Mayor Lori Lightfoot fields questions from the news media on Feb. 7, 2023, after the WTTW News mayoral forum. (Michael Izquierdo / WTTW News)

Mayor Lori Lightfoot fields questions from the news media on Feb. 7, 2023, after the WTTW News mayoral forum. (Michael Izquierdo / WTTW News)

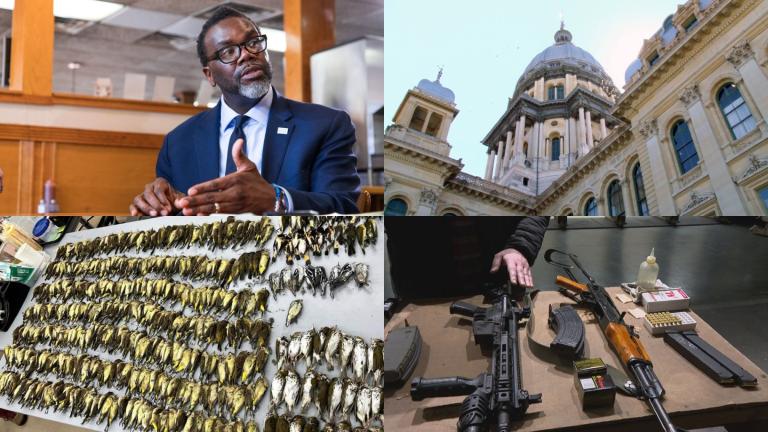

A political action committee created by close allies of Mayor Lori Lightfoot to boost her bid for reelection — fueled with cash from firms doing business with the city of Chicago — entered the political fray on Tuesday with an advertisement attacking Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson.

The 15-second ad and the committee’s operations have been funded by $155,000 in contributions from four firms doing business with the city, records show, including a $50,000 check from a firm owned by a prominent political donor that won a $23.5 million contract in December to help extend the CTA Red Line south to 130th Street.

Those contributions exploit what campaign finance experts told WTTW News is a loophole in laws governing the role of money in Chicago’s elections opened up by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to lift most limits on campaign spending.

Former Inspector General Joseph Ferguson, a harsh critic of Lightfoot, said that while the political activity by The 77 Committee is legal, it is “unethical.”

“Any Chicagoan will tell you: ‘Well, jeez, that’s a quid pro quo,’” Ferguson said. “It doesn’t pass the smell test.”

The 77 Committee is run by Dave Mellet, a longtime top political adviser to Lightfoot, who said the committee operates independently of any campaign for mayor, as required by law.

“We do not communicate or coordinate with any of the campaigns for mayor and all decisions on strategy, fundraising and expenditures are made solely by the committee,” Mellet said in a statement to WTTW News.

Lightfoot’s campaign told WTTW News in a statement that the mayor is focused on her own campaign and “has no control over any outside groups or organizations” and is prohibited by law “from communicating directly with the entity in question on any strategic issue.”

However, the Lightfoot campaign welcomed “efforts to support her agenda of making Chicago safer, fairer and more equitable for all.”

Companies doing business with the city, as well as the city’s sister agencies, including the Chicago Transit Authority, can only give $1,500 per calendar year to any city official or candidate or to their political committees, under the city’s Governmental Ethics Ordinance.

Those limits are designed to prevent city contractors and officials from engaging in pay-to-play politics, a significant source of corruption that has dogged Chicago politics for decades, according to Alisa Kaplan, executive director of Reform for Illinois, a group that tracks campaign contributions and lobbies for increased transparency in government.

“Of course, it looks bad because a candidate or elected official knows who's donating to those committees and can grant favors in return for a big donation,” Kaplan said. “The public could reasonably believe there's a quid pro quo, even if there isn't one.”

There are no limits on what city contractors can give to campaign funds like The 77 Committee that are not directly controlled by a candidate, giving wealthy supporters a way to get around city limits on campaign contributions and help their chosen candidate.

Lightfoot is neither the first Chicago mayor nor the only candidate in this year’s race to benefit from such a committee. In 2015, allies for former Mayor Rahm Emanuel formed a similar political fund. In this year’s race, the Chicago Leadership Committee is boosting the campaign of former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas. That group appears to be funded by a group registered in Philadelphia, not city contractors, according to Crain’s Chicago Business.

Four firms listed by the city as contractors — ELH Partners, Killerspin, Christy Webber Landscapes and Ujaama Construction — have given a combined $155,000 to The 77 Committee, which was “established to support continued strong, equitable and thoughtful leadership for Chicago in the municipal elections,” according to records filed with the Illinois State Board of Elections.

That represents 94% of the funds collected by The 77 Committee, whose name is a reference to Chicago’s 77 community areas. On the campaign trail, Lightfoot frequently talks about the need for all parts of Chicago to receive attention and resources from the city’s government.

Had those firms chosen to contribute directly to Lightfoot’s campaign, they would have only been able to contribute a combined $6,000 under the city-imposed limits on campaign contributions.

ELH Partners is a property management firm owned by prominent businessman Elzie Higginbottom, who sold the Chicago Reader last year and was an investor in the Chicago Sun-Times. Higginbottom, a frequent political donor, also served as fundraiser for former Mayor Richard M. Daley and other prominent Democrats.

Higginbottom, who also owns East Lake Management Group, manages apartments subsidized by the Chicago Housing Authority and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The CTA Board of Directors in December selected Higginbottom’s East Lake Management Group for a four-year $23.5 million property management contract that is part of the extension of the CTA Red Line south to 130th Street after “a competitive bid process that was open to the public and conducted in accordance with CTA’s Procurement Policy and Procedures,” according to a statement from a CTA spokesperson.

Higginbottom did not respond to a request for comment from WTTW News.

The 77 Committee deposited the $50,000 check from ELH Partners on Jan. 31, records show.

Ujamaa is building an affordable housing development on city-owned vacant land in Woodlawn and is helping to build the Obama Presidential Center. Firm President Jimmy Akintonde did not respond to a request for comment from WTTW News.

Killerspin owner Robert Blackwell Jr., did not respond to a request for comment. Blackwell also owns Electronic Knowledge Interchange, an IT company that has been paid approximately $50 million by the city since 2002, according to city records.

The 77 Committee reported contributions of $80,000 from Killerspin and $20,000 on Oct. 27, records show.

The ad from The 77 Committee, which attempts to paint Johnson as “too extreme” for Chicago, cost The 77 committee more than $71,000, about half of the funds it has on hand entering the final weeks of the campaign, according to records filed with the Illinois State Board of Elections.

Until this week, Lightfoot had been publicly dismissive of Johnson’s chances in the race for mayor, even as he campaigns with the backing of the Chicago Teachers Union and a coalition of progressive political groups. Lightfoot’s campaign spent much of its time and money focused on two other candidates in the race, U.S. Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García and Vallas, but attacked Johnson at a Thursday night debate for wanting to reduce the Chicago Police Department’s budget.

Representatives of Johnson’s campaign referred questions to Emma Tai, the executive director of United Working Families, a political organization closely aligned with the Chicago Teachers Union, that backed Johnson’s candidacy.

The decision by allies of the mayor to attack Johnson using funds from big city contractors is a sign Lightfoot is losing ground as Johnson’s campaign gains momentum, Tai said.

“It is unfortunate that a candidate who campaigned on ‘bringing in the light’ would engage in these kind of tactics,” Tai said, referring to Lightfoot’s 2019 campaign slogan. “It is a tale as old as time.”

Lightfoot’s campaign for a second term has been weighed down by a growing amount of evidence that not only has she failed to fulfill campaign promises to root out corruption but also that she has at times governed more like an old-school machine politician than a reformer. For her part, Lightfoot has said that her administration has made strides in pushing back against corruption.

Corporations are worried that in a Johnson administration they would have to pay higher taxes and endure a less cozy relationship with City Hall, Tai said.

“They are scared they will be forced to pay something back to the community,” Tai said.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]