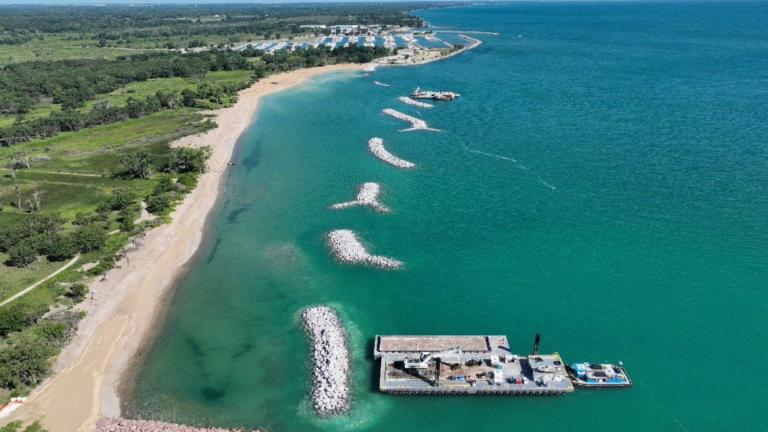

Lake Michigan. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Lake Michigan. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

When it comes to what scientists know about the effects of climate change on the Great Lakes, research to date has only scratched the surface.

“There have been studies all over the world looking at surface temperatures (of lakes) and, at least in summer, we see a warming trend,” said Craig Stow, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.

But for big lakes, hundreds of feet deep, what’s happening on the surface doesn’t have as much relevance as it does for shallower bodies of water, Stow said.

“If it’s only the surface that’s warming, that isn’t necessarily a very profound effect” on big lakes, he said.

To interpret climate impacts on the planet’s largest lakes — the top 10 of which hold 84% of earth’s non-frozen surface freshwater — the missing piece has been information about subsurface temperatures.

Now we have a glimpse into the murky depths.

A string of high-tech thermometers placed in southern Lake Michigan — the world’s fourth-largest lake — has, for 30 years, taken hourly temperature measurements, as far down as 150 meters, well below the 10-20 meters of what’s considered the lake’s surface.

Stow was among a team of NOAA-GLERL scientists, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Michigan and University of Toledo, who analyzed this data, and the results of their study were recently published in the journal Nature Communications. What they found: Lake Michigan’s deep water temperatures are rising too.

“The fact that we can see this now, down to nearly the bottom of Lake Michigan, in well over 300 feet of water, indicates a major change. This is a large effect, not just something superficial,” said Stow.

(Pixabay)

(Pixabay)

Lake Michigan is what’s known as a dimictic lake. That means its water column mixes surface-to-bottom twice a year — once in the fall and again in the spring.

The process is commonly referred to as the lake “turning over,” Stow said, but it’s a mistake to think of this as a “flipping.” Rather, the mixing takes place gradually over the course of several weeks, he said.

At some point, the mixing stops, and the lake settles into layers of warm and cold, becoming stratified until the next seasonal shift. In the fall, mixing is triggered by cooler air, and the reverse is true for spring.

“What seems to be happening is that the mixing process that occurs into the winter, beginning in the fall, is coming later and is probably more extended now. So we may never actually get that wintertime stratification, the layering surface-to-bottom set-up again,” Stow said. “We’ll still see mixing at the end of summer. It’s that mixing that occurs in the spring that we may lose.”

Because the mixing process recycles dissolved oxygen and nutrients throughout the lake, a switch to a single turning over would dramatically alter Lake Michigan’s ecology.

“The fish, the phytoplankton, the food web that exists there developed a life history over thousands of years, based on the lake the way it’s been up to now. And if that changes, it’s going to disrupt things in ways that are difficult to predict,” said Stow.

Among the potential scenarios: fish die-offs due to oxygen deficits and shifts in dominant species.

“The other thing to remember is this isn’t the only change the lake’s experiencing. It’s still feeling the effects of the invasive mussels and a number of other invasive species,” Stow said. “All of these things are going on at the same time. Think of it as a really badly designed experiment.”

Though it would be fair to assume that other large lakes are experiencing similar changes, it’s impossible to know for sure because the type of information gathered on Lake Michigan isn’t available anywhere else.

It was incredible foresight to have placed sensors in Lake Michigan 30 years ago, Stow said, when concerns about climate change were just beginning to bubble up. (Sensors were placed in Lake Huron seven to eight years ago, he said.) Decades down the road, the investment in the project has paid off by giving scientists a clear picture of changes over time.

“Long-term data in this business are just about the most valuable thing we can have. The problem is, when budgets get tight they’re one of the easiest things to discontinue. There were times when somebody had to step up and fight for continuing this project,” said Stow. “It would be useful to have a network of these sensors across the Great Lakes. But data aren’t free.”

While the NOAA-GLERL study has filled a gap in the climate change narrative, how this story ends is still anyone’s guess.

Stow said he believes the warming trend in subsurface Lake Michigan is “probably reversible,” but even with serious mitigations in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, that reversal will take time, and there’s no undoing some of the changes.

“If it does reverse course … that doesn’t mean that it’s going to return to the same state that it was in before this process started,” Stow said. “The lake today is related to what it was yesterday and the day before. You go through enough days, and you can’t go back in exactly the same way.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]