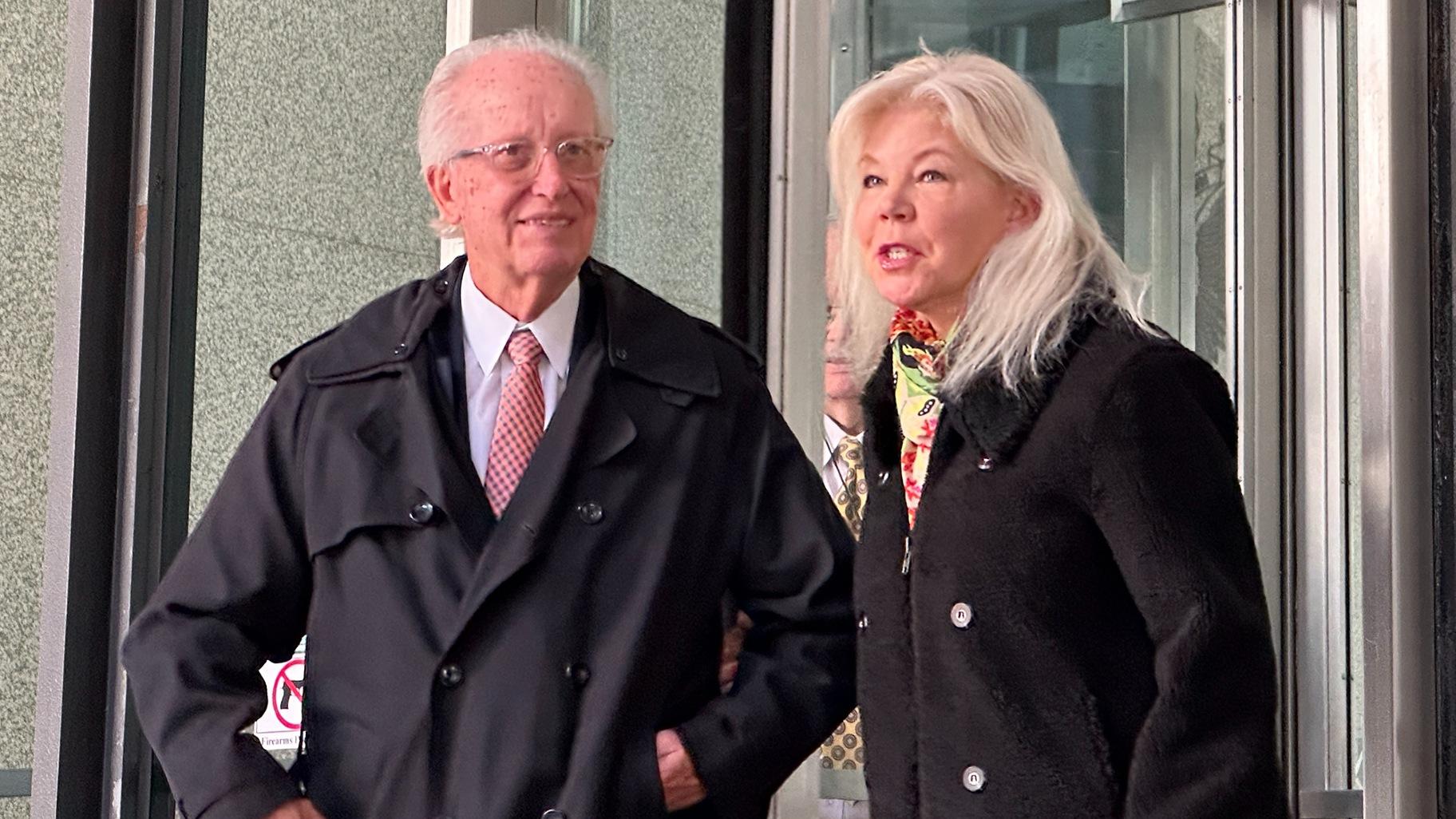

Former Democratic state Sen. Terry Link exits the Dirksen Federal Courthouse in Chicago with his attorney Catharine O'Daniel on Wednesday, March 6, 2024, after being sentenced to three years’ probation on tax evasion charges. (Dilpreet Raju / Capitol News Illinois)

Former Democratic state Sen. Terry Link exits the Dirksen Federal Courthouse in Chicago with his attorney Catharine O'Daniel on Wednesday, March 6, 2024, after being sentenced to three years’ probation on tax evasion charges. (Dilpreet Raju / Capitol News Illinois)

CHICAGO – On an August day in 2019, then-Democratic state Sen. Terry Link stood outside of a suburban Wendy’s and solicited a bribe from his colleague in the Illinois House.

“What’s in it for me, though?” Link asked then-state Rep. Luis Arroyo, who’d asked to meet up to discuss a type of video gaming machine that Arroyo had been lobbying to legalize.

But Link – the two-decade veteran of the General Assembly and former poker buddy of then-state Sen. Barack Obama – was wearing a wire. He’d been acting as a cooperating witness after the feds accused him of illegally spending campaign money on personal expenses and filing false tax returns to cover it up. He wasn’t officially charged until August 2020 and pleaded guilty to the single count the following month.

Because of that cooperation, a federal judge on Wednesday handed Link a lenient sentence of three years’ probation, matching what prosecutors recommended last week. The feds had advised probation due to Link’s “extensive cooperation,” prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memorandum, and asked that he pay nearly $83,000 in restitution, which U.S. District Judge Mary Rowland ordered.

During the brief sentencing hearing at the Dirksen Federal Courthouse, the 76-year-old Link made a public apology. Speaking slowly and with a tremor borne of a neurological condition that has worsened since he left office in 2020, Link said he’d made a mistake and “did not intend to cheat the government.”

“I accept responsibility for what happened,” Link said tearfully. “Do I feel bad about it? I feel horrible about it.”

He went on to say he’d never been “an affluent person” and never would be, casting himself as a generous person.

“If I had a dollar in my pocket, I'd give you the dollar,” Link said.

Rowland said she’d agreed to the government’s recommendation for probation and restitution, but she wondered aloud how to “send a message to the next generation” of public officials that corruption “is not how we do business.”

“While I appreciate your tax crime was not directly related to your duties, it's a terrible message to hear that someone in public service is not paying their taxes,” Rowland said.

In June, Link was the government’s star witness in the trial of Jimmy Weiss, a politically connected businessman charged with bribing both Link and Arroyo. Weiss had been pushing for the legalization of “sweepstakes machines,” a close cousin of the heavily regulated and taxed video gaming terminals found in bars, restaurants and standalone video gambling cafes across Illinois.

Arroyo is currently serving a 57-month prison sentence after eventually pleading guilty to both bribing Link and accepting bribes from Weiss, who’d been paying him to “lobby” for the machines beginning in 2018. But Weiss proceeded to trial and a jury convicted him of all seven counts of bribery and lying to the FBI. In the fall, he was sentenced to 66 months in prison.

On the stand, Link told the jury that he’d agreed to become a cooperating witness after being approached by the FBI about his taxes. He was concise when a prosecutor asked him to explain his crime.

“Underreported my income tax,” Link said, adding that he did so “I wanna say (from) 2012 or 2013 to about 2016.”

Some of the money Link had illegally used from his campaign account went to help a longtime friend who had been in the throes of family and business problems, he said in June. But not all of it.

“I used some of it for gambling,” Link admitted at the time, although it was not mentioned Wednesday.

Link’s attorney did note Wednesday that the friend to whom Link loaned money has since died, never having repaid the money.

After Arroyo’s arrest in late October 2019, Link falsely denied reports that he was the unnamed cooperating witness described in his colleague’s charging documents.

Earlier that year, Link had finally achieved his decadeslong ambition to bring a casino to his native Waukegan as part of a long-fought expansion of Illinois’ gambling industry. Link got emotional on the Senate floor before his colleagues’ final vote to approve the massive piece of legislation.

The gambling expansion law, however, did not include any language about the sweepstakes machines, which operate in a legal gray area and have been neither outlawed nor regulated in Illinois.

Arroyo made a last-minute play to include the sweepstakes machines in the larger bill. But Link rebuffed him, testifying during trial last year that he’d told Arroyo to “get the f--- out of here” after his colleague approached him on the Senate floor.

A few months later, at the FBI’s behest, Link called Arroyo and apologized for blowing up at him in the waning days of legislative session. With the FBI listening in, Link suggested the two meet to talk about the sweepstakes machines.

When Link met with Arroyo at a Highland Park Wendy’s a couple weeks later, Weiss was in tow to explain his sweepstakes machine business and make the case for legalizing the devices. Link then asked Arroyo to step outside the restaurant to talk. Despite assuring him that it was “you and I talking,” Link was secretly wearing an FBI recording device, with agents sitting in vehicles nearby taking photos of the interaction.

FBI surveillance footage shows then-state Sen. Terry Link, D-Vernon Hills, speaking with then-state Rep. Luis Arroyo, D-Chicago, outside a Wendy's in Highland Park in August 2019. Link had been wearing a wire when Arroyo offered him a bribe. (Photo submitted as evidence in federal trial of James Weiss)

FBI surveillance footage shows then-state Sen. Terry Link, D-Vernon Hills, speaking with then-state Rep. Luis Arroyo, D-Chicago, outside a Wendy's in Highland Park in August 2019. Link had been wearing a wire when Arroyo offered him a bribe. (Photo submitted as evidence in federal trial of James Weiss)

When Link asked what was in it for him, Arroyo responded that Weiss had been paying him as a consultant and implied Link could receive a similar payout. At a subsequent meeting, Arroyo gave Link a $2,500 check, which was to be the first in a series of monthly installments, saying “this is the jackpot.”

Arroyo was arrested two months later.

In sentencing Link on Wednesday, Judge Rowland noted the bevy of corruption trials the federal courthouse has seen in recent years, which will continue this year with the trial of former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan.

She said Link’s case painted a picture of Springfield as a place where someone can walk up to an elected official and ask for a bill to be passed “and on a dime you could say, ‘What’s in it for me?’ and we’d be off to the races with a federal case?”

“That’s despicable,” Rowland said.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of print and broadcast outlets statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.