A Cicero woman is calling on Chicago officials to release the full probe completed by the city’s inspector general into how the Chicago Police Department investigated the 2016 murder of her 22-year-old son.

Courtney Copeland died while handcuffed after asking police officers for help after being shot. More than seven years after Copeland’s death, no one has been charged with his murder, and his mother, Shapearl Wells, is left with few answers.

“It’s very painful,” Wells said. “Seven years, and we still don’t have the answers. We still don’t know what happened to my son. Seven years, I’m still fighting, trying to find the truth.”

Wells said she remains determined to solve her son’s murder and will not stop demanding answers from the Chicago Police Department, which she said botched not only its response to Copeland’s plea for medical assistance but also the investigation into his murder.

“It is important to find out what happened to Courtney on that night,” Wells told WTTW News, just steps from where her son collapsed. “We know something tragic occurred to him, because we see him on tape begging for his life.”

Wells partnered with journalist Jamie Kalven and the Invisible Institute to create the podcast “Somebody,” a 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist, that sought answers about both her son’s murder and the Police Department’s search for his killer.

Kalven was the first journalist to report that the police video of the death of Laquan McDonald in 2014 contradicted the department’s report that McDonald was shot after he threatened officers with a knife. In fact, the video showed the teen walking away from officers before being shot 16 times, even after he collapsed.

On the podcast, Wells remembered her son as energetic and outgoing. He was shot and killed shortly after leasing a new BMW — a tangible sign of the success he was experiencing while working for a firm that offered discounted vacations.

“He had this bubbly personality, he was full of life,” Wells said. “He made everyone feel special as if they were his best friend. That’s how I want him to be remembered.”

Copeland was driving that BMW on March 4, 2016, when he was shot in the back on Chicago’s Far Northwest Side. Copeland made it to the police station at Grand and Central avenues, the headquarters of the 25th Police District, and pleaded for help before collapsing.

Approximately 13 minutes passed before an ambulance carrying Copeland departed for a trauma center. In the ambulance, Copeland’s heart stopped, according to documents obtained by the Invisible Institute.

“That cost my son his life,” Wells said. “I am certain that if my son had immediately gotten the help that he needed, my son would be alive to tell his story today.”

When the ambulance arrived at the hospital, Copeland was in handcuffs, according to reporting by the Invisible Institute.

That reporting prompted former Inspector General Joseph Ferguson to launch a probe into the investigation of Copeland’s death — and the treatment of Wells.

A summary of the results of that probe was released in January, as required by city law. But Wells wants the full report to be public as part of her effort to prevent another mother from suffering the same pain.

“If we can save other Courtneys from happening,” that makes the fight worthwhile, Wells said.

The full report needs to be released to pressure city officials to make changes to protect Chicagoans, Wells said.

City officials rejected a Freedom of Information Act request filed by the Invisible Institute and Wells for the inspector general’s report. A spokesperson for the city’s Law Department said that request was denied because the report remains with the Office of the Inspector General, now led by Deborah Witzburg.

The Chicago City Council approved an ordinance in July 2019, backed by Mayor Lori Lightfoot, that gave the city’s top lawyer the power to release investigations from the inspector general about cases involving deaths or felonies. The decision whether to release the report rests with Corporation Counsel Celia Meza, who reports to Lightfoot, who lost her bid for reelection last month.

The mayor’s office did not respond to a request for comment from WTTW News. Meza told Wells she would respond to her request for the full inspector general's report by March 28, according to a copy of an email obtained by WTTW News.

Once Wells makes a formal request for the full report, it should be released immediately, Kalven said.

“As a society, as a city, we have a moral obligation that is really imperative when tragedies like this occur to learn everything we can possibly learn toward the future, toward reducing similar harms in the future,” Kalven said.

The fact that the city’s top lawyer has the sole power to keep this report hidden from the public creates a “black hole” in efforts to reform the Chicago Police Department, Kalven said.

The probe recommended two members of the Chicago Police Department face discipline for the way they responded to Copeland’s death, but neither officer faced serious punishment for their role in Copeland’s death. Neither was named in the summary of the inspector general’s report, in keeping with city rules.

Wells called that an “insult.”

No member of the Chicago Police Department documented when and why Copeland was handcuffed. In addition, a sergeant violated department policy by failing to require the police officer “who placed the victim in handcuffs at some point prior to transport accompanied them in the ambulance to the hospital,” according to the summary of the inspector general’s report.

Wells said the fact that it took so long for Copeland to get to the hospital and then doctors and nurses had to wait to treat her son until after the handcuffs were removed contributed to his death.

The sergeant was reprimanded by police officials, but the department declined to impose harsher penalties on him because the inspector general failed to find “by a preponderance of the evidence that the victim was, in fact, handcuffed prior to being transported to the hospital,” according to the summary of the inspector general’s report.

There is no evidence paramedics handcuffed Copeland while he was in the ambulance, dying.

“As if this was a figment of my imagination, that’s what the anger comes because it basically tells me that my son’s life didn’t mean anything,” Wells said. “That’s tragic for me.”

The city’s watchdog urged the Police Department to “review its policy regarding the provision of first aid to injured persons to ensure that it complies with a recent change in state law, and also review its policy and training on the transportation of injured persons to hospitals by CPD members.”

In March 2016, Chicago Police Department policy required officers to provide first aid to those they had shot or otherwise injured but not to those who sought their aid.

That policy remains unchanged, according to the department’s website.

However, a revised state law that took full effect Jan. 1 requires officers to render medical aid to anyone who needs help, if it is possible. State law trumps the police department’s policy.

The inspector’s general’s probe also found that a “detective who conducted the investigation into the victim’s homicide was disrespectful to or mistreated a member of the victim’s family during a meeting,” according to the summary of the report.

Wells recorded her conversations about her son’s murder with detectives, pressing them for information about why her son was handcuffed after he was shot and asked for help. Wells was also highly critical of the investigation into her son’s murder, telling police they had not done everything possible to find his killer because he was a Black man.

The detective resigned from the Chicago Police Department before the probe’s conclusion, and the inspector general recommended that he be ineligible to be rehired by the city. Chicago police officials declined to do so, although they placed a copy of the inspector general’s report in his employment file.

The inspector general urged the Police Department to review its policy “regarding communications, interactions with, and services to victims of violent crimes and their family members,” according to the report’s summary.

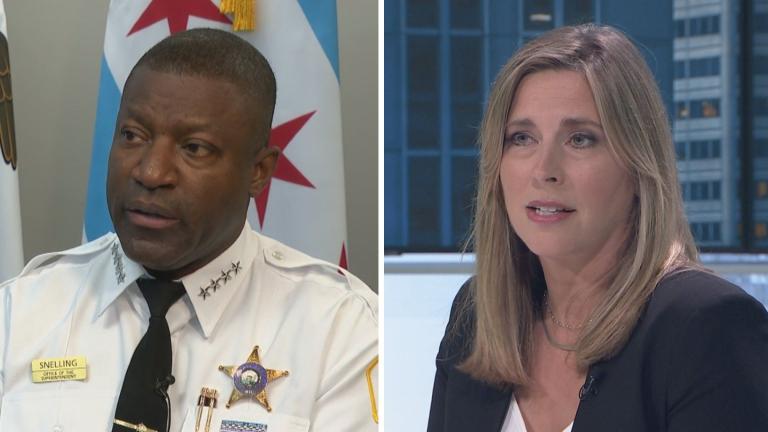

Since the probe into the investigation of Copeland’s murder involves a death and includes findings of misconduct, it meets the criteria to be released under the city’s law, but Meza is under no obligation to do so, Witzburg told WTTW News.

The way police officers treat victims has a “clear impact” on efforts to rebuild Chicagoans’ trust in the Police Department, Witzburg said.

“Inaction and mistreatment are the building block of illegitimacy for any police department,” Witzburg said.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]