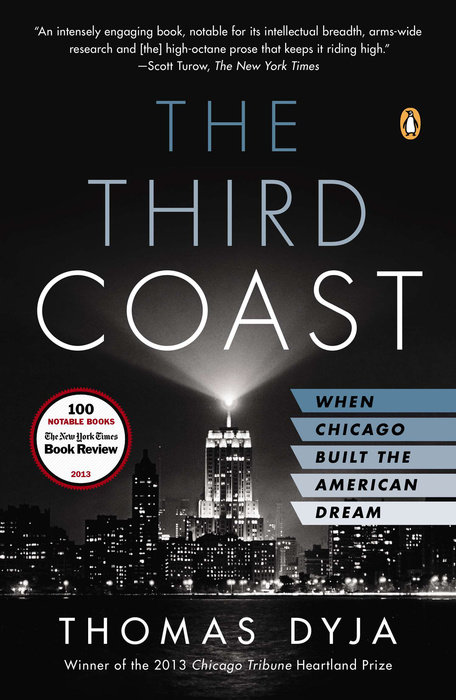

Thomas Dyja's sweeping history of his hometown, subtitled "When Chicago Built the American Dream," is the newest One Book, One Chicago selection.

The book covers a wide cast of characters inhabiting post-WWII Chicago–everyone from Mahalia Jackson to Mies van der Rohe, from Hugh Hefner to Howlin' Wolf. Dyja balances deeply personal portraits with in-depth research into how Chicago helped shape midcentury America.

The author joins "Chicago Tonight" on Tuesday for a conversation. Get information on his appearance Wednesday at Harold Washington Library.

Below, some highlights from our conversation.

On the role the public library played in his life:

"Enormous. My mother used to always drag me off to the Belmont-Cragin branch. I spent many hours literally going along the shelf, from book to book. It really was the kind of door pre-Internet; that was really the place that launched me, so having the library be involved in this, and picking me, really is kind of closing the circle."

On his literary heroes, growing up as a Northwest Side kid:

"Sure. Hemingway–you had to. I grew up not too far from Oak Park. [Carl] Sandburg: loved Sandburg. I remember being in high school (and cutting school) and going and sitting on the lakefront and reading Sandburg and saying, 'You know, I think I'd like to be a writer.' It's jaw-dropping to have it kind of come around that way.

"I loved [Nelson] Algren, I always have; and Terkel–Studs was always reading that was a great education in thinking about people. That sense of having this book be about the people from that period really came from those writers who were so about the people around them."

On what made Chicago a cultural powerhouse from 1945-1960:

"Some of it is just geography. Chicago was in the center of America, so it was the capital of Manifest Destiny. There was a period when, if you were taking a train across America, you literally had to stop in Chicago and switch trains. In 1960, you get the first transcontinental jet flights and suddenly, everybody can fly over Chicago. It was more than just metaphorical. But there was a time when everybody had to take Chicago in. It really was the center place of America. It was Vegas before there was Vegas."

Some more of the cultural highlights featured in "The Third Coast":

Below, the preface from the book.

THE THIRD COAST by Thomas Dyja - preface

Under the light of a single bulb, the old drunk slipped into a coma. Louis Sullivan, the greatest architect in a city of great architecture, lay dying of kidney disease at the Warner Hotel on 33rd and Cottage Grove, five years after the White Sox had met there to fix the 1919 World Series. His last designs had been a series of extravagant little banks in midwestern hamlets, jewel boxes cascading with his glorious ornament, but they’d paid nothing, so old friends like his former protégé Frank Lloyd Wright had chipped in for this dingy room. As the bulb swung and his breathing shallowed, Chicagoans went on shopping in his department stores, cooking dinner in his homes, shuffling papers in his offices, dozing off in his theaters, and praying in the churches he’d created. Few had any clue how Sullivan had given form to the functions of their lives.

He’d come to Chicago in 1873, chased west by the year’s financial panic to a city whose purpose was to be in the middle. Before Marquette and Joliet came through in the late 1600s, centuries of Potawatomi Indians had portaged here between Lake Michigan and the Des Plaines River, paddling on to the Mississippi. French fur traders set up shop in the 1700s, and as the railroads pushed west in the next century, the frontier outpost named Fort Dearborn grew into Chicago, hub of the expanding nation. From every direction, people, resources, and products moved through its muddy plains, soon the site of the world’s biggest, wildest boomtown, and when the fire of 1871 scoured most of the city away, America willed it back into existence, this time even bigger and wilder. Between 1870 and 1890, the city’s population grew from just under 300,000 to more than a million souls densely packed and separate, every person there to do, to make, to somehow get theirs. Grain and livestock mattered as much as pig iron; labor confronted capital; new sciences were explored amid back-alley violence. “Having seen it, I urgently desire never to see it again,” said an uncharacteristically prim Rudyard Kipling after an 1890 visit. “It is inhabited by savages.” Historian William Cronon has called it “the grandest, most spectacular country fair the world has ever seen.” You could probably find fifty just like it now in China, but Chicago was the first of its kind, and Louis Sullivan had loved it at first sight. “Here . . . was power,” he wrote, “naked power, naked as the prairies, greater than the mountains.”

After a short stint at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Sullivan teamed up with Dankmar Adler to design scores of buildings that expressed the extremes of the city that gave America its meat, steel, and the Wizard of Oz. Together Sullivan and Adler refined the idea of what a skyscraper should be. They pushed the limits of technology in buildings such as the Auditorium and the Schiller Theater, while Sullivan developed his distinctive ornamentation, an intricate, organic system that wound around the straight lines of modern industry, exploring the aesthetic possibilities of a grain of wheat the way Bach explored music. Sullivan’s florid yet rational ornament mediated between Chicagoans and their buildings. It captured the creative tension between rural and urban, past and present, the individual man and the democratic nation that fueled the city. Sullivan gave form to the idea of Chicago as a crossroads, where all of America’s impulses met to converse and trade, battle and build, each structure a message about how technology and man could thrive together. The Columbian Exposition of 1893 ended all that, though. Grand as Daniel Burnham’s fair was, it pushed the first generation of Chicago skyscraper builders out of fashion, and the city’s progress stumbled. Adler and Sullivan split, and as Sullivan took to the bottle, he warned— or cursed— that it would be fifty years before American architecture recovered. He was off by only five or so.

When Sullivan died that night in 1924, he died forgotten. Chicago was no longer his city, as much as it ever had been. In the 1920s virtually everyone went on the take— not just Al Capone but union bosses and corporate heads, aldermen and corner cops; even a few priests were mobsters under the Roman collar. Five years later the stock market crash would drag the city to the brink of collapse.

Out of those ashes, Chicago did rise again. It was a slow, often painful progress infused with creativity and greed, overshadowed by the two glamorous cities on the other coasts, but central in all ways to the massmarket America we know today. Beginning in the late 1930s and rolling on through the 1950s, Chicagoans produced much of what the world now calls “American”: the liberated, leering sexuality of Playboy; glass and steel modern architecture; rock and roll and the urban blues; McDonald’s and the spread of the fast-food nation; the improvisational sketch comedy that’s trained everyone from Joan Rivers and John Belushi to Steve Carell and Tina Fey; Ebony magazine and Emmett Till, whose murder catalyzed the civil rights movement; geodesic domes; avant-garde jazz and gospel music; the Nation of Islam; modern photography; the atom bomb and the Great Books; Kukla, Fran and Ollie; and the last great political machine.

The Third Coast is the history of Chicago’s greatest— and final— period as the nation’s primary meeting place, market, workshop, and lab, but it is also the story of how America’s uniform culture came to be. As New York positioned itself on the global stage and Hollywood polished the nation’s fantasies, the most profound aspects of American modernity grew up out of the flat, prairie land next to Lake Michigan. The real struggle for America’s future— whether it would be directed by its people or its institutions— took place in postwar Chicago.

Reprinted from The Third Coast by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House, Inc. Thomas Dyja © 2013.

Northwest Side native Thomas Dyja discusses "The Third Coast" and this year's One Book, One Chicago theme on Wednesday at the Harold Washington Library Center. The free event is open to the public and takes place from 6-8 p.m. Seating is available on a first-come, first-served basis in the Cindy Pritzker auditorium and will be limited to 385. Books will be available for purchase and Dyja will sign books at the end of the program. Click here for more information.