For the most part, free public education in the U.S. starts at the kindergarten level, when children are around age 5. But research continues to reveal just how critical the first few years after birth are to long-term outcomes. Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s proposed Smart Start program would allow an additional 5,000 kids to go to preschool next year, eventually adding a total of 20,000 slots. The plan would also add money to increase wages for early education providers.

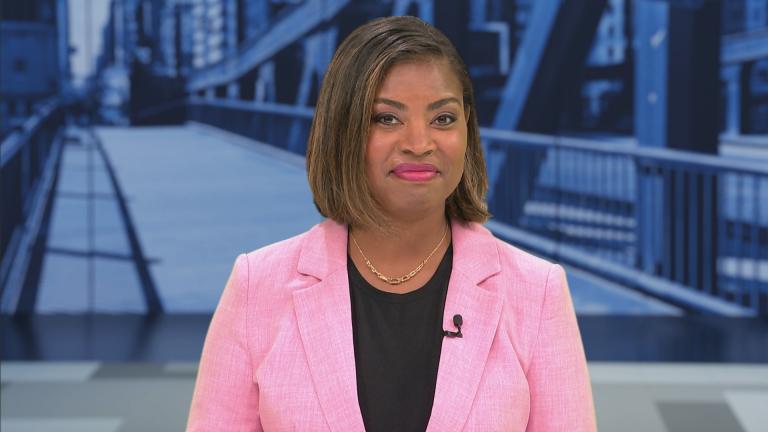

Illinois Action for Children CEO April Janney said she thinks Pritzker’s proposal is the next iteration of making Illinois a leader in early childhood education.

“I think Illinois overall has been out there in front,” Janney said. “We’ve been focused on the littlest learners for a long time and investing in that area, and I think we have started out investing more over these years.”

Providing resources to pay early education teachers more is an approach Meghan Gowin of the Erikson Institute said she would expect to have a strong positive impact. Erikson Institute recently launched a teacher education program that provides three key endorsements — special education, bilingual/ESL and early childhood — in an effort to speed certification to fill teacher shortages and diversify the teaching workforce.

“I actually started my career as a pre-K teacher assistant,” Gowin said, “and so making the transition later on to get that early childhood teacher credential, it was to support my young children. They were 4 months and 2 years old at the time. I think this investment in our workforce to really make sure that they are well compensated is going to only increase that push towards quality.”

Janney said that although early education teachers have seen certification requirements for their positions increase, their salaries have remained low.

“The majority of them are women, the majority of those women are Black women,” Janney said. “And so having them to push their training and get better education is the cost to them, but then we’re not paying them as professionals.”

Part of that mindset has historically been rooted in a custodial model of care for very young children versus education, said Sonja Crum Knight, chief programs and impact officer at the Carole Robertson Center for Learning.

“It’s really turning those old notions of child minding on its head, right?” Crum Knight said. “This is work that is historically not valued because it’s done by women of color. If we think about what it takes for high quality early care and education, that teacher training and the relationship with the child is central. So when you increase the wages, and you build that workforce through higher educational attainment, you are ensuring high quality outcomes for children. That is the sauce that’s not so secret, but it’s there.”

Gowin said the prospect of seeing more financial resources flow into a system long pressed for resources is a step toward delivering early childhood education more equitably.

“I think the investment in quality programs and the money that is earmarked for providers to really build up their own infrastructure, the money that we know is built into supporting the workforce … we’re now seeing where this investment is putting that financial push into the system, right?” Gowin said. “We’ve heard it. Everyone cares about young children and families, but now we see it in dollars.”

Note: This story was updated on March 20 to correct the spelling of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning.