(MD Duran / Unsplash)

(MD Duran / Unsplash)

SPRINGFIELD – As the cost of higher education continues to rise in Illinois and elsewhere, a growing number of students are working to earn as many college credits as possible while they are still in high school.

But even as the popularity continues to grow for “dual credit” offerings – courses in which a student earns credit toward both a high school diploma and a college degree – a new study shows disparities between racial, economic and geographic groups are also widening.

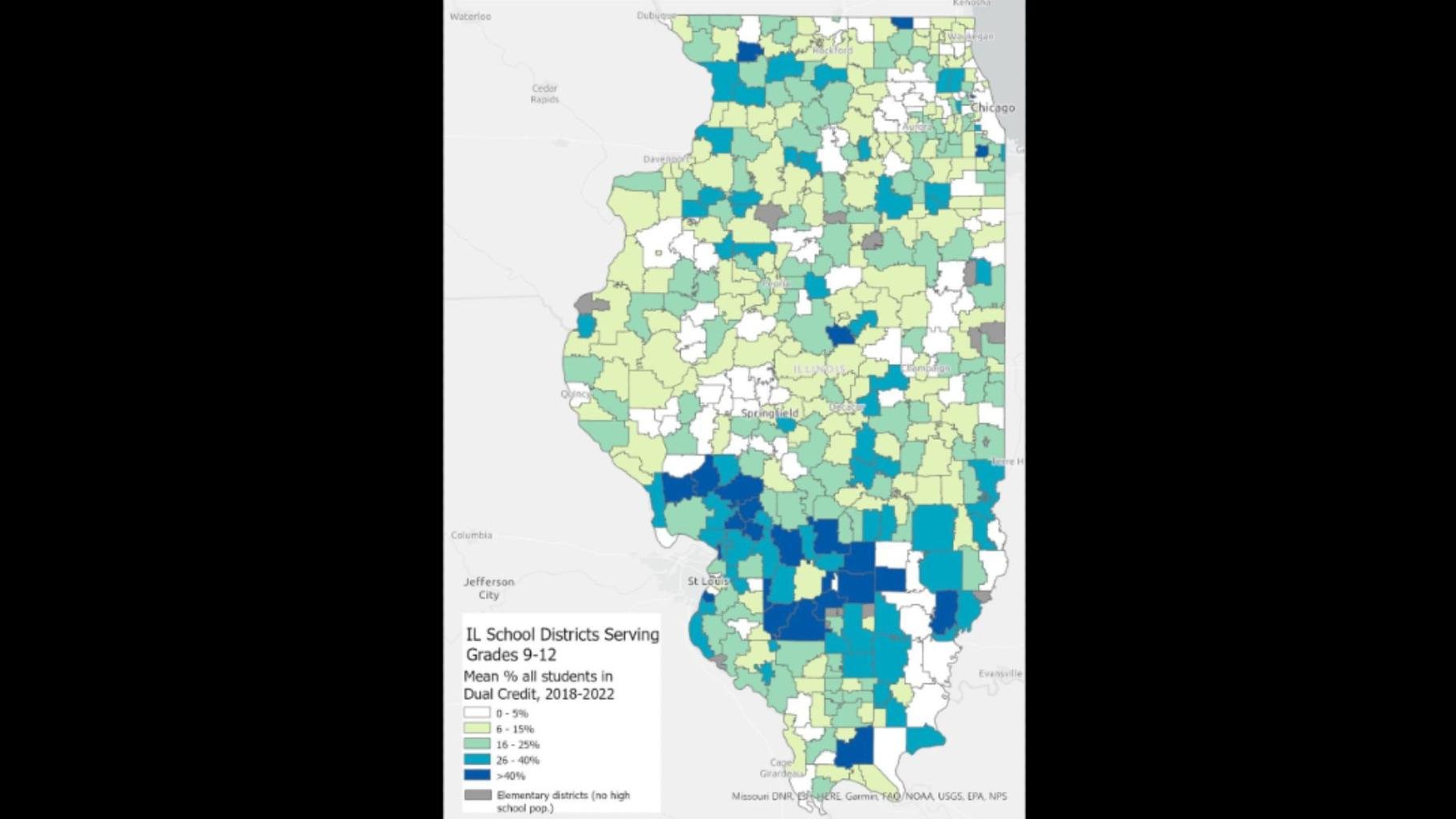

According to the study, dual credit programs are more prevalent in districts that serve rural communities and small towns in downstate Illinois than in suburban and urban districts. They are less prevalent in districts that serve minority and lower-income students.

And even within individual districts, the study found that white students and those from more affluent backgrounds were more likely to enroll in and complete dual credit courses than minority students or students from lower-income households.

The study was conducted by the Illinois Workforce & Education Research Collaborative, or IWERC, a research arm of the University of Illinois System’s Discovery Partners Institute, which works to develop the state’s high-tech workforce and economy.

Dual credit courses are offered through partnerships between high schools and postsecondary institutions.

According to the study, a small number of dual credit courses are offered through public four-year universities, but the overwhelming majority – about 97 percent – are offered through local community colleges. As a result, the courses offered in any given high school are strongly influenced by the policies and programs of the community college district that overlaps with the high school district.

Sarah Cashdollar, an IWERC researcher and author of the report, said in an interview that details of those partnership agreements may help explain some of the disparities between school districts and between different geographic areas.

“It is costly to provide dual credit, especially for community colleges,” she said. “Depending on the partnership, it can also be costly for the school district. And so there might be variation in terms of how community college districts have managed those costs.”

Although students typically pay some tuition to enroll in a dual credit course, Cashdollar said the cost is typically only a fraction of what students would pay otherwise, which is one of the reasons why dual credit programs help lower the overall cost of higher education.

In recent years, Illinois lawmakers have taken several steps to make dual credit programs more accessible and affordable.

Among those actions is the Dual Credit Quality Act, first passed in 2010 and amended several times since then, which requires public colleges and universities to accept credit from those courses if a standard agreement is in place. It also requires community colleges to enter into dual credit agreements with any high school in their district that requests one.

The Education Workforce Equity Act, passed in 2021, provides that starting this year, high school students who meet or exceed state standards on their annual assessments in English language arts, math, or science may automatically be enrolled the following year in the next most rigorous level of advanced coursework offered by the school. For seniors, that must include a dual credit, Advanced Placement, or International Baccalaureate course.

And this year’s state budget includes just over $3 million for community colleges to help them lower the cost of dual credit programs.

Despite those efforts, however, the study found that while overall participation in dual credit programs has grown – from 10.2 percent of high school students in the 2018 school year to 14 percent in 2022 – the racial and economic disparities in participation rates and completion rates has widened.

That was due mainly to the fact that participation rates grew more slowly among students of color and students from lower-income backgrounds than they did among white and Asian students and students from more affluent backgrounds.

Cashdollar noted those kinds of achievement gaps are similar to the gaps that researchers find in other aspects of education, including college enrollment rates and college completion rates. And because dual credit programs are, by definition, intended for students who aspire to continue their education beyond high school, she said the gaps point to differences in the types of students who are seen as being college-bound.

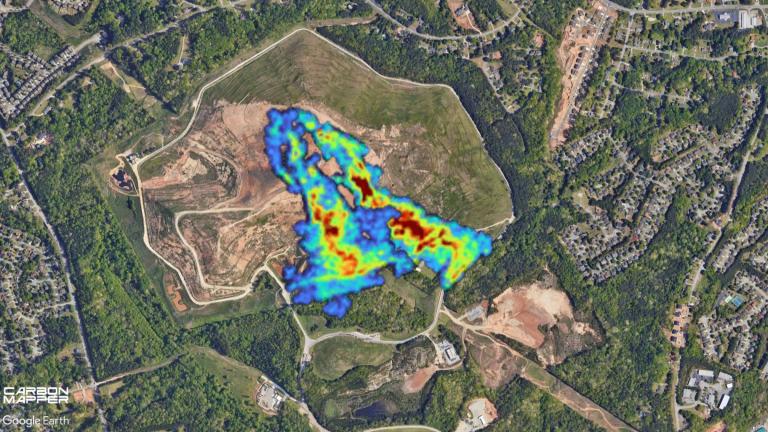

Dual credit programs that allow students to earn both high school and college credit simultaneously are more available in southern Illinois districts than in other parts of the state. (Credit: Illinois Workforce & Education Research Collaborative)

Dual credit programs that allow students to earn both high school and college credit simultaneously are more available in southern Illinois districts than in other parts of the state. (Credit: Illinois Workforce & Education Research Collaborative)

She said prior research on the topic has found the biggest predictor for racial gaps in students enrolled in dual credit was enrollment in accelerated coursework taken prior to high school.

“So who are those kids who are in the gifted classes? Who are taking algebra in eighth grade? Who are the kids in the honors program, maybe at the middle school?” she said. “And it's kind of like, that sets the wheel in motion in terms of who is then either tracked into these higher-level courses, who is thinking about themselves as the type of kid who takes these courses.”

The report recommends the state continue investing in efforts to make dual credit programs more accessible and affordable but that it focus on increasing dual credit offerings in districts that currently have the lowest participation rates, especially urban and suburban districts.

“Only by attending to these issues of representation can the potential for (dual credit) coursework to reduce inequities in postsecondary educational attainment be fulfilled,” the report concludes.

Editor’s note: The IWERC study was funded by a grant from The Joyce Foundation, a private, nonpartisan philanthropy organization whose mission is to invest in public policies and strategies to advance racial equity and economic mobility. The Joyce Foundation provides matching funds for donations received by Capitol News Illinois during our end-of-year fundraising campaigns. Capitol News Illinois donors, including the Joyce Foundation, have no influence over our news coverage or story selection.

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of newspapers, radio and TV stations statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.