Trashion Revolution will feature designs made from plastic pollution, like the two pictured above. "I am just blown away by the designs," said Jordan Parker. Photos provided by the designers. (Alan Emerson Hicks, left / Jess Crane, right)

Trashion Revolution will feature designs made from plastic pollution, like the two pictured above. "I am just blown away by the designs," said Jordan Parker. Photos provided by the designers. (Alan Emerson Hicks, left / Jess Crane, right)

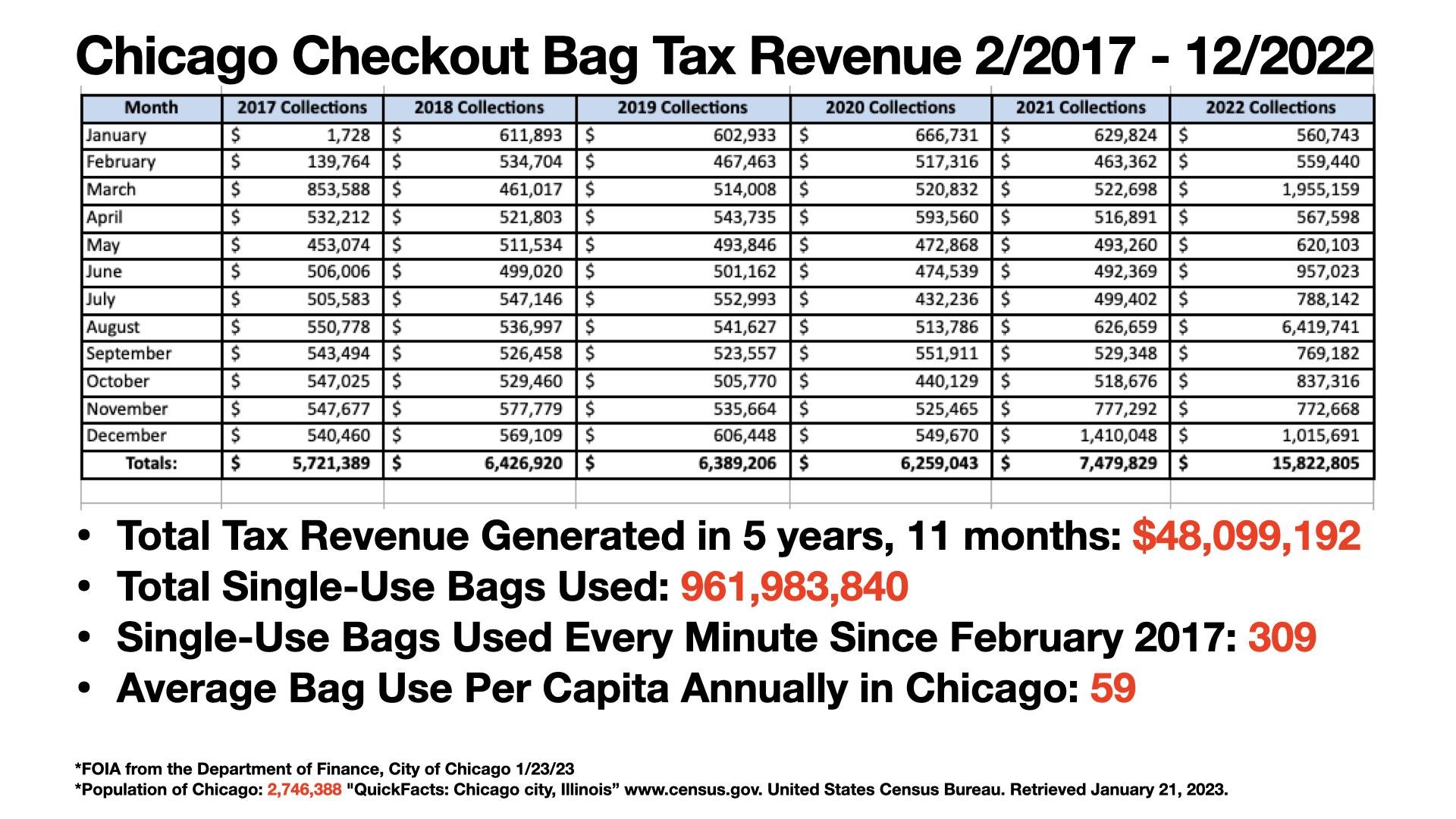

Every minute, 309 single-use bags are dispensed from checkouts in Chicago.

At that volume, a 7-cent bag tax that’s been in place since 2017 adds up quickly, to the tune of $6 million per year.

“In terms of padding city coffers, it’s been a huge success,” Jordan Parker said of the tax. In terms of reducing plastic consumption, not so much.

The roughly $50 million the city collected from the tax between 2017 and 2022 translates to nearly 1 billion bags, she said.

Parker, as founder of the grassroots environmental movement Bring Your Bag Chicago, was one of the driving forces behind the tax. The fee, she said, was never meant to be a revenue generator. It was supposed to be a deterrent and a way of encouraging the adoption of reusable bags.

“Anecdotally, I saw a lot more reusable bags, initially,” said Parker. “But over time, people have adapted. People are just absorbing it (the tax).”

(Courtesy of Triveni Institute)

(Courtesy of Triveni Institute)

There are myriad reasons behind what she would term a failed policy, from the tax being too low to a lack of emphasis on the fee at the point of checkout — the difference between being asked, “Do you need a bag?” and “Do you want to pay 7 cents for a bag?”

“For the bag tax to trigger loss aversion, the customer has to know they’re paying it,” Parker said.

The COVID-19 pandemic also set back momentum, she said, not just on reusable bags but practices like people bringing their own mugs to coffee shops. Starbucks pulled the plug on reusable cups in early March 2020, before stay-at-home orders were even issued.

It’s time for a reset, Parker said, not just when it comes to policy but the approach toward tackling the problem.

The sheer scope of plastics pollution — from microplastics in clothing to “forever” chemicals in our water — can be overwhelming, stressful and scary, leading to what could best be called “plastics fatigue.”

“It’s a monumental undertaking to try to reduce the plastic in our world. We’re just drowning in it,” Parker said. “It gets really big, really fast, and it’s easy to disengage and say, ‘We’re screwed. So why even bother?’”

Which is why she’s introducing a little levity to the situation.

The upcoming Trashion Revolution event will highlight the problem of single-use plastic bags. (David Smith / Triveni Institute)

The upcoming Trashion Revolution event will highlight the problem of single-use plastic bags. (David Smith / Triveni Institute)

On Saturday, Parker’s Triveni Institute Foundation is hosting Trashion Revolution at the State Street Macy’s, an event using fashion to raise awareness of plastic pollution and climate change.

In what sounds like a classic “Project Runway” challenge, designers are taking plastic pollution and turning it into “clothing,” like a ballgown made out of red Solo cups or a kimono stitched together from coffee filters and dog food bags.

“The magic is that it’s so fun. Looking at these designs makes people laugh,” Parker said. “It makes people smile, it makes people laugh, and then they lean in.”

The Trashion event will be the launch for Bring Your Bag 2.0, Parker’s renewed push to reenergize the movement to cut the consumption of single-use bags, which she considers low-hanging plastics fruit, along with bottled water.

“We need to start normalizing reusables,” she said.

With a new mayor in office, the most progressive City Council in history just sworn in, and a new chairperson — Ald. Maria Hadden (49th Ward) — leading the council’s environment committee, Parker said she plans to pound the pavement in the coming months to marshal support for a new policy. That could take the form of a higher tax or a ban.

But she also acknowledged that it’s important to connect work on plastics reduction to other environmental battles across Chicago.

“If my child goes to day care six blocks from MAT Asphalt and some White lady gets on TV and says I have to pay for bags, I’m going to roll my eyes,” Parker said.

Yet while there may not be a plastics industry in Chicago, there is “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana and a growing plastics hub in the Ohio River Valley, she said.

“This is an environmental justice issue; these issues are all interconnected,” Parker said. “It’s about the habitability of our planet.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]