Do inmates in Illinois prisons and jails have a right to safety?

That’s the central question raised in a new publication written by former Cook County Department of Corrections Warden Nneka Jones Tapia.

In it, Jones Tapia makes the case for a more holistic health and safety vision for those in custody. The work comes after COVID ravaged through corrections facilities across the country.

Chicago Beyond released the “Do I Have the Right to Feel Safe” to provide guidance to criminal justice system stakeholders. Read the full report.

Answers have been edited for length.

How did your experience as a clinical psychologist and warden at Cook County Jail inform your vision of what a holistic criminal justice system could look like?

Nneka Jones Tapia: I think when I started in corrections and through my 10 years as warden, I really realized and saw firsthand the impact that the system had on people who were incarcerated, their families, as well as the staff. I mean I think I saw the overwhelming negative and damaging impact that the system had in the reverberating impact throughout the community.

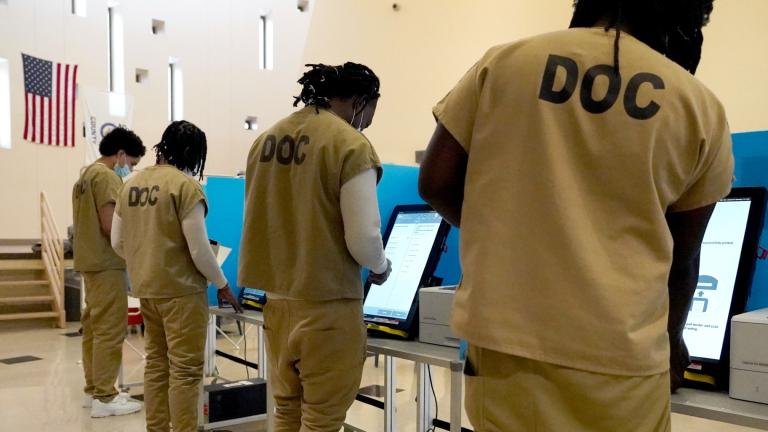

America incarcerates more people than any other country in the world. It seems to be a system that’s premised more on punishment than the possibility of rehabilitation. Do you think it’s fair to say that at this point, that approach has failed?

Jones Tapia: I think we’re long overdue to say that this approach to crime has failed. I think if we want to ensure the safety of everyone, we have to focus on creating the conditions that are going to actually produce positive behavior — and that’s not punishment and control.

What kind of toll does the current mass incarceration approach to crime take on both the incarcerated and those who work in correctional facilities? Particularly those inmates who may wait years simply to get to trial?

Jones Tapia: I would say that really the toll begins from the moment a person enters into the facility. There is a darkness that exists in correctional facilities and you feel that darkness as soon as you walk in, whether you’re a person incarcerated or a staff member. And so the longer that you are required to sit in that darkness, the more negative impact that it has.

What I saw during my tenure at Cook County was the longer that people awaited trial, the more likely they were to engage in negative behavior, again as an impact of sitting in this darkness. It’s not because they were a bad person, but because we had them in a horrendous environment and that’s not unique to the Cook County Jail. I don’t want to paint Cook County as being the only institution that holds people for a longer period of time or that is wrought with darkness — that’s every correctional institution. And because people sitting in there for longer periods of time are more likely to act out that impacts the staff.

We know that the American criminal justice system treats Black and white defendants differently. Talk to me a little bit about the racial aspect of this?

Jones Tapia: I think that what we see happening in jails and prisons is a reflection of how we in America have historically engaged with race. America tends to fear Black and Brown people and we have responded to that fear by trying to control Black and Brown bodies and trying to punish Black and Brown bodies.

We don’t have a Black criminality problem, (we have) a black exclusion problem. Black and Brown people have been excluded from the very resources and supports that we all know everyone needs in order to thrive. Employment, education, housing opportunities, mental health and physical health services. And so we have to think about our answer to this exclusion problem is not a system that will further exclude people, which is what jails and prisons do, but to think about how we can really nurture the innate positive attributes that exist within people. And we can only do that through connecting them with positive supports, through realizing and investing in the inherent strengths and the humanity that exists in all of us.

At this moment in time, do you think there is an appetite to change what the American correctional system looks like? Do you think there’s the appetite at this point to actually make fundamental change?

Jones Tapia: I think there is an appetite for change for the people who work in, and are confined by, these systems. I believe that the voices of those two groups in particular have to be put on a broader platform because there is also the

voices of people who believe that we should be tougher on crime. And they believe that jails and prisons are the antidote to the rise in crime that we see happening across the country. And so what Chicago Beyond has tried to do is just amplify the voices of people who are impacted by the system to say that while some people think that these systems work to create safety, they actually erode safety.

Give me a sense of how folks who actually work within the correctional system feel about the possibility of reform?

Jones Tapia: Almost everyone who works in the system has been exposed directly and indirectly to trauma and that trauma sits with them. It doesn’t come off when they take off their uniform when they get home to their families. They interact with people differently, their families, community members. And I think many people working in the system see that. One study found that almost a third of correctional officers have some PTSD and meet criteria for depression. Whereas in the general population, about 3-6% of people meet criteria for those diagnoses. And so the impact is real. You know, and I think the more that we give people who work in the system, the platform to really talk about the impact … the more that they want to be a part of that change. People who work in corrections have a life expectancy that’s 20 years lower than the general population. So they are literally dying because they work in these systems. And so they know that something has to change.

Tell me a little bit about the impact you see on the families of both those incarcerated and those working in correctional facilities?

Jones Tapia: I experienced it. I experienced that impact as a young girl visiting my father in the prison. It was something that without the appropriate support from my family and my community could have caused long-lasting negative impact. I saw it as an employee working in this system where families of people incarcerated would call me concerned about the welfare of their loved ones.

That anxiety that families experience when their loved one has been incarcerated impacts them in every area of life. The impact of these institutions, it doesn’t just occur for people who walk into those institutions or who sit in those institutions. One study recently found that close to 113 million Americans have an immediate family member or have had an immediate family member who has been incarcerated. I mean, you think about the impact of that in the grocery stores in our churches and our schools and our communities. People are sitting with that anxiety and have little space to talk about or to be a part of changing system that’s causing that anxiety.

What does a re-envisioned American justice system and correctional system look like?

Jones Tapia: It looks like empowerment of people who have been most impacted by the system. That’s the staff, that’s the people who are and have been incarcerated. That’s the families of these groups, that’s survivors of crime, that’s community organizations that are most impacted by incarceration. And it doesn’t look like control and punishment, instead it looks like centering the conditions that are going to help people to thrive. And leaving space for continuous iterations of what that could be. It’s not a check the box exercise. It is something that we have to continuously work towards.

What kind of response have you had to your new holistic vision for the correctional system from people who work within it?

Jones Tapia: We created this vision in partnership with people who work in the system, people who have been incarcerated in the system, as well as survivors of crime and current and former correctional administrators. Almost 100 people have lent their voice to this vision. And while we have divergent pathways of how we have gotten here, we all agree that what we are doing through mass incarceration and through divestment in communities is not working and that we collectively have to think about universal healing and supports for our whole communities. If we truly want to experience safety, we have to invest in the people and the communities that they come from.