(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

Serving the homeless has become a very high-risk job in the era of COVID-19.

That’s how Anne Holcomb describes it. She works as the manager of facilities and resources at Ujima Village Homeless Youth Shelter on Chicago’s South Side.

“We may not be wearing full PPE, dealing with people who are dying, but we put ourselves in a very high-risk situation to deal with a high-risk population that’s not the healthiest, and provide things they need to survive,” she said.

A year ago, as people across the state watched news about the virus with increasing alarm and adjusted to the governor’s initial stay-at-home order, organizations like Ujima Village had to balance their work serving people in need with the goal of keeping their staff members safe.

For many organizations serving the homeless, that meant pausing street outreach programs and in-person services, relying instead on phone calls and emails.

But in the midst of state-enforced restrictions and closures, Ujima doubled its operating hours. Before the pandemic, it was open for 12 hours overnight. Now, it operates around the clock.

That change came at the request of city officials, Holcomb said. And the timing was rough.

“When we went immediately to 24 hours, three of my regular staff were in quarantine, (and) the next week it was five in quarantine,” Holcomb said. “That was more than half my 12-hour staff in quarantine.”

To fill that staffing void, employees worked overtime. Holcomb herself embarked on 20-hour days and slept several nights at the shelter on an inflatable bed in a storage room.

“It was rough. I didn’t have a day off from mid-March until June. I was working seven days a week,” Holcomb said. “I always managed to give my staff at least one day off, but many worked (six days a week) on the regular.”

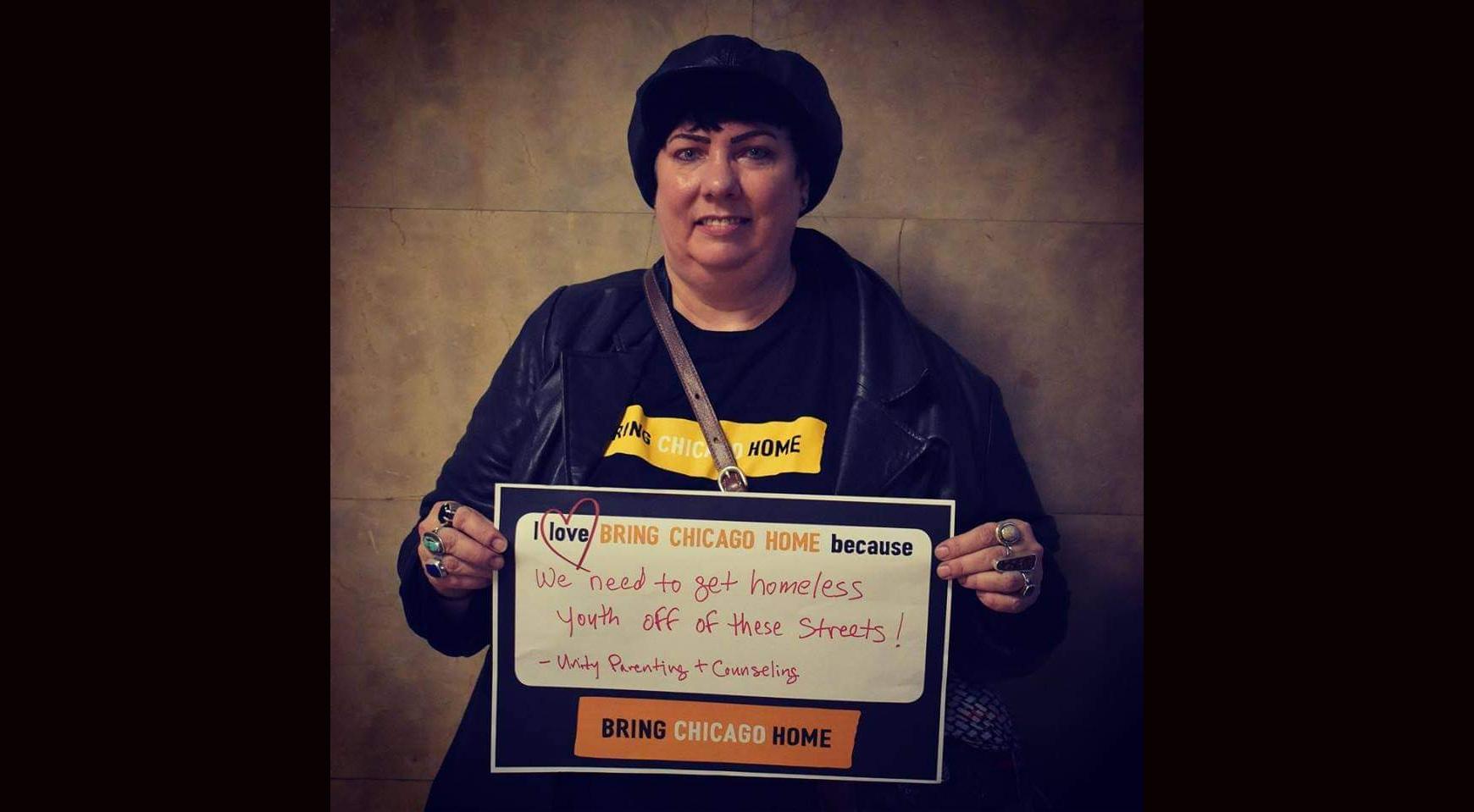

Anne Holcomb, manager of facilities and resources at Ujima Village Homeless Youth Shelter, participates in a demonstration at City Hall before the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. (Credit: The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless)

Anne Holcomb, manager of facilities and resources at Ujima Village Homeless Youth Shelter, participates in a demonstration at City Hall before the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. (Credit: The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless)

Expanding its hours also meant Ujima needed to provide lunch in addition to breakfast and dinner – a tall order, Holcomb said.

“We don’t have a kitchen or food license, so we can’t cook on site, which is fine most of the time but it was a struggle because of the short notice to begin providing lunches and the nature of the emergency,” Holcomb said.

She had to take matters into her own hands, heading to the grocery store. But even that was different.

“A lot of stores were closed,” she said. “I remember going to Walmart on 83rd and standing in line for three hours.” Once inside, another shopper took a case of ramen noodles out of her cart. “She grabs the case and says, ‘I’m feeding a family of five.’ And I say, ‘I’m feeding a shelter of 15,’ and she let go and walked away. … A woman was trying to fight me for ramen noodles.”

The fight for supplies didn’t end there. Holcomb, who experienced homelessness herself while in college, struggled to stock up on paper towels and toilet paper, items that were subject to purchase limits. “A couple staff brought toilet paper from the house, myself included, and paper towels,” Holcomb said.

‘We had to rethink and reconfigure everything’

Shelters in Illinois weren’t forced to close at any point over the past year, but — like everything else — they had to be modified in order to operate safely.

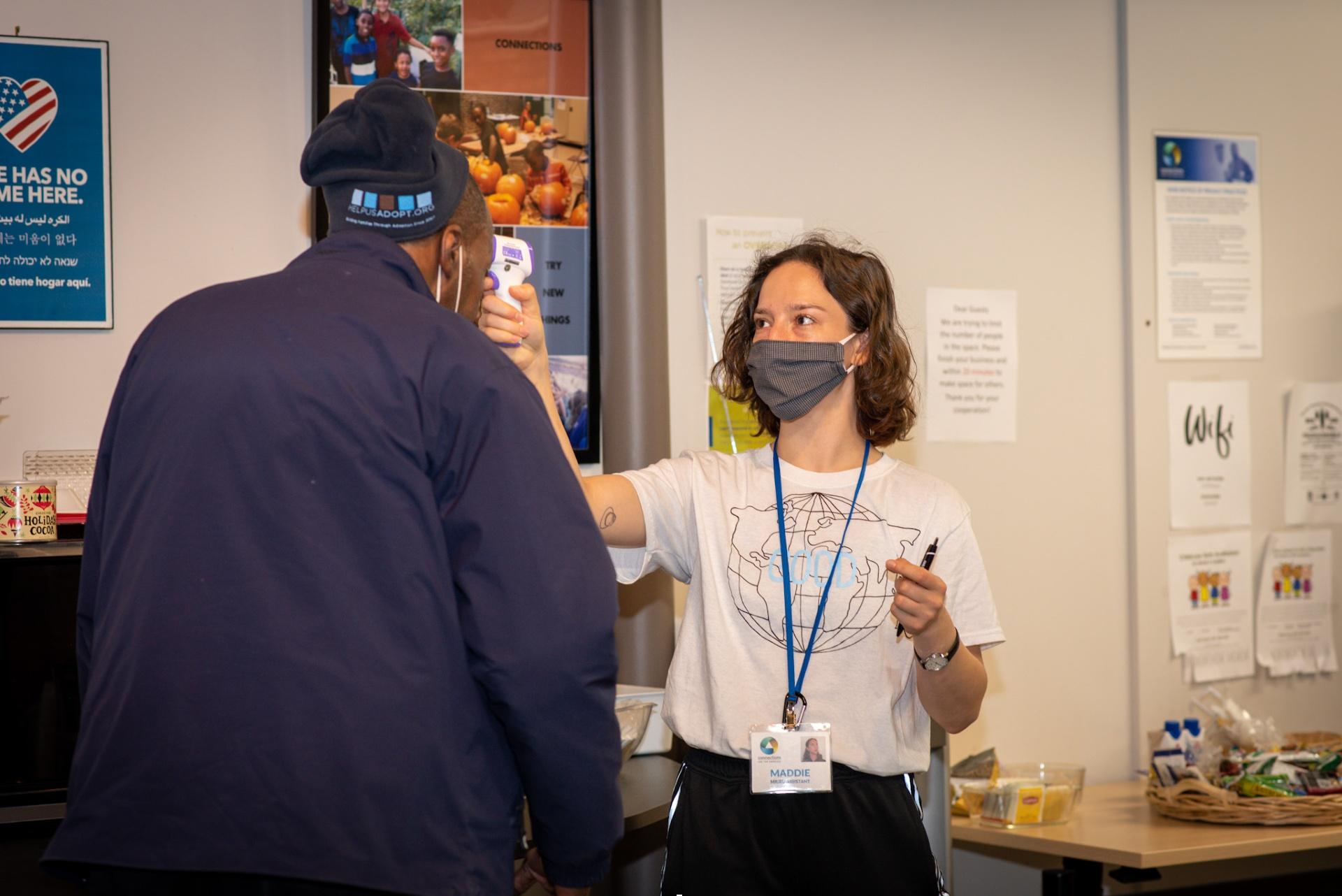

A staff member at Connections for the Homeless takes a person’s temperature. (Credit: Hex Hernandez Photography)

A staff member at Connections for the Homeless takes a person’s temperature. (Credit: Hex Hernandez Photography)

“One of the biggest things we provide for people on the streets is respite,” said Betty Bogg, executive director of Connections for the Homeless, which, prior to March 2020, operated an 18-bed overnight shelter for men in Evanston. But when the pandemic hit, offering a shared space for groups to rest and get some relief wasn’t possible. “We were operating out of a church basement with beds that were very close together,” Bogg said. “We had to rethink and reconfigure everything we did.”

Connections shuttered its shelter because it was too small to safely distance clients (it has since reopened in a larger space), but a unique partnership allowed the organization to expand its client base.

“We realized we could shelter people in hotels,” Bogg said. “Hotels were empty, so we embarked on a massive sheltering program over the spring and summer of 2020.”

The hotel partnership allowed the organization to provide shelter to women and families. “We have approximately 80 beds of shelter for men, women and children, and families in local hotels. That’s amazing,” Bogg said.

‘A state of fear’

After working from home for several weeks last year and acquiring personal protective equipment, the staff at Heartland Alliance Health, which has locations in Uptown, Englewood and on the Near West Side, resumed in-person services and street outreach.

“The coronavirus had me in a state of fear,” said Mark Lightfoot, pictured, who is a senior mental health worker at Heartland. (Credit: Heartland Alliance Health)

“The coronavirus had me in a state of fear,” said Mark Lightfoot, pictured, who is a senior mental health worker at Heartland. (Credit: Heartland Alliance Health)

“In the beginning, I was gloved, masked and I was disinfected heavily just because of the overall fear,” said Mark Lightfoot, a senior mental health worker at Heartland who has been meeting with people experiencing homelessness during most of the past year. “The coronavirus had me in a state of fear,” he said, but he wasn’t willing to stop working with clients.

Lightfoot (no relation to Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot) wasn’t the only Heartland staffer who feared catching the virus.

His colleague Augustus Sanford, who is a single parent, shared his concerns. “If something happens to me, who’s going to raise my son? The fear was definitely there,” Sanford said.

Masks and social distancing are meant to alleviate some of those concerns, but they can present challenges.

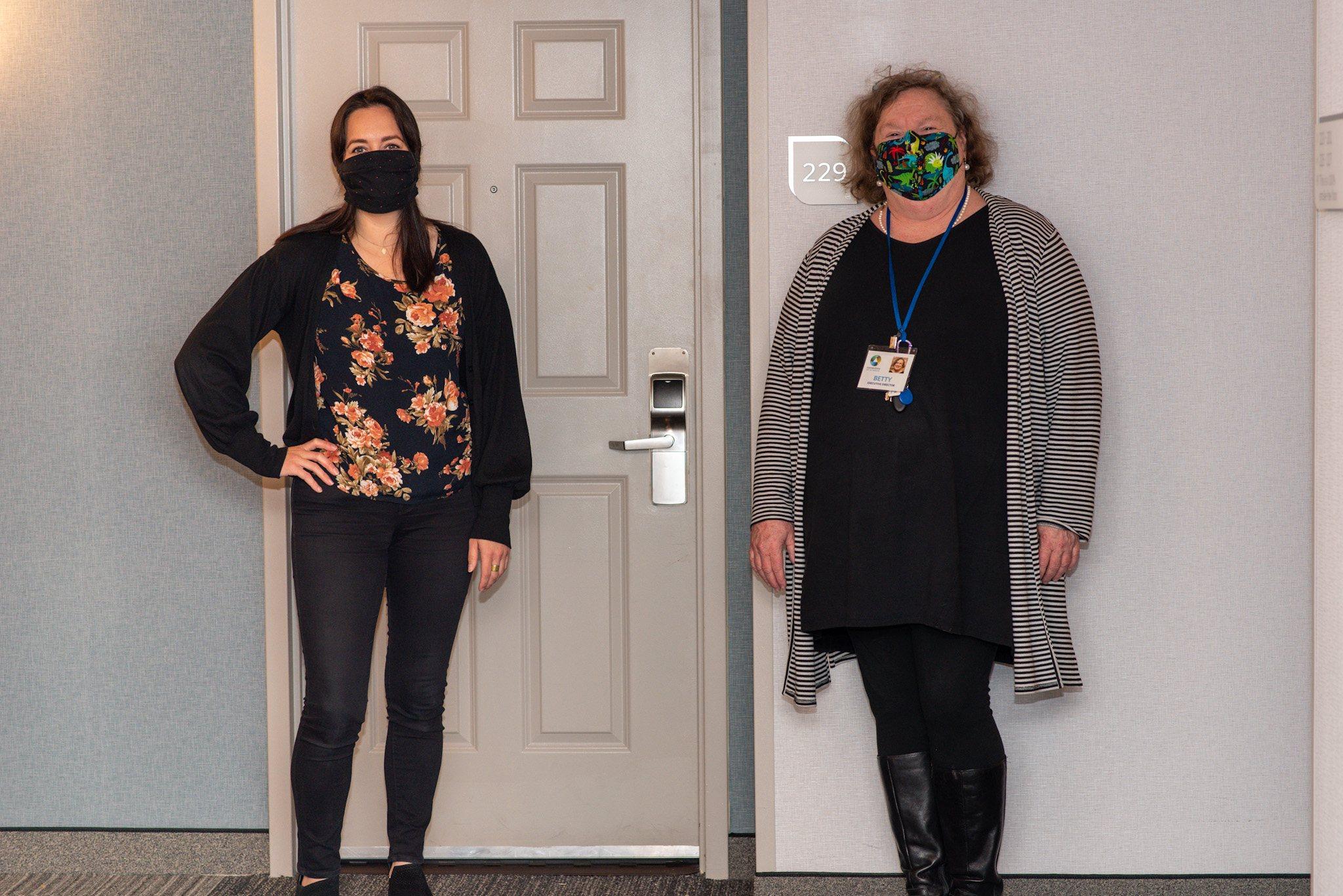

Jennifer Kouba, left, poses for a photo with Betty Bogg. Both work at Connections for the Homeless. (Credit: Hex Hernandez Photography)

Jennifer Kouba, left, poses for a photo with Betty Bogg. Both work at Connections for the Homeless. (Credit: Hex Hernandez Photography)

“For us to be good at our jobs we have to develop relationships with people,” Bogg said. “Doing that with masks on at 6 feet away it’s very difficult. … The things that make you really good at working in the homeless services arena makes it very dangerous for you if you want to hug someone or sit next to them to fill out a form.”

Staff at Heartland have developed ways to overcome those challenges. Lightfoot says he uses humor. Sanford says he reminds clients the current situation is temporary.

Daphne Riley, another senior mental health worker at Heartland, says she tries extra hard to be positive. “I try to make sure when they call I’m not grumpy. I’m always in a good mood,” she said.

Educating the public

Social service agencies are now facing another challenge: educating the people they serve about the COVID-19 vaccine, with the goal of getting them vaccinated.

Under the city’s vaccination plan, residents of homeless shelters and women’s shelters are among those eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Lightfoot, who is now fully vaccinated, has been part of those efforts.

“We talk about our experiences with the vaccine … and how we feel like we’re participating in the solution as opposed to the fear and the problem,” he said.

Members of Heartland Alliance Health’s outreach team. (Credit: Heartland Alliance Health)

Members of Heartland Alliance Health’s outreach team. (Credit: Heartland Alliance Health)

Heartland, whose staff has been trained to administer the vaccine, recently visited Ujima to vaccinate staff and residents. Holcomb, who is fully vaccinated, said none of the youth elected to get a vaccine shot. “We have one (young client) thinking about it because she has asthma,” Holcomb said. “The good thing is when they come back in a couple weeks they’re actually going to try again.”

Public education about the vaccine is vital, Holcomb says. She talks about her own experiences with the COVID-19 vaccine to illustrate that it’s safe, but she says youth need role models who look like them.

“For them to really buy into the vaccine, I think (if) someone who looks like the youth who’s African American, who’s youngish would come to the shelter and sit down and talk to them, I think they’d get a lot more buy-in,” she said.

Ultimately, she says, hospital workers deserve recognition as heroes. But they aren’t alone.

“There are other heroes out there still doing street outreach. There’s few things more important, especially in this climate, than having a roof over your head.”

Contact Kristen Thometz: @kristenthometz | (773) 509-5452 | [email protected]

This story is a part of the Solving for Chicago collaborative effort by newsrooms to cover the workers deemed “essential” during COVID-19 and how the pandemic is reshaping work and employment.

This story is a part of the Solving for Chicago collaborative effort by newsrooms to cover the workers deemed “essential” during COVID-19 and how the pandemic is reshaping work and employment.

It is a project of the Local Media Foundation with support from the Google News Initiative and the Solutions Journalism Network. The 19 partners span print, digital and broadcasting and include WBEZ, WTTW, the Chicago Reader, the Chicago Defender, La Raza, Shaw Media, Block Club Chicago, Borderless Magazine, the South Side Weekly, Injustice Watch, Austin Weekly News, Wednesday Journal, Forest Park Review, Riverside Brookfield Landmark, Windy City Times, the Hyde Park Herald, Inside Publications, Loop North News and Chicago Music Guide.