In this edition of Ask Geoffrey, our local history expert goes ringside at Joe Louis' first professional knockout, rides by the site of long-lost Logan Square mansion, and finds out what's cooking at a former bread-baking palace.

Heavyweight boxer Joe Louis

In 1934, boxer Joe Louis won his first pro match at Bacon's Arena in Chicago. Where was Bacon's Arena located? I couldn't find anything about it online. I'm guessing the arena is long gone.

Heavyweight boxer Joe Louis

In 1934, boxer Joe Louis won his first pro match at Bacon's Arena in Chicago. Where was Bacon's Arena located? I couldn't find anything about it online. I'm guessing the arena is long gone.

–Biart Williams, Frankfort

The heavyweight great Joe Louis did indeed win his first professional fight at Bacon’s Arena on the evening of July 4, 1934, defeating former University of Illinois student Jack Kracken in six rounds. Bacon’s Arena, also known as Bacon’s Casino, was an arena and dance hall located in the Bronzeville neighborhood at 4859 S. Wabash (the building is in fact gone now.). The Chicago Tribune described the fight as ending when Louis hit Kracken on the jaw with a left hook and the Champaign heavyweight went down for a nine count; then Louis closed in and knocked his opponent through the rope and into the lap of Joe Triner, chairman of the Illinois athletic commission, with a straight right. Kracken climbed into the ring at the count of 14, at which time the referee stopped the fight. The fight was attended by 1,133 spectators and Louis was paid $59 in prize money for the win. Seven days later Louis KO’d Willie Davis for $62, also at Bacon’s. For his next fight he was in Marigold Gardens for $101. Louis fought three more fights in Chicago before returning to his hometown of Detroit.

Bacon’s Casino was a dance hall that opened in 1928. The proprietors were two dance instructors and brothers Robert and Ernest Bacon, who had come to Chicago during the Great Migration of African-Americans from the Deep South. According to the Chicago Tribune, the hall was large enough for 800 dancing couples and featured two large fountains in the center of the dance floor.

Photos of the building’s exterior have been difficult to locate, but the Bronzeville Historical Society’s Thomas Tracy sent us this photo taken in front of Bacon’s in 1937. Tracy’s grandmother, Rosa Belle Hayes Lee, was a past matron of this chapter of a fraternal order called the Order of the Eastern Star.

In 1949, Bacon’s became a union headquarters for the United Packinghouse Workers of America. A few years later the UPWA demolished Bacon’s Casino and constructed a new building on the site. The UPWA later merged with another union and moved out. Today the building is home to the Charles A. Hayes Family Investment Center, which runs a health care center, early childhood education programs, library, and parent training classes for public housing residents.

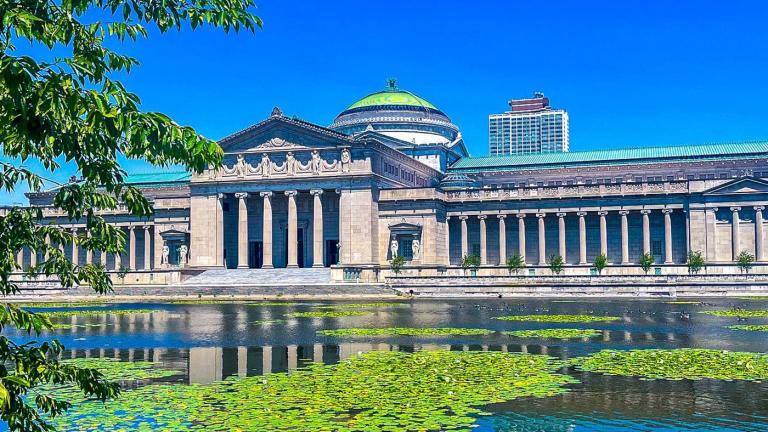

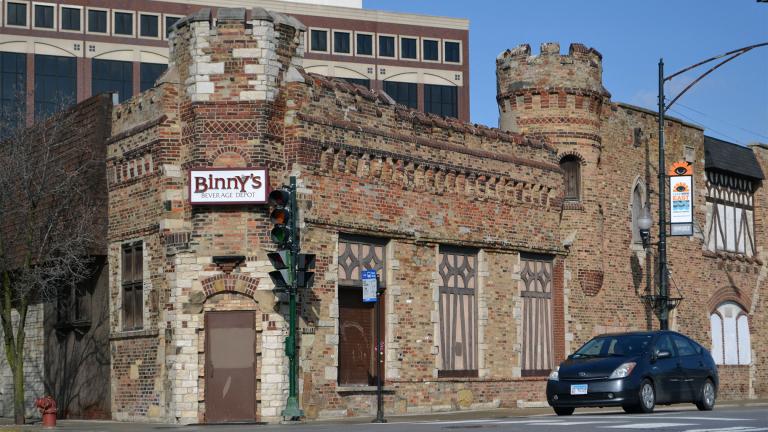

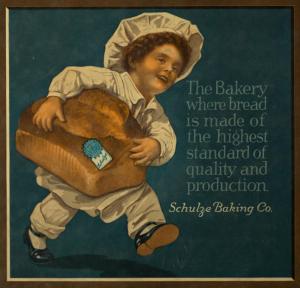

I recently noticed a beautiful building on the corner of Wabash and 55th with lovely ornament and ornate seals near the top. It says "Schulze Baking Company" on it, but it looks boarded up. Can you tell me more about why a baking factory looks so beautiful and what's still going on in there?

–Michael Lipkin, Hyde Park

For 90 years, Butternut bread was baked at the stunning Schulze Baking Company in the Washington Park neighborhood until 2004. Completed in 1914 and designed by John Ahlschlager, the Schulze Baking Company plant was one of the most advanced industrial buildings of its time.

For 90 years, Butternut bread was baked at the stunning Schulze Baking Company in the Washington Park neighborhood until 2004. Completed in 1914 and designed by John Ahlschlager, the Schulze Baking Company plant was one of the most advanced industrial buildings of its time.

Schulze Baking Company owner Paul Schulze saw his factory as the solution to a public health problem. He told the American Bakers’ Association that American housewives were killing their husbands with their home-baked bread because their ovens could not get hot enough to cook bread through, leaving the center raw. Schulze hoped to end the scourge of these death loaves with his fine products—and he baked them in a factory that looked nothing like other industrial buildings of its time because Schulze sought to distinguish his plant from those standard red-brick factories. According to the National Register of Historic Places, he envisioned a beautiful bread-baking palace as a symbol of operational efficiency and cleanliness. So Ahlschlager designed an airy factory ringed with windows, clad in white-glazed brick and lavished with white terra cotta ornament. Inside, an assembly line, heavy load bearing floors, high ceilings and conveyor ovens made it a technological marvel in the baking industry.

After suffering a head injury, Schulze retired only seven years after building his bread palace. Two subsequent owners, Interstate Bakeries and Lewis Bakeries, continued to make Butternut Bread there until the factory closed in 2004. The owner blamed America’s shift to healthier whole wheat bread for the loss of the business. The building has been vacant since then, but plans are in place to convert it to a high-tech data center by developers 55th and State working with architects Pappageorge Haymes.

But the Schulze name is not gone from Chicago baking. In the 1930s, Schulze and his son Paul Jr. formed another baking company, the Paul Schulze Biscuit Company, which produced saltines and troop rations. It’s now known as Schulze and Burch, and makes toaster pastries and granola bars in a plant in the Bridgeport neighborhood. In the video below, take your taste buds on a walk down memory lane with this 1967 commercial for Toast’em Pop-Ups.

A friend was telling me of growing up with the "Schwinn boys" of bicycle fame. The house was on Sacramento Street, and "Pop" Schwinn had an electric elevator for his selection of cars (or was it a roundtable?). Is this home and garage still in existence?

–Nancy Fagin, West Town

The Schwinn brothers, Frank V. and Edward R. Schwinn, did live at Palmer and Sacramento overlooking Palmer Square in a grand 15-room mansion with their father Frank W. and grandfather Ignaz “Pop” Schwinn, who founded the Schwinn Bicycle Company. And according to the book about the Schwinn company’s history, No Hands, the garage had not an elevator but a turntable so Ignaz could turn his car around without having to back it out onto the street.

The Schwinn brothers, Frank V. and Edward R. Schwinn, did live at Palmer and Sacramento overlooking Palmer Square in a grand 15-room mansion with their father Frank W. and grandfather Ignaz “Pop” Schwinn, who founded the Schwinn Bicycle Company. And according to the book about the Schwinn company’s history, No Hands, the garage had not an elevator but a turntable so Ignaz could turn his car around without having to back it out onto the street.

Ignaz founded the Schwinn Bicycle Company in 1895, with his partner Adolph Arnold. In 1901, Arnold, Schwinn and Company, as it was then called, built a factory in the nearby Hermosa neighborhood. Schwinn bought out his partner in 1908 and the new Schwinn Bicycle Company quickly became one of the leading firms in the industry renowned for their quality bicycles. Ignaz steered the company through bike boom and bust cycles during the early part of the century until his son Frank W. took over the company in the 1920s.

Ignaz cycled on to the next great ride in 1945, and his son Frank W. donated the house and land to the nearby St. Sylvester Church about a decade later. The church razed the mansion and built a school in its place. The combined cafeteria and auditorium is named Schwinn Hall.

While the mansion is long gone, a building Ignaz built right across the street survives. He built the Shakespeare Apartments in 1907 for company employees. Andrew Schneider of Logan Square Preservation told us that neighborhood lore is the canny Ignaz built it to keep an eye on the workers’ comings and goings.

Schwinn produced its last bike in Chicago in 1982, shifting production to its plant in Greenville, Miss. The corporate headquarters moved to Colorado the following year. Nine years later the company entered bankruptcy and the brand was purchased by an investment group. Schwinn bikes can still be found at department stores, but they’re made overseas.

More Ask Geoffrey:

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city's past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.