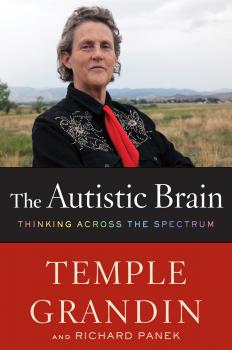

A well-known adult with autism and one of the world’s most prominent speakers on the subject visited Chicago to speak at the Chicago Humanities Festival this past weekend. Temple Grandin is a best-selling author, professor of animal science at Colorado State University, and also has an HBO movie based on her life starring Claire Danes which won seven Emmy Awards. Grandin analyzed animal behavior and created a livestock handling facility that encourages the humane treatment of animals before slaughter. Recently, autism itself has become the subject of her work. Grandin’s most recent book, The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum provides a perspective into the autistic brain from her own experiences and she shares the latest scientific research on causes and treatments. She joins us to discuss her book and more. Read an excerpt below.

Excerpt from The Autistic Brain by Temple Grandin

I’m certainly not saying we should lose sight of the need to work on deficits. But as we’ve seen, the focus on deficits is so intense and so automatic that people lose sight of the strengths. Just yesterday I spoke to the director of a school for autistic children, and she mentioned that the school tries to match a student’s strengths with internship or employment opportunities in the neighborhood. But when I asked her how they identified the strengths, she immediately started talking about how they helped students overcome social deficits. If even the experts can’t stop thinking about what’s wrong instead of what could be better, how can anyone expect the families who are dealing with autism on a daily basis to think any differently?

I’m concerned when ten-year-olds introduce themselves to me and all they want to talk about is “my Asperger’s” or “my autism.” I’d rather hear about “my science project” or “my history book” or “what I want to be when I grow up.” I want to hear about their interests, their strengths, their hopes. I want them to have the same advantages and opportunities in education and the marketplace that I did.

I find the same inability to think about children’s strengths in their parents. I’ll say, “What does your kid like? What is your kid good at?” and I can see the confusion in their faces. Like? Good at? My Timmy?

I have a routine I follow in these cases. What’s your child’s favorite subject? Does he have any hobbies? Does she have anything she’s done—artwork, crafts, anything—that she can show me? Sometimes it takes a while before parents realize that their kid actually has a talent or an interest. Two parents came up to me recently and said they were concerned because they knew their son wouldn’t be able to handle the family business, a ranch. What would become of him, since that was the only world he’d ever known? Well, yes, it might be the only world he’d ever known, but the kid wasn’t nonverbal. Their kid could function. So what part of that world interested him? Fifteen minutes later, they finally said that their son liked fishing.

“So maybe he can be a fishing guide,” I said.

I could almost see the light bulbs popping to life above their heads. They now had a way to rethink the problem. Instead of thinking only about accommodating their son’s deficits, they could think about his interests, his abilities, his strengths.

Watch a web extra video of Grandin discussing her appearance at the Chicago Humanities Festival: