another curator of Asian anthropology, a man by the name of Berthold Laufer, who held that role at the Field from 1908 to 1934. More than three-quarters of the museum’s current Chinese anthropological collection comes from Laufer, who, during his tenure at the Field, collected more than 19,000 objects from China and Japan.

One of those objects, acquired in 1910, is a Chinese scroll depicting Madonna holding Jesus as a child. Rolled out to its fullest, the paint-on-silk scroll stretches 8 feet long and is thought to be modeled after the Salus Populi Romani – a Byzantine image of the Madonna and child which some scholars date to as early as the 5th century.

Like many captivating things, an element of mystery surrounds this scroll, which is stamped with the mark of Tang Yin – one of China’s most famous painters who lived and worked through the 15th and 16th centuries. But Laufer was convinced the Tang Yin seal was a forgery added almost a century later in an effort to protect the painting during a period when both Christianity and Christian iconography were being suppressed in China, according to Deborah Bekken, who co-curated the Field’s new Cyrus Tang Hall of China.

“What happened is that probably a copy of this earlier Roman image somehow made it to China with a group of Christians – could have been Franciscan missionaries. Could have been as late as the Jesuit mission, although probably it came in a little bit earlier,” Bekken says.

But, according to Feinman, some scholars believe that Tang Yin may actually have painted the scroll, which would put it closer to 15th century instead of Laufer’s original 17th century estimation.

“That’s what Laufer thought, but recent scholars now think that – no, the painting is actually earlier and was done with very early Christian influences in China,” says Feinman.

Though debate still lingers over the when and who of the scroll, its subject matter – and the art with which it was crafted – seem to be a point of reverence, especially among the 15 or so Field pilgrims who’ve come today to catch a glimpse of the painting before it’s rolled back into obscurity.

Aside from the occasional technical murmurings from its handlers, there’s almost total silence as the scroll makes its way back into the light. Like some ancient Egyptian ritual, boxes are removed, wrappings untwined, until finally two bodies come forth. The first, a Mary with almond-shaped eyes, carries the second, a Jesus draped in red, his head tufted with dark hair.

Unrolling of the Field Museum's Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

Unrolling of the Field Museum's Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

The last time the scroll emerged from its home in anthropology was 2007, when it was restored and then taken on a mini tour, first to Virginia for the 400th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement, then on to the Vatican. This time, the scroll is unveiled for "Chicago Tonight" and also so the museum can take video of the painting for archival purposes.

Feinman and Bekken stand over the scroll, two proud smiling parents.

Feinman: “It’s somebody’s version of what the Madonna and child looked like. It’s not a historical representation, but it’s a translation of the story. It’s always stunning because it’s such a remarkable piece and it’s so clearly a kind of influence between cultures and when you think about that and the fact that it’s hundreds of years old and the meaning that it has, it’s sort of overwhelming.”

Unrolling of the Field Museum's Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

Unrolling of the Field Museum's Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

Bekken: “It’s a beautiful image. The somber colors, the very fine detailing. It’s just a really beautiful image.”

Feinman: “It’s just an incredible composition too. The way the color is injected in just a few spots, the child is sort of draped in red and then you have the red framing of his head,” he says, pointing to the boy Jesus.

Bekken: “Yeah, and the halo is a little more transparent behind her head, whereas the robe is more saturated, looking more like fabric. His book (she points to Jesus) his little book of gospels is obviously in the Chinese style – they have books that are bound to be read from right to left, so you’re seeing the front cover of the book there.”

The Field's Deborah Bekken points out a detail on the Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

The Field's Deborah Bekken points out a detail on the Chinese Madonna scroll (Chloe Riley)

Feinman: Oh yeah.

Bekken: As opposed to left to right the way that we do. (pauses) It’s just a really lovely image.

Feinman: We don’t get to see it very often, (laughs).

Bekken: Literally, this is the second time I’ve seen it and I’ve worked here for 18 years (she laughs too).

The Field's Deborah Bekken (left) and Gary Feinman stand over a rarely unveiled Chinese scroll. (Chloe Riley)

The Field's Deborah Bekken (left) and Gary Feinman stand over a rarely unveiled Chinese scroll. (Chloe Riley)

Nervous laughter subsides, photos get taken for social media, and our pilgrims begin to shuffle anxiously, suddenly remembering the museum’s millions of other bodies in need of tending. And then finally, in its own kind of little resurrection, the scroll gets rolled back up, strings tied, vault resealed. Until another unveiling, some other time.

More from this "Chicago Tonight" series:

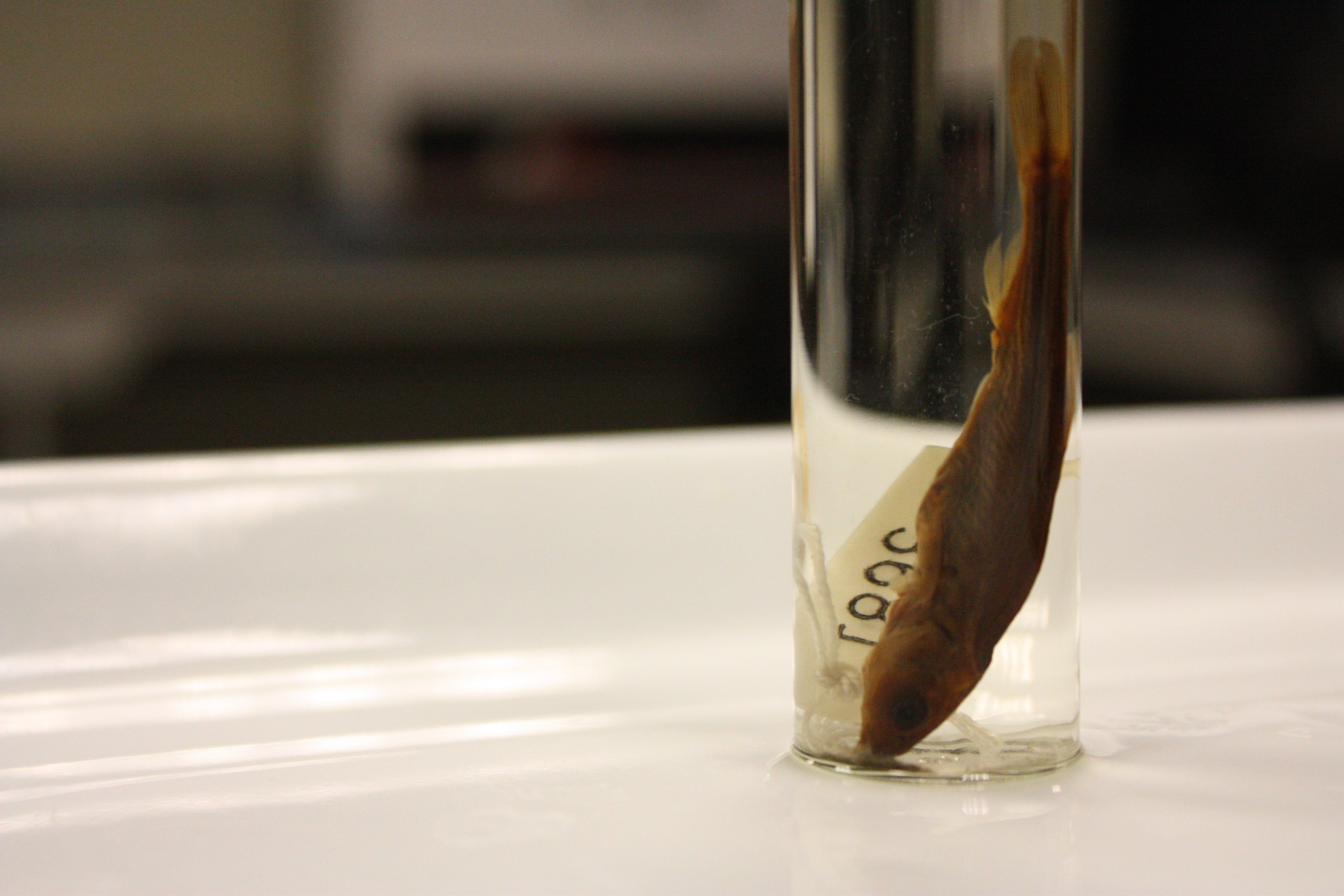

Fish at Field Museum is Only One of its Kind in Existence

Fish at Field Museum is Only One of its Kind in Existence

At first glance, the small, formaldehyde-soaked Evarra tlahuacensis doesn’t come off as a terribly striking fish. But the little minnow is actually the only remaining specimen of its kind on Earth.

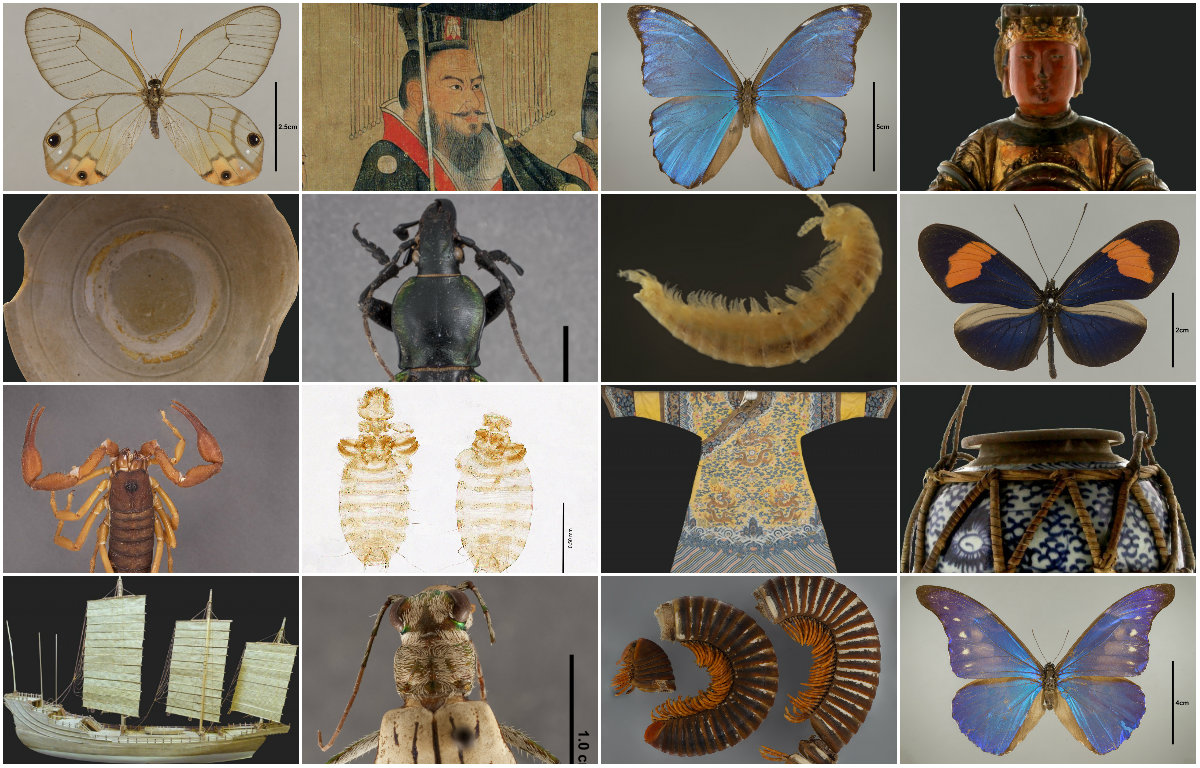

Field Museum Rediscovers Beetle First Collected by Charles Darwin

Field Museum Rediscovers Beetle First Collected by Charles Darwin

A beetle collected by Charles Darwin was recently discovered at the Field, which is in the process of cataloging its 12 million insect specimens – the museum's largest collection.

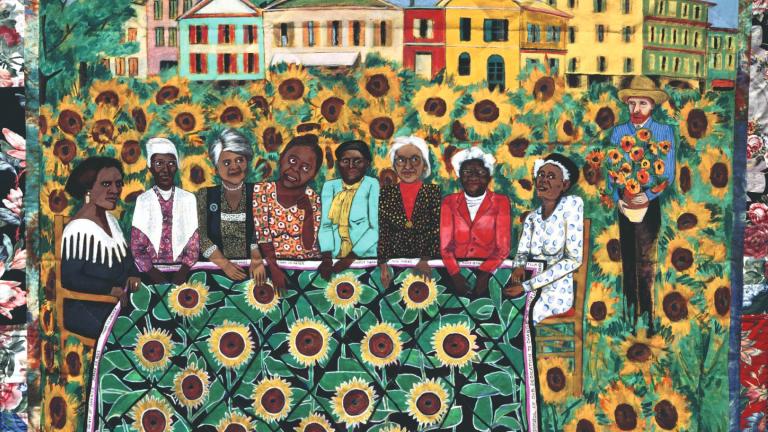

Field Museum Digitizes a Fraction of Its Nearly 30 Million Specimens

Field Museum Digitizes a Fraction of Its Nearly 30 Million Specimens

More images are now available on the museum’s website, but exactly what good are they to the public?