A city of Chicago outfall at the Wild Mile floating wetland installation on the North Branch of the Chicago River. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A city of Chicago outfall at the Wild Mile floating wetland installation on the North Branch of the Chicago River. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Hundreds of people are expected to take part in an open water swim in the Chicago River in September — the first such event in nearly a century, organizers say — that is, if the water quality cooperates.

New, more stringent requirements regarding the city of Chicago’s sewer discharges into the river system could make the swim likelier to occur than not.

At the beginning of April, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency issued a new permit to Chicago — effective through February 2029 — governing the city’s 184 sewer outfalls. These are the places where the sewer system connects to the river system.

Though wastewater — sewage, stormwater, industrial waste, etc. — is nearly always diverted to a treatment plant before being discharged into waterways, occasionally the system is overwhelmed and pollutants are flushed directly into the river, in what’s known as a combined sewer overflow (CSO).

“All of a sudden there’s a glut of trash and debris, everything people have put down their drains — plus all the nasty chemicals that come with being in an urban environment — are all washed in at once. It often comes with especially turbid waters and generally a smell that is less than pleasant,” said Phil Nicodemus, director of research at Urban Rivers, describing discharges at the organization’s floating wetland installations at Goose Island and Bubbly Creek.

“We know that influxes of untreated discharge affect the river ecosystem from the bottom up, and it takes several days to recover, and the pollutants and extra organic material washed in may take decades to be digested, filtered or carried away, if ever,” Nicodemus continued.

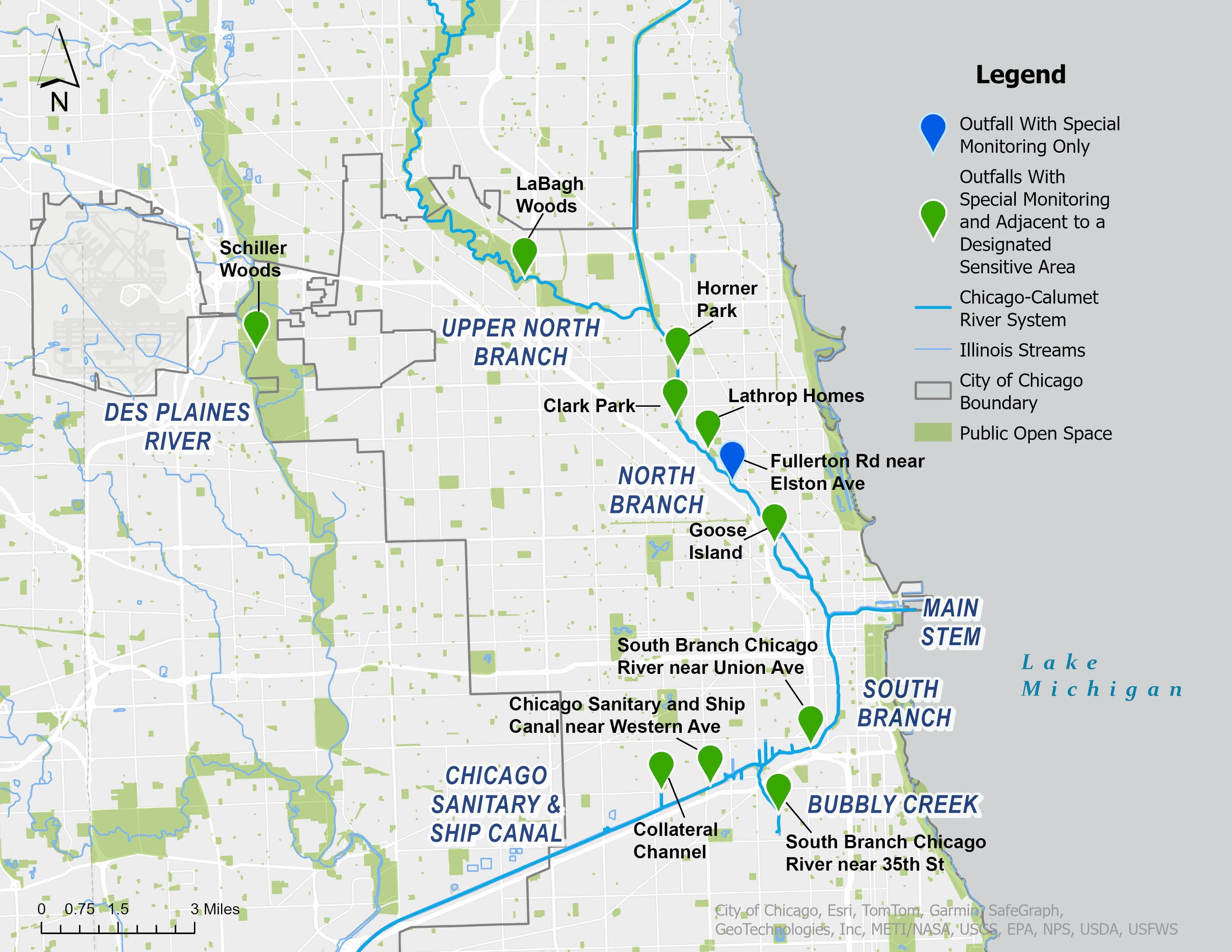

The new permit spells out advanced monitoring requirements by the Chicago Department of Water Management for 11 outfalls that have actively discharged to the river in the past few years. A new designation was created, labeling 10 of these outfalls as “Sensitive Areas” due to their locations near natural areas and facilities such as boat launches, as well as proximity to environmental justice communities.

“We’re codifying in a permit what can come out of an outfall,” said Margaret Frisbie, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River, the nonprofit that spearheaded discussions that led to the new permit language.

An outfall in LaBagh Woods, a Cook County forest preserve. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

“Chicago owns the most outfalls that discharge into the river system, and controlling what comes out of them is essential to reach our shared vision for a fishable-swimmable river that is accessible to everyone,” Frisbie said. “So that means reducing sewage, it means reducing litter pollution and monitoring what comes of an outfall when it rains so we can look back at the system and address that.”

The discharges are becoming rarer as the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District has brought more reservoir capacity online with its Deep Tunnel project. According to Nicodemus, in 2017, monitoring indicated 20 discharges from an outfall near Urban Rivers’ North Branch Wild Mile wetland, but only four discharges have been recorded since 2020.

Today, the primary concern is severe storm events, which are occurring more frequently due to climate change. That’s when the additional monitoring will be critical, Nicodemus said.

Places like Bubbly Creek are particularly vulnerable to the discharges, because of the lack of natural water flow in the channel.

“Everything that’s been dumped out is just kind of stuck, sinks to the bottom and maybe gets digested over time,” Nicodemus said. “IDNR (Illinois Department of Natural Resources) counted a massive fish kill a few years ago that saw normally robust fish species die in the hundreds, and as we went through there with our oxygen probe ... we were getting readings of literally no oxygen in the water. So it can be quite serious during the most severe storm events.”

That’s why, in a big win for river system advocates, the new permit also calls for an update of Chicago’s Green Stormwater Infrastructure Strategy. The permit calls for measurable goals to reduce stormwater runoff that results in combined sewer overflows, and a commitment to incorporating additional green stormwater infrastructure on city-owned properties.

Another requirement: the purchase and deployment of litter control technology such as skimmer boats and trash-traps to reduce floating solid waste along the river system in Chicago.

“It’s a watershed moment for the river system,” said Frisbie. “It’s coming to life, and people are treating it with the respect it deserves.”

A map of the Chicago outfalls subject to stricter monitoring. (Friends of the Chicago River)

A map of the Chicago outfalls subject to stricter monitoring. (Friends of the Chicago River)

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]