An outcrop of 400-million-year-old dolostone at Chicago’s Palmisano Park. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

An outcrop of 400-million-year-old dolostone at Chicago’s Palmisano Park. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

It only took 400 million years, but dolostone has finally been named Illinois’ official state rock.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed the declaration into law earlier this week, crediting a group of suburban Chicago elementary and middle school students for pushing the legislation through Springfield.

“You couldn’t have picked a rock that better represents Illinois,” Pritzker said.

Dolostone, which beat out sandstone and limestone for the honor, now joins the ranks of other Illinois symbols, including the white oak as the state tree, the cardinal as state bird, popcorn as state snack and cycling as state exercise.

Illinois residents are likely far more familiar with the rest of that list than they are with dolostone. Allow us to make the introduction.

WHAT IS DOLOSTONE?

Dolostone is the hard bedrock that lies underneath most of Illinois’ glacially-deposited soil, found closer to the surface in some places than others depending on erosion. It’s often referred to as dolomite, which is actually the mineral found in dolostone rock, and if that sounds confusing, well even some scientists use the terms interchangeably.

It doesn’t help dolostone’s case for naming rights that its most visible branding opportunity — Italy’s Dolomite Mountains (or Dolomite Alps) — are essentially mislabeled.

Italy's Dolomite Alps. (Flickr / puffin11k)

Italy's Dolomite Alps. (Flickr / puffin11k)

Here in Illinois, in the absence of any spectacular mountain-forming activity, dolostone is kind of like Midwesterners themselves: down to earth, sturdy and dependable.

But just because it isn’t colorful or flashy — “A rock only a mother lode could love,” joked one geologist — doesn’t mean dolostone doesn’t have a few tricks up its sleeve.

WHERE DOES IT COME FROM?

A recreation of a Silurian reef, at the Field Museum. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A recreation of a Silurian reef, at the Field Museum. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The most important thing to know about dolostone is that it formed in an ancient tropical ocean, during the Silurian period of the Paleozoic Era, some 400 million years ago.

So how did it end up in Illinois?

“If you run the clock backward, North America was at the equator,” said Scott Elrick, head of coal, bedrock geology and industrial minerals with the Illinois State Geological Survey. To draw a picture, he said, think of Illinois being the Bahamas or Florida Keys during the Silurian.

This sea harbored a massive underwater Silurian reef system — not one giant continuous reef but a string of reefs, maybe 10 miles apart, stretching up to what’s now Door County, Wisconsin. And it was teeming with life, said Paul Mayer, collection manager of fossil invertebrates at the Field Museum.

There would have been tabulate corals (now extinct), reef-building stromatoporoids (extinct sponges), brachiopods (kind of like clams or mussels), cephalopods, trilobites and meadows of plant-like animals called crinoids.

“This was the tropical hot spot,” said Mayer.

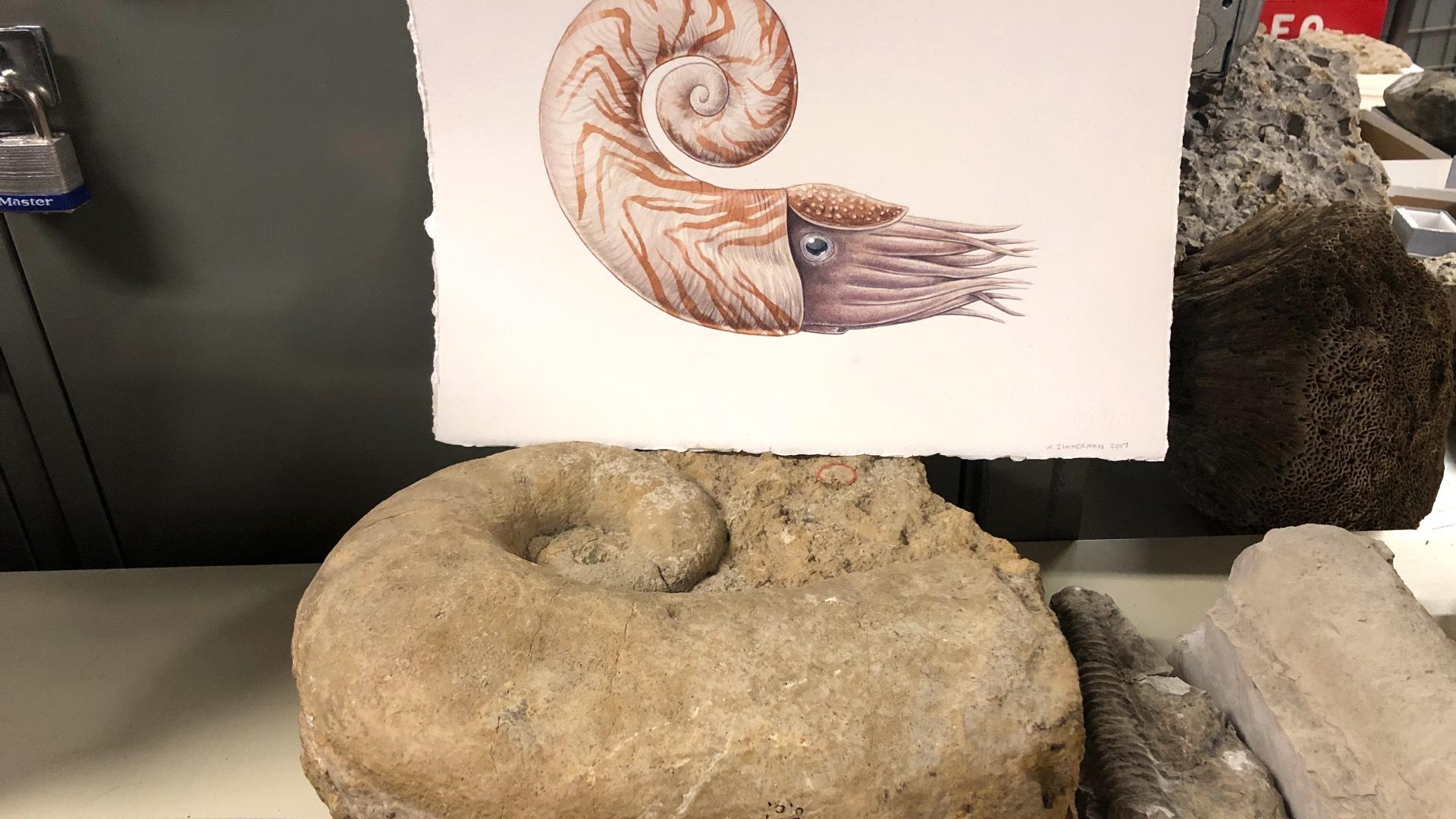

A Silurian fossil, in dolostone, in the Field Museum's collection, with a drawing of the creature as it appeared 400 million years ago. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A Silurian fossil, in dolostone, in the Field Museum's collection, with a drawing of the creature as it appeared 400 million years ago. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Now imagine the remains of all those creatures accumulating on the sea floor as piles and piles of shells. Over time, these piles became buried and compacted, a calcium carbonate mud hardening into rock. And that’s how limestone formed.

Wait, limestone? What happened to dolostone?

Dolostone starts as limestone, explained Melissa Pardi, curator of geology at the Illinois State Museum. No limestone, no dolostone.

Here’s what happens: When water containing magnesium flows through limestone, the magnesium in the water exchanges with the calcium in the rock. This process can occur either when the sediment is still soft or later, when the limestone has already hardened, Pardi said. This exchange, and the presence of magnesium, is what created dolostone.

Curiously, while limestone is still forming today in places like the Bahamas, where conditions resemble the Silurian stew, dolostone isn’t following suit.

“We don’t see it as much in younger rock. Why, what has changed?” said Pardi. “Scientists are actively researching. One thought is it has to do with microbial activity.”

Such is the challenge of the field of geology.

“I sometimes describe what (we) do as ‘a consensual hallucination of the past,’” Elrick said. There’s the observed evidence and then an attempt to imagine how and why it got there, constrained by science.

“It’s the incessant, ‘Why, why, why?’” he said.

WHAT’S IT USED FOR?

To call dolostone the foundational rock of Illinois is true both literally and figuratively.

It’s been heavily quarried throughout the state, originally for use as a building material. Illinois’ Old State Capitol in Springfield was constructed with creamy, buff-colored dolostone, and Joliet “limestone,” found in a number of prominent historic buildings, is actually dolostone, said Pardi. Maybe the new state designation will inspire people to call the rock what it really is, she said.

The historic Old State Capitol in Springfield, Ill., built with dolostone. (Google)

The historic Old State Capitol in Springfield, Ill., built with dolostone. (Google)

Today dolostone is most commonly quarried for crushed stone aggregate used in concrete.

“It’s so critical to the infrastructure of the state. Every place you see concrete is pulling from our dolostone resources,” said Elrick. “We couldn’t build what we do without it. For every 25 miles you have to transport aggregate, the cost doubles. Being able to obtain it locally is cheaper; the location of quarries is really important for the cost.”

It can be hard, even for a geologist, to wrap his brain around the notion that streets and sidewalks are paved with the remains of 400-million-year-old sea creatures.

“There’s this immense story hiding underneath our feet,” Elrick said.

WHY NO ‘SILURIAN PARK’?

Given its origins, dolostone is typically studded with fossils. So why isn’t Illinois famously known as “Silurian Park”?

For starters, there is a lot of the stuff. Four hundred million years from now, will anyone care about coming across the gazillionth zebra mussel fossil? Another issue is that the “dolomitization” process — limestone becoming dolostone — causes fossils to lose a lot of their detail.

And, frankly, a good portion of the state’s fossil record tells the story of tiny invertebrates instead of charismatic dinosaurs, a factor that has often overshadowed the state’s embarrassment of ancient riches. “People like things with eyes,” said the Field Museum’s Mayer.

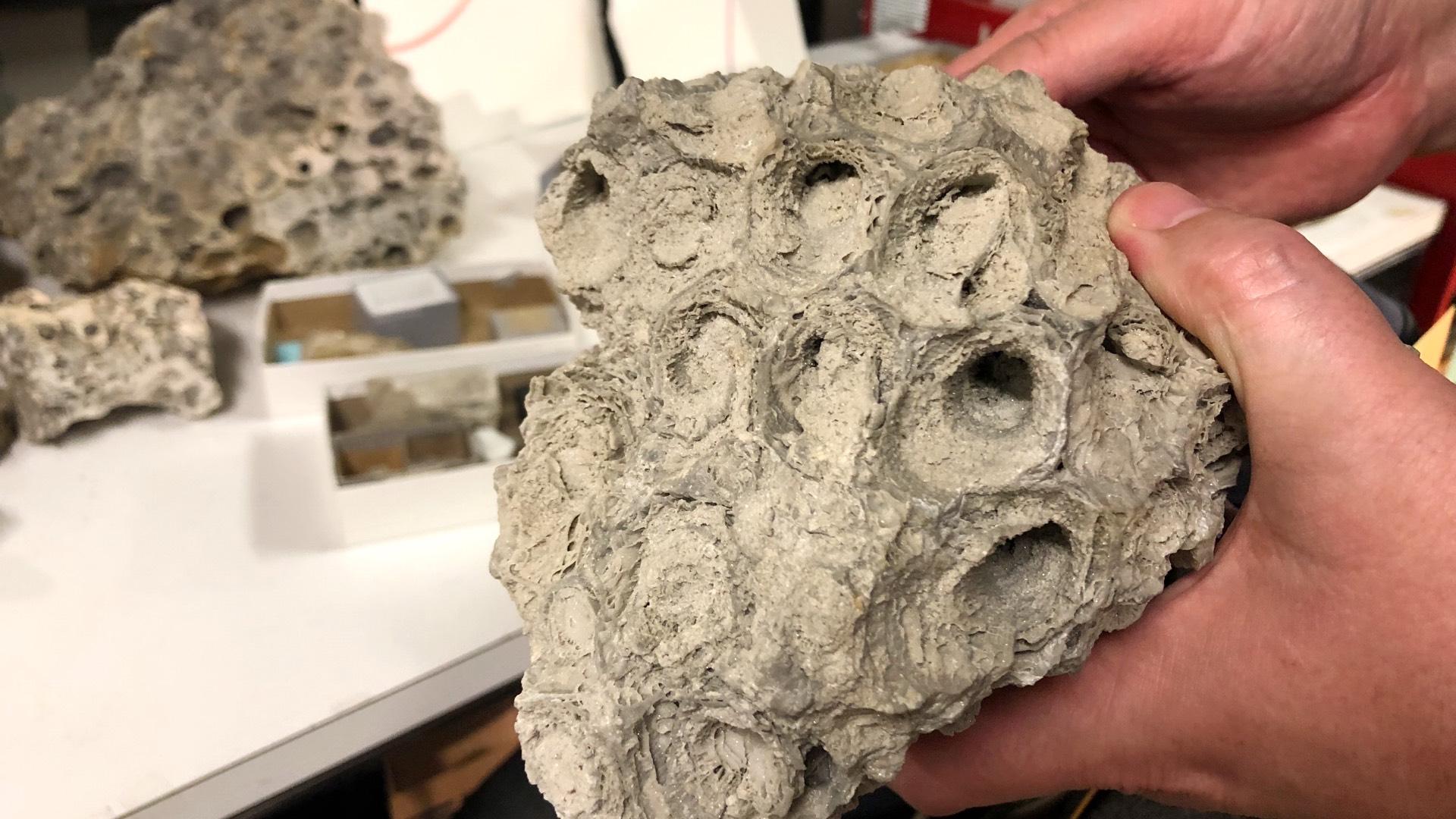

Dolostone Silurian reef fossil, from Thornton Quarry, in the Field Museum's collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Dolostone Silurian reef fossil, from Thornton Quarry, in the Field Museum's collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Still many a fascinating Silurian find has been brought to the surface — a number of them housed in the Field’s collection — just not by teams of researchers painstakingly exploring historic sites but rather during quarrying.

“In the old days, a lot of the quarrying was done by hand. Rich paleontologists would pay an extra dollar for fossils,” Mayer said.

When the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was dug, he said, loose mounds of rock were deposited along the sides of the channel as crews carved a trench through the dolostone bedrock. “You could climb the hills and search for fossils,” Mayer said.

A dolostone fossil of an ancient sponge, in the Field Museum's collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

A dolostone fossil of an ancient sponge, in the Field Museum's collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

To this day, quarries preserve some of the finest remnants of dolostone Silurian reef. A sizeable 300-foot-tall section is contained within Thornton Quarry, 25 miles south of Chicago, traversed by the Tri-State Tollway I-80/294. The reef isn’t part of the wildly popular twice-yearly tours of Thornton — there’s a two-year waiting list — because it’s now located in a section of the quarry that’s been turned over to the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District for use as a reservoir.

Most of the time the reservoir is fairly empty and the reef is visible, an MWRD spokesperson told WTTW News. Even if the reservoir were to be filled to its maximum volume, the top of the reef would rise above the water.

A more accessible, if less grand, Silurian dolostone outcrop exists in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, where a former quarry has been converted into the striking Palmisano Park. Sagawu Canyon in Lemont, site of the only natural canyon in Cook County, is another excellent example of exposed dolostone.

ROCK, MEET PRAIRIE

The extensive quarrying of dolostone means only a handful of places still exist in Illinois where rock and prairie find common ground in the form of what are known as dolomite prairies.

Dolomite prairies differ significantly from the iconic tallgrass expanses most people picture when they hear the word prairie, and that has everything to do with the presence of dolostone bedrock either at or extremely close to the surface. Where towering tallgrass plants need to sink their roots deep into the ground, the short grass plants associated with dolomite prairies can make do with far less.

“There might be cracks in the rock or a shallow layer of soil, like one to four inches,” said Kelly Mikenas, assistant professor of biology and director of the environmental studies program at Elmhurst University.

Species such as side-oats gamma grass, prairie smoke and native prickly pear cactus are well suited to dolomite prairie, she said, and she’s even found rare examples of a plant called quillwort growing in dolomite remnants.

“It reminds me of an air plant,” Mikenas said of quillwort. “You could imagine this tiny three-inch plant, there’s no way it would survive in tallgrass. They would get out-competed for light in tallgrass.”

Exposed dolostone at Chicago's Palmisano Park. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Exposed dolostone at Chicago's Palmisano Park. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Mikenas has been studying dolomite prairies to determine if this vanishing landscape of scrappy plants could represent the future of ecological conservation in an even harsher environment — Chicago’s urban rooftops.

The industry standard for green roofs is to plant a covering of sedum, which is drought tolerant and can survive in little soil. “But as for supporting urban biodiversity — birds, insects and pollinators — they fall short,” she said. “We’ve got these spaces as habitat, we could do better. We could support native wildlife, we could provide habitat for natives that only have these little pockets left.”

Classic tallgrass prairie plants wouldn’t work on a roof, given the soil limitations, which led Mikenas to wonder, “What if we take plants in dolomite prairies? Part of the work I did was to see if that plant community could be replicated on a green roof,” she said.

The answer was “yes.” Not only did they grow, they survived with little maintenance and also supported genetic diversity.

Now the challenge is to get developers to adopt this approach to green roofs.

“If there’s a demand for native plants, the industry will adjust,” Mikenas said, but first people have to know that’s even an option.

The green roof atop Chicago's City Hall has 300 species of plants, but “someone had to ask for that,” she said. “It’s not ‘package A’ or ‘B’ or even ‘C.’ But you can get it.”

In a sense, Illinois’ new state rock can be seen as the the link that binds together 400 million years of history.

We’ve come a long way from that ancient tropical ocean to the tops of Chicago’s modern skyscrapers. Through it all, dolostone’s story is still being written.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]