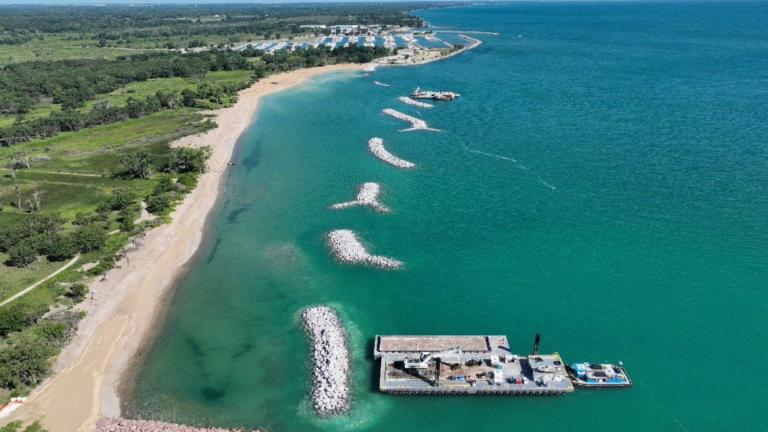

(Roman Boed / Flickr)

(Roman Boed / Flickr)

Rising sea levels pose a serious threat to cities like Miami, Tokyo, London and New York, but Chicago, despite its inland location, faces perhaps even greater peril from the effects of climate change, according to Dan Egan, author of “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes.”

Speaking Wednesday evening to a standing room-only crowd at the Harold Washington Library as part of One Book, One Chicago programming, Egan declared that “the [Great] Lakes are uniquely vulnerable to climate change. Chicago is vulnerable to a degree I don’t think other coastal cities are.”

The city’s counterparts on the Atlantic or Pacific, Egan explained, need to plan for water level shifts moving in one direction: upward. But in Chicago, “You’re not just dealing with high water, you’re dealing with low water,” he said.

At the point when Egan was writing his book, which synthesizes a decade of his reporting on the lakes for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Lake Michigan was at a near record low. In 2020, it’s at a near record high.

“In the past, it would take a quarter-century to go from low to high. We just did it in five years,” Egan said.

Going back to the 1840s, Lake Michigan has reliably peaked or bottomed out within 3 feet of an average level, for a total 6-foot swing. “Chicago was built on that assumption, so was Milwaukee,” said Egan.

The new norm could be 5-foot variations, for a 10-foot swing, he said, and that’s cause for alarm.

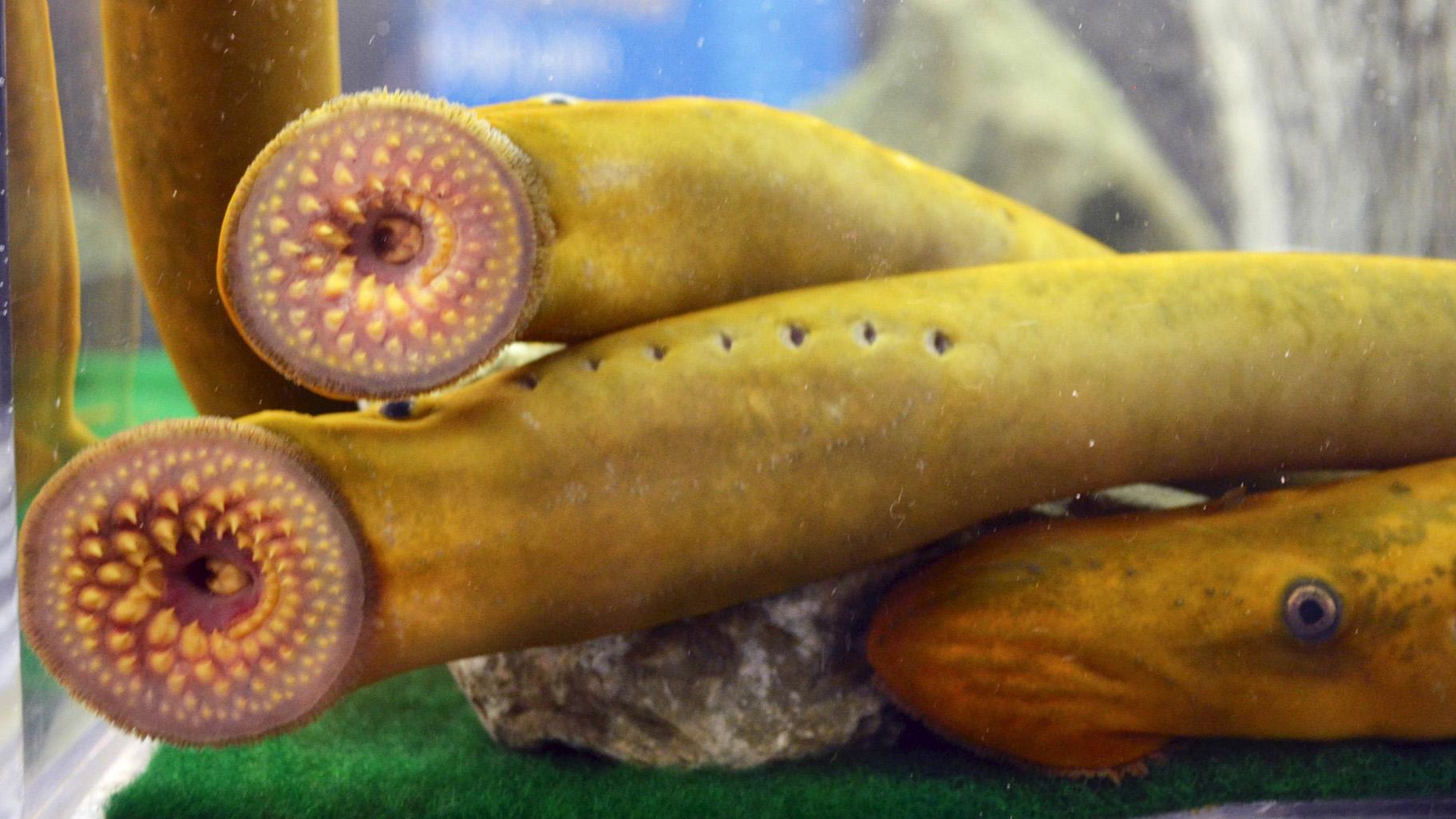

Invasive sea lampreys arrived in the Great Lakes via a door opened by the Saint Lawrence Seaway. (USFWS Midwest Region / Flickr)

Invasive sea lampreys arrived in the Great Lakes via a door opened by the Saint Lawrence Seaway. (USFWS Midwest Region / Flickr)

More than 30 million people live within the Great Lakes basin, and increasing their “Great Lakes literacy” is paramount in order for communities to make informed decisions about how to safeguard this resource, Egan said.

His book outlines numerous pivotal moments in which choices were made without fully contemplating the consequences or future-proofing the plan. The Saint Lawrence Seaway, for example, which was built to create a shipping lane connecting the lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, has been a disaster on numerous fronts.

“They just didn’t think a couple of steps ahead,” said Egan, including not taking into account that the waterway would ice over, rendering it impassable several months out of the year. More notably, the Seaway opened the door to invasive species that Niagara Falls had previously thwarted, among them the sea lamprey, which decimated the lakes’ native trout population. Ocean-going vessels also brought along hitchhikers, most infamously zebra and quagga mussels, which continue to devastate the lakes’ ecosystem.

Though the lampreys have largely been brought under control (but still cost Great Lakes states $20 million annually in poison, according to Egan), the mussels persist unabated. Too lax shipping regulations mean new invaders – or as Egan calls them, “biological pollution” – are still getting a free ride into this precious reserve of freshwater.

“We could be more tough with the overseas shipping industry,” said Egan. “The lakes don’t belong to the shipping industry, they belong to everybody.”

Mining along the lakes and projects like the Enbridge Line 5, a Canadian company’s oil pipeline that runs under the Straits of Mackinac, need to be reviewed with an eye toward what’s best for the health of the lakes and the creatures, human and otherwise, that depend on them, he said.

“That Line 5, if it fails, it’s going to make a mess the likes of which nobody’s seen. We should find another way to move that oil,” Egan said. Comparing a potential pipeline leak to the Exxon Valdez spill, which dumped 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, Egan noted: “We weren’t drinking that [Valdez] water. Forty million people drink Great Lakes water. That’s where we should start.”

![Author Dan Egan signs copies "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" at a One Book One Chicago event. [WTTW/Patty Wetli] Author Dan Egan signs copies "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" at a One Book One Chicago event. [WTTW/Patty Wetli]](/sites/default/files/styles/full/public/article/image-non-gallery/DanEgan_PattyWetli.jpg?itok=kV4okbCf) Author Dan Egan signs copies "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" at a One Book One Chicago event. [WTTW/Patty Wetli]

Author Dan Egan signs copies "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" at a One Book One Chicago event. [WTTW/Patty Wetli]

Furthering the work collected in his first book, Egan is in the midst of writing a second, this one focused on the effect phosphorous has had on the lakes. In recent years, Lake Erie has borne the most visible and dramatic consequences of agricultural runoff containing phosphorous, sprouting vivid green algae blooms that in 2014 left 500,000 Toledoans without access to safe drinking water.

Now that we have an understanding of the ways in which the lakes have become “out of whack” due to human intervention, Egan said, we have a responsibility to treat them with the respect they’re due.

Chicago Public Library’s One Book, One Chicago theme is “Season for Change.” Programs run through the end of February and include film screenings, discussion groups and art exhibits. Events culminate with a Feb. 20 appearance by Elizabeth Kolbert, author of the One Book selection, “The Sixth Extinction.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]