For the first time, the James Webb Space Telescope has been used to directly image an exoplanet — that’s a planet outside of our solar system.

Although it’s not the first time an exoplanet has been directly imaged, it is the first time the Webb Telescope’s powerful gaze has been turned to the task.

And these, along with future observations could tell us more about alien worlds beyond our solar system than ever before — and just maybe, even detect life.

Jason Wang, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA), spoke with WTTW News.

Wang was part of the Webb team that produced the exoplanet images. (The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

WTTW News: This is the first time the Webb Telescope has been used to directly image a planet outside our Solar System, but it’s not the first time an exoplanet has been imaged, how does the Webb image compare to previous images that have been captured?

Wang: I think the main thing is it’s taken at different wavelengths. We’re looking at a wavelength that we’ve never seen exoplanets before directly. So that’s really exciting for us because it allows us to see different parts of the planet’s atmosphere. Look at different molecular absorption features … look at different molecular species in the atmosphere to understand composition. It also allows us to measure the total energy budget of the planet. So, being able to look at these other wavelengths that are in particular inaccessible from ground-based telescopes is really exciting.

Why was this particular planet selected? We’re aware of many exoplanets at this point. Why was this one selected as a target for Webb?

That’s a great question. So it comes down to kind of to two things. One is we have detected thousands of exoplanets, but only a handful of them can be directly imaged because we can only see and take pictures of the youngest exoplanets. So this planet is only a few million years old, whereas the Earth is 4.5 billion years old. So it’s a 1,000 times younger. It’s so young that it formed after the dinosaurs went extinct. And because it’s so young, it’s actually glowing hot from its formation. It still retains that heat. And because of that, it’s very bright and that’s how we’re able to actually take an image of it.

I had read that the planet was a gas giant many times the size of Jupiter and I assumed it was the size that made it a good target.

You know, the size also helps, but really it’s the age that is the key.

And so in terms of the light that you’re detecting, you’re not simply detecting the planet reflecting the light from its sun, but you’re seeing the light that’s reflected in terms of heat from the creation of the planet.

Yeah, we’re seeing the thermal glow of the planet basically.

The Webb telescope has astronomers all over the world excited. I would think there must be a very long line of astronomers that wants to work on Webb. How did you get to be one of the fortunate ones?

So this one, it ends up being a lot of us are the fortunate ones. This particular target and these particular images that were taken, which are among the first images taken with Webb, is part of this program that NASA came up with called the early release science program. Basically, the goal is to use Webb to do a bunch of science (experiments) that are designed to showcase the instrument’s performance for the scientific community. So basically the entire community of exoplanet imagers — those of us that like to take images of exoplanets — got together and basically submitted this program to basically test out Webb.

In terms of the challenges of imaging an exoplanet, I’m sure there must be many, but what are some of the chief challenges?

To kind of give you a sense for the challenge, it’s like trying to see a firefly orbit a streetlight, but you’re standing a few miles away. So it’s really like if you’re trying to see this firefly from several miles away with some binoculars … you have to remove all this glare, suppress the glare of the star to be able to see the planet that’s orbiting around it.

So how is that done? Is it just because Webb is so sensitive and it’s capturing so much light that you can do this or do you have to do a lot of image processing? How does that work?

So we do have to use a little bit image processing but we also take advantage of the Webb. The optics of the Webb were designed specifically to image exoplanets. It has a series of optics built in it called coronagraphs. And these are designed to kind of block out the light of the star as much as possible so that we could see the faint light of the planet. But usually that’s not enough. What we have to do is then also do image processing after the fact to discern these faint planets.

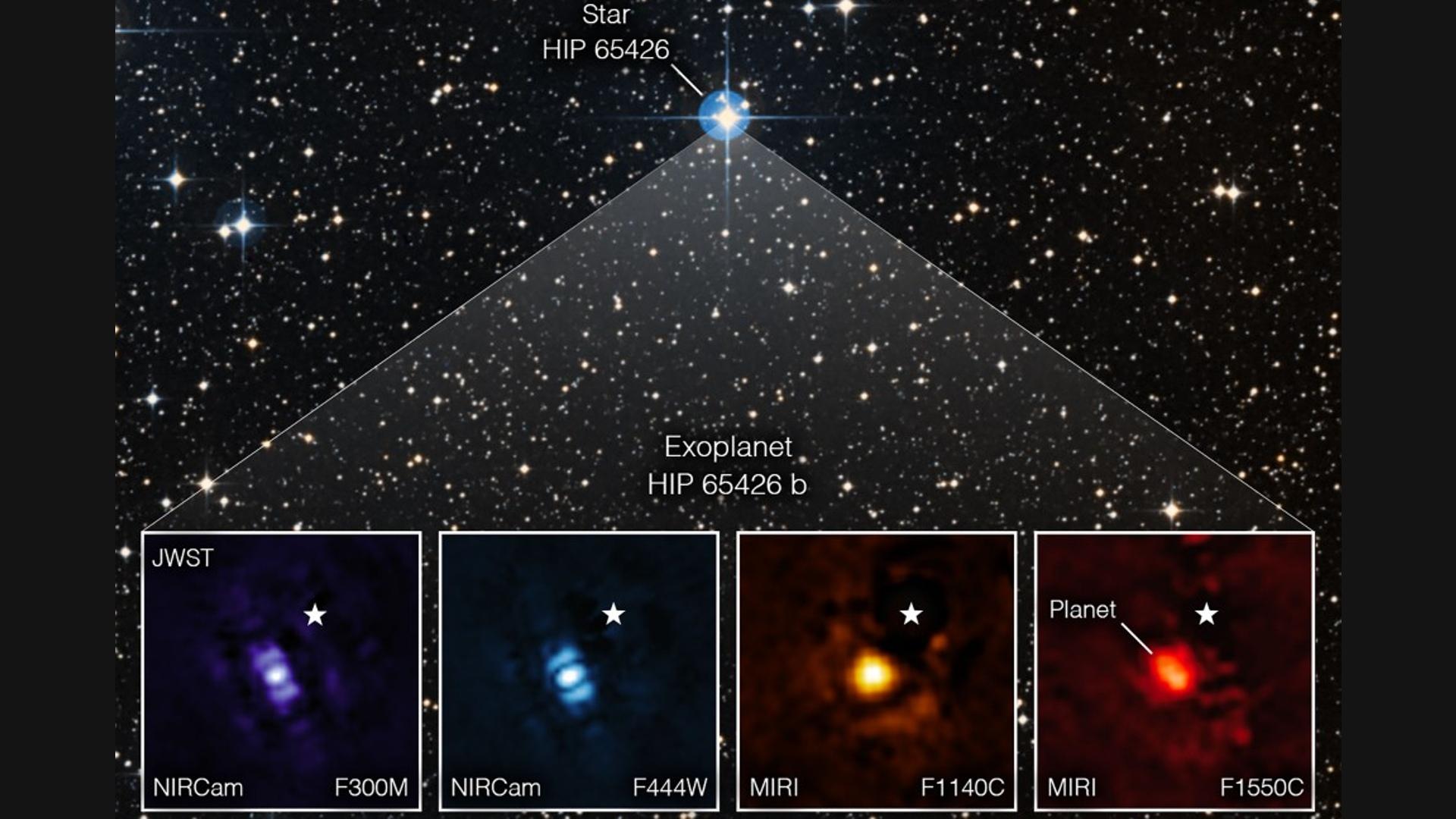

This image shows the exoplanet HIP 65426 b in different bands of infrared light, as seen from the James Webb Space Telescope. Purple shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 3 micrometers, blue shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 4.44 micrometers, yellow shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 11.4 micrometers and red shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 15.5 micrometers. (Credit: NASA/ESA/CSA, A Carter (UCSC), the ERS 1386 team and A. Pagan)

This image shows the exoplanet HIP 65426 b in different bands of infrared light, as seen from the James Webb Space Telescope. Purple shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 3 micrometers, blue shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 4.44 micrometers, yellow shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 11.4 micrometers and red shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 15.5 micrometers. (Credit: NASA/ESA/CSA, A Carter (UCSC), the ERS 1386 team and A. Pagan)

The images I’m looking at the moment, I’m seeing four different images in different colors. I know from the caption that I’m seeing the planet in different bands of infrared light, but explain to me what astronomers can learn from these images?

What we can do is basically measure the brightness of the planet at different wavelengths and one of the things you can do is add up the planet’s brightness at all the different wavelengths to kind of measure the total energy budget of the planet. Another thing we can do is look for wavelengths where the planet is slightly fainter than we expect compared to the other wavelengths. And if the planet is slightly fainter at one wavelength that kind of tells us that there might be some sort of absorption feature that could be due to molecular species in the atmospheric clouds in the atmosphere. That kinds of tells us what this planet is made out of. So we can use these images to understand what this planet looks like and what it’s made out of.

Given the power of Webb, could it be the instrument that actually allows us to detect life beyond the Earth? Not necessarily intelligent life but potentially signs of plant life because of what we can tell about an exoplanet’s atmosphere. Do you think that Webb is an instrument that will allow us to do that?

I think it has a small chance. It’s not a big chance. I think, you know, most of us aren’t holding our breath, but there are a few particular systems, the spectrograph mode, that may have a chance of seeing something…. I think that there’s only a few planets for which that may be possible. And obviously other folks in our community are working on things like that, but we’re not holding our breath waiting for that right now, just because I think the hopes are slim.

This is the first exoplanet that Webb has imaged. Presumably it won’t be the last. What will be some of the future targets that you’re likely to try and image?

I think our community, not just myself, but our community will probably try to image all of the known known planets that have been imaged before. We’ll try to image them using Webb at these wavelengths that are not accessible from the ground with the goal of really understanding what they’re made out of, how bright they are and understand how the giant planets forms. So I think planet formation and planet composition will be kind of key things that we will be going after with Webb — at least from my interests.