Ossie Cloe takes work day by day, and sometimes hour by hour. She’s an intensive care unit nurse at HSHS St. John’s Hospital in Springfield, where she’s been working directly with COVID-19 patients throughout the pandemic.

“If we think too far into the future, the anxiety we feel becomes overwhelming,” Cloe said. “We’re scared before we even start.”

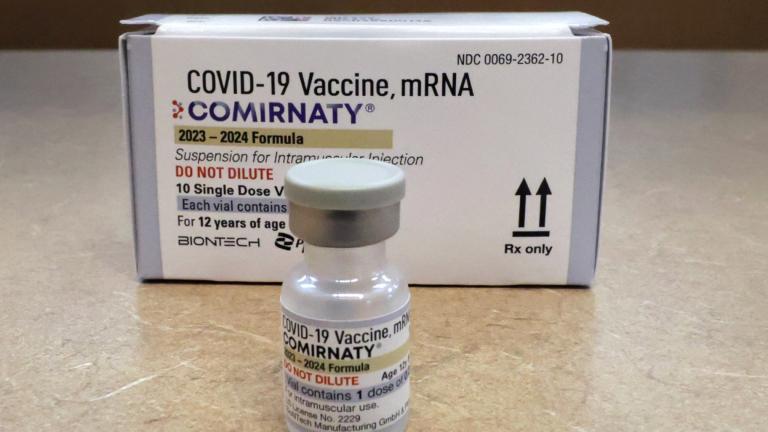

Earlier this year, as COVID-19 vaccines rolled out and Cloe’s hospital began closing down its extra ICUs, she felt hopeful that the worst of the pandemic had passed. Now, as infections surge once more, Cloe says it’s disheartening to have to “do this all over again.”

Eighteen months into the pandemic, Cloe and other health care workers are reporting feelings of burnout. Some say they are nearing their breaking point as COVID-19 surges again in Illinois and across the country.

A roller coaster of emotions

“The pandemic as a whole is exhausting. Not just physically, but mentally and emotionally,” said Ashley Lachowicz, a night shift supervisor and respiratory therapist at Rush University Medical Center. Health care workers can go through several emotions within one shift, from grief and sadness to fear and numbness.

Brady Scott says he didn’t think the pandemic would still be impacting hospitals like it is this far into the pandemic. He’s a respiratory therapist at Rush Medical Center and director of clinical education for respiratory care at Rush University.

“As much as we appreciate people giving us credit for being on the front lines, I don’t know that we are on the front line,” Scott said. “When you come to the ICU that’s the end of the line. You’re on the front line, the public, you’re on the front line of the pandemic. You help us keep the hospital not so full.”

Dr. J. C. Michel said burnout from the latest COVID-19 surge is particularly acute because it feels preventable. He’s director of critical care at OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria and an intensive care doctor.

“Many who are dying are not vaccinated,” Michel said. “If they had been, we can’t help but wonder if lives would have been saved, if beds would have been open for other people to get help. It feels unnecessary. It feels different. There is a sense that it might not have needed to be like this.”

Lupe Perez is a community nurse in Chicago and a member of the Illinois chapter of the National Association of Hispanic Nurses. She says she’s worried about what the fall and winter months could bring.

“I’m very concerned because even though our state is trying to do a good job on mandating masks, trying to educate the public about vaccination, I’m still worried because we are still seeing cases, people are still getting very sick,” Perez said.

Not only is she concerned about COVID-19, but she’s also worried about other illnesses that come around each winter, like the flu and respiratory viruses.

Cloe, the ICU nurse in Springfield, says the pandemic has been one of the most challenging times in her career. As an ICU nurse, Cloe said she is “no stranger to death.” But death during the pandemic is different, she said. It has taken the dignity out of it. Patients die alone, without their families.

“Sometimes you’re the only person with them,” Cloe said. “In most cases you are the last face a person will see. It can change you. The room is quiet, while it is bustling outside the door with other patients. It’s hard to put into words.”

Contact Marissa Nelson: @ByMarissaNelson | 773-509-5368 | [email protected]