An underappreciated Chicago-born artist is getting a rare show at the Art Institute of Chicago. On the 100th anniversary of his birth, Charles White is being recognized with the first major retrospective of his work since 1982.

Chicago Tonight was there on opening day.

TRANSCRIPT

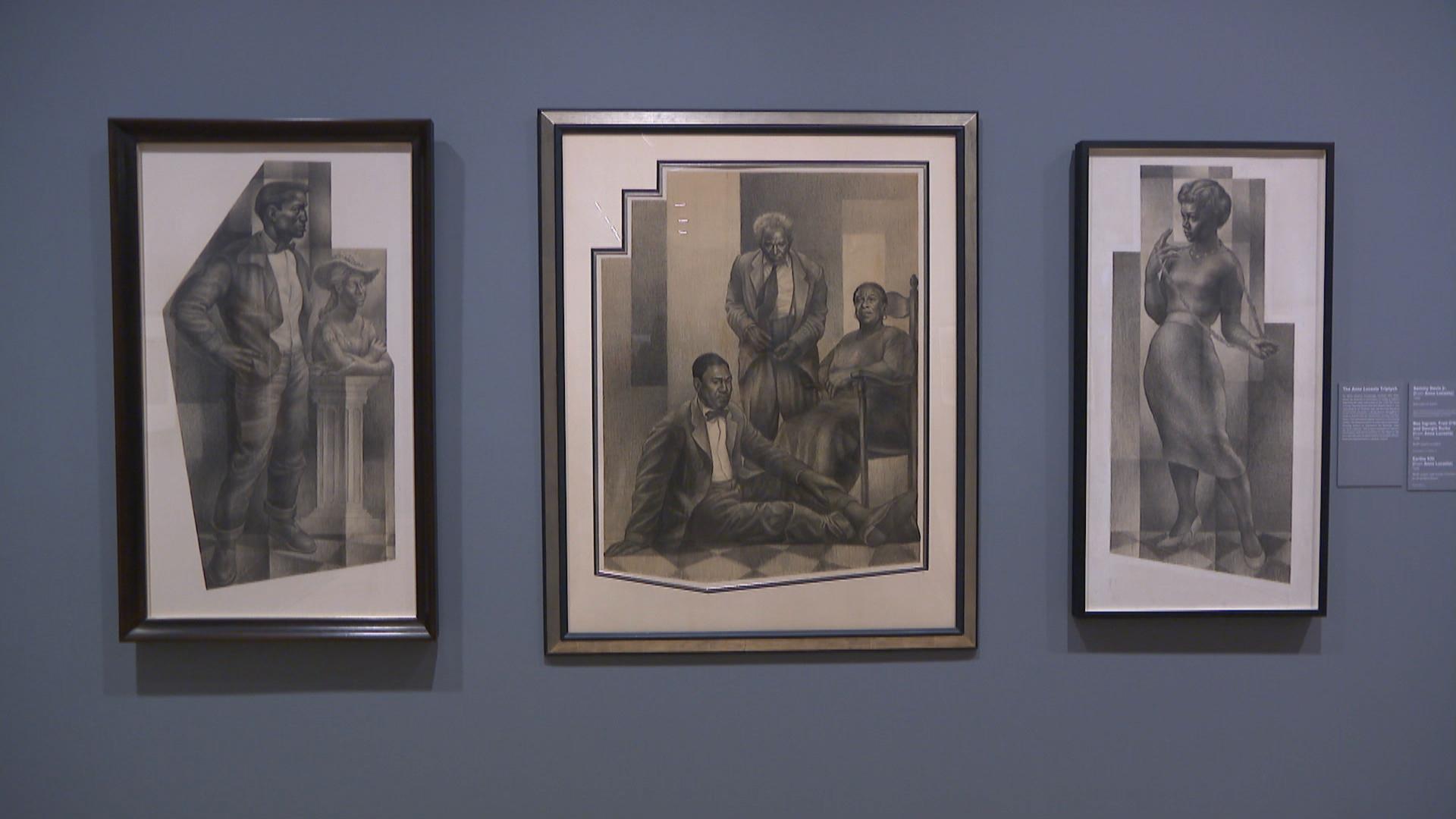

Brandis Friedman: You’ll see famous faces like the great blues singer Bessie Smith, Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass.

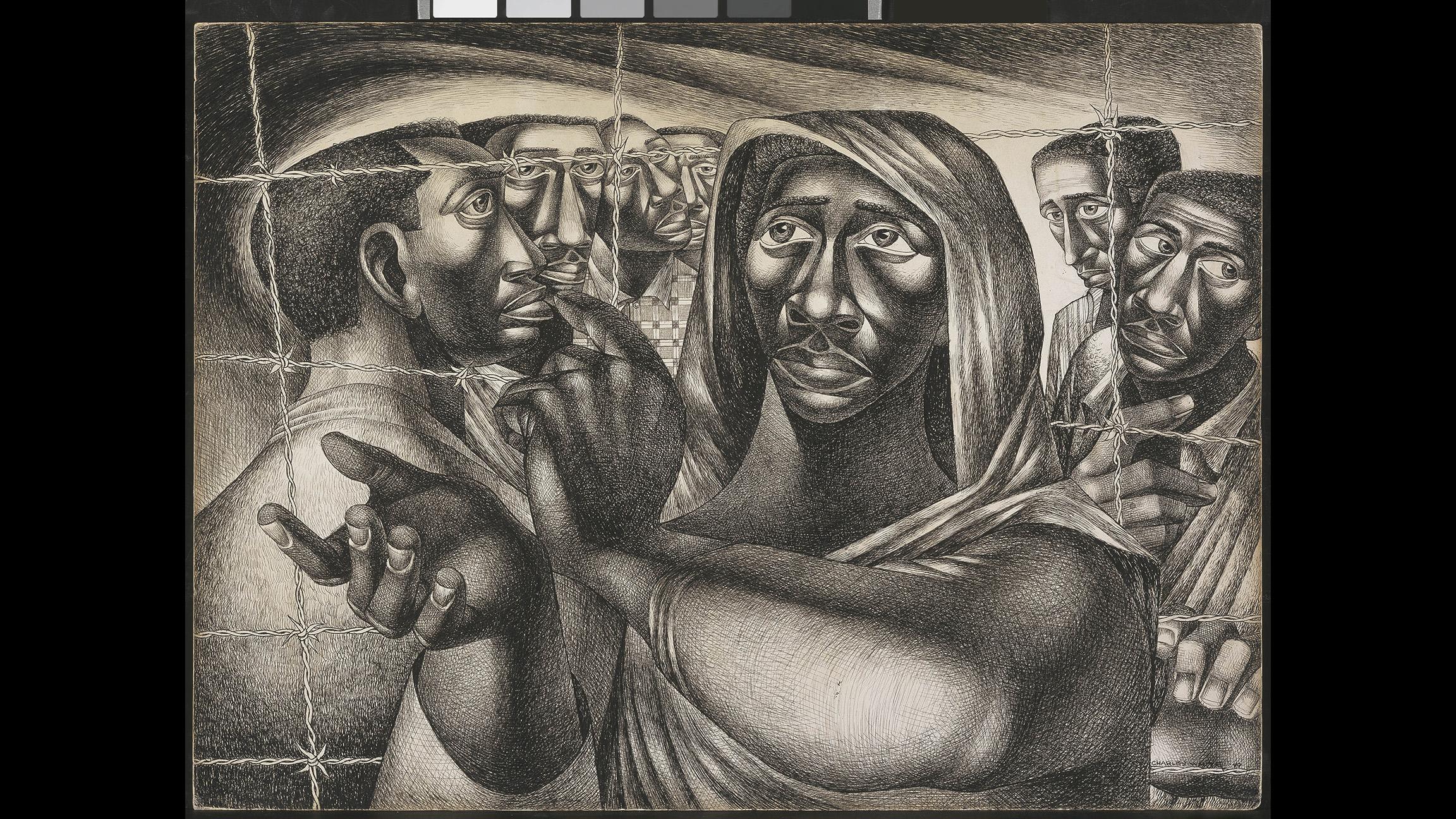

Charles White. “Trenton Six,” 1949. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

Charles White. “Trenton Six,” 1949. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

But you’ll also see anonymous sharecroppers, soldiers and laborers.

When choosing subjects for his paintings, prints and drawings, Charles White portrayed people from all walks of life.

Sarah Kelly Oehler, Art Institute of Chicago: Although he recognized the significance of historical figures such as Harriet Tubman, he also recognized that it was the everyday person who had equal merit, who could be compelling as a work of art. He really wanted to dignify the person around the corner, the woman working in the fields, the construction laborer, simply because he knew that that had meaning.

Friedman: Born in Chicago in 1918, Charles White found lifelong inspiration from regular visits to his mother’s family in Mississippi.

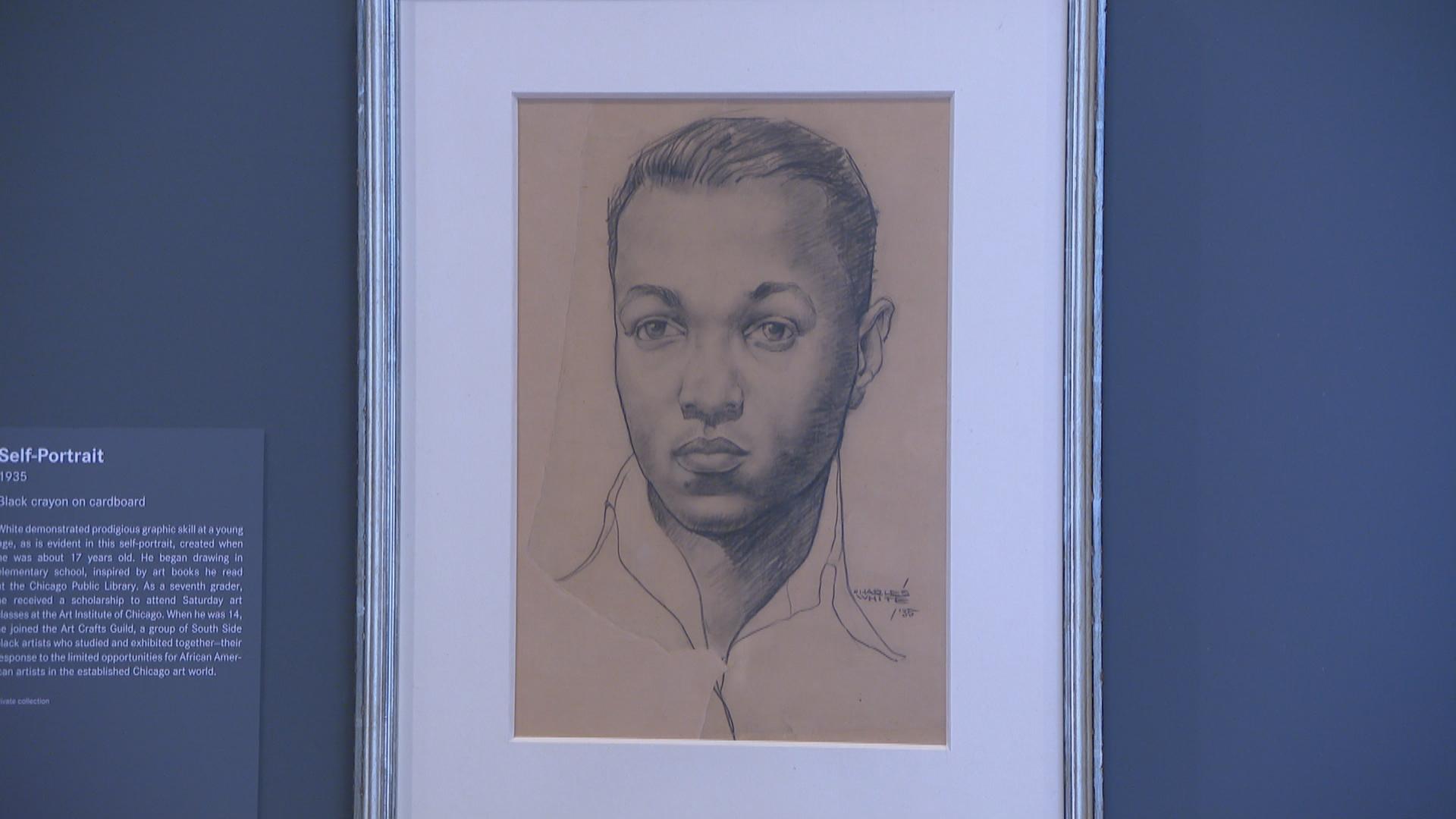

Seen here in an early self-portrait, White attended Englewood High School and was awarded a scholarship to the School of the Art Institute in 1937. He also taught at the South Side Community Arts Center and created murals for the WPA.

Oehler: He is an amazing artist and I think what’s so extraordinary about Charles White is that he always had a message.

He was a very socially conscious artist but he always wanted to pair that message with the most impeccable artistry he could, and in fact it’s not ever the same – what you see throughout this exhibition are extraordinary works, but he’s always pushing himself. He always evolved as an artist to think about new ways of presenting what he wanted to say and how to really amplify his message through just absolutely glorious artworks.

African-American history was White’s most important theme. He actually came across this knowledge very early on. As a young boy he was spending time at the Chicago Public Library reading voraciously, and he described discovering what he felt was this secret history that wasn’t being taught in his schools at the time, and so he really set himself the goal of bringing African-American history to the forefront through these big bold beautiful works.

Friedman: He collaborated with other black artists of the day – and contributed these works to the Hollywood movie “Anna Lucasta,” featuring Sammy Davis Jr. and the actress and singer Eartha Kitt.

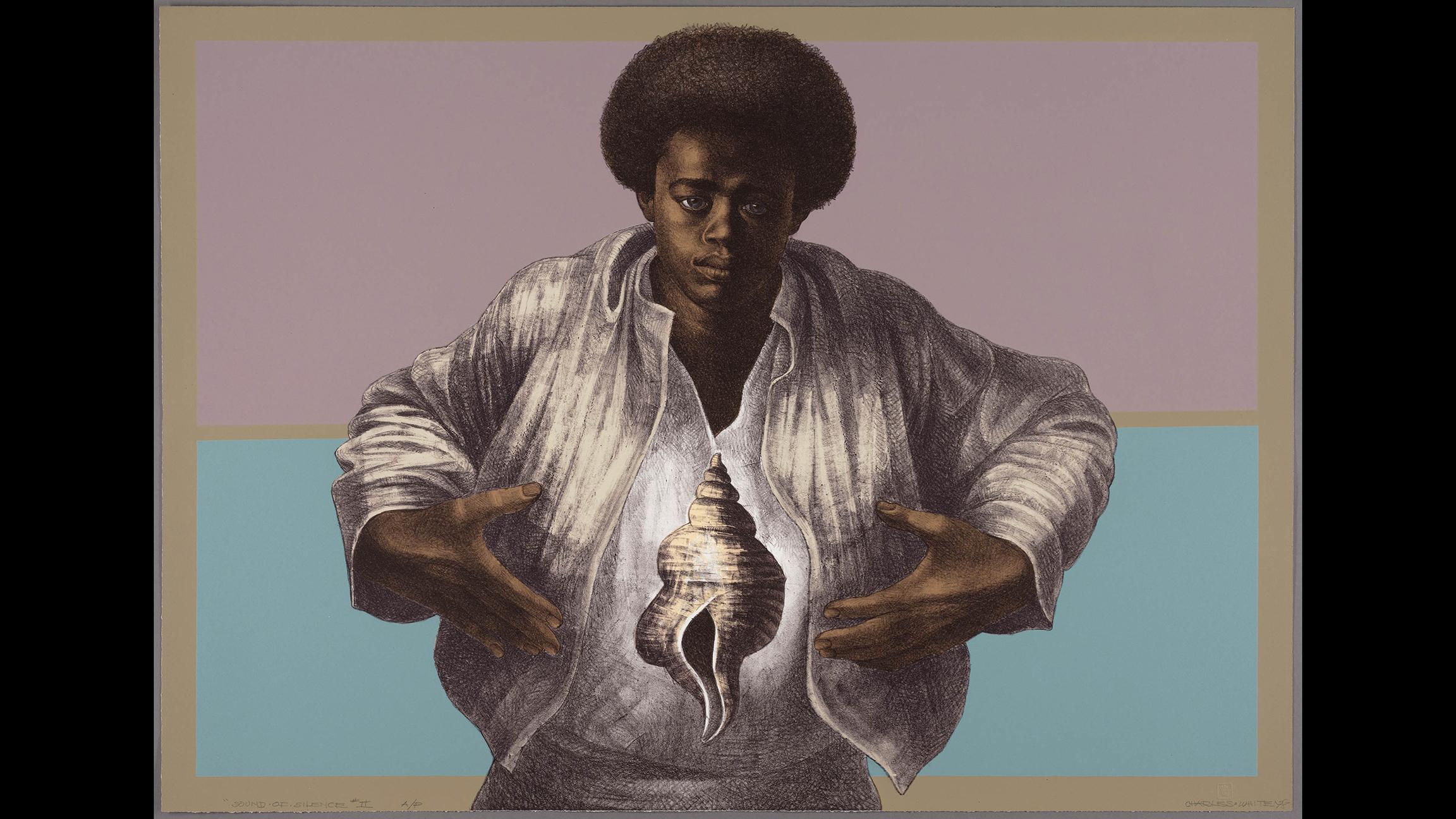

Throughout the galleries, viewers can chart the artist’s evolution. By the 1970s he was rendering realistic figures.

But earlier works show a different approach to the human form.

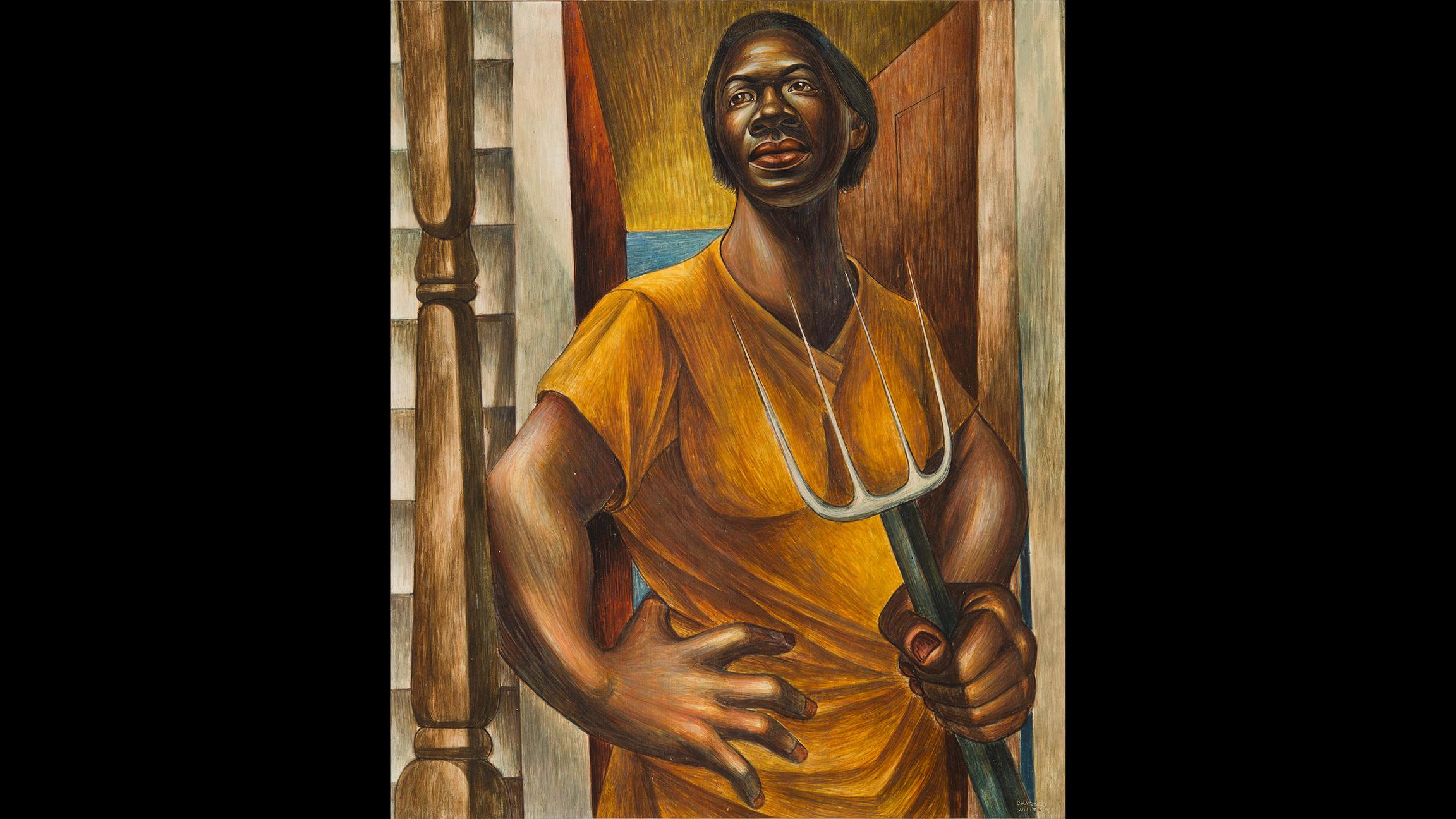

Oehler: This is a painting called “Hear This” and it dates to 1942, and White in his earlier works was using a figural style that was much more stylized, it was angular, it had some sense of distortion, and that’s because he’s very interested in several different influences and that includes Cubism, he’s looking at Cubist form. He’s looking at the Mexican modernists who likewise often used a more angular figurative style, and he’s creating these forms, these figural forms, that have this inherent sense of tension to them because of the slight distortions of form.

Friedman: After Chicago, Charles White moved to New Orleans, New York and later Los Angeles, where he taught art and mentored a generation of upcoming artists – including Kerry James Marshall, a current Chicago artist whose work has become world-renowned.

All the while, White continued to paint, draw and make prints.

Oehler: Consistently throughout this retrospective you’ll see his commitment to the figure, particularly this idea that all people had dignity and that should be celebrated through art, but this is something that in fact was quite at odds with mainstream art trends throughout much of White’s career. He was working at a time when, for example, abstraction was really a dominant mode of expression, and he felt that was cold and anti-humanist and so he wanted to express a much more humanist approach to art making.

Charles White. “Our Land,” 1951. Private Colllection. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

Charles White. “Our Land,” 1951. Private Colllection. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

Charles White is certainly one of the exceptional graduates of the School of the Art Institute.

And I think one of the things that's really significant to note about the School of the Art Institute at this time is that it was also incredibly interracial. It was very willing to accept black students at a time when many other academies wouldn’t, and White in fact always told the story of being accepted at two other academies who then rescinded their offer once they realized he was an African-American man.

Friedman: Charles White once said: “I like to think my work has a universality to it. I deal with love, hope, courage, freedom, dignity – the full gamut of the human spirit.”

Oehler: White was dedicated to public art. He felt it was important that anybody who wanted to see his art could see it, and it wasn’t just about an elite. It was about “art for the people.”

![]()

More on this story: Charles White died in 1979 at the age of 61. The exhibition “Charles White: A Retrospective” is on display at the Art Institute of Chicago through Sept. 3. Visit the museum’s website for more information.

Note: This story first aired on June 20, 2018.

Charles White, printed by David Panosh, published by Hand Graphics, Ltd. “Sound of Silence,” 1978. The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

Charles White, printed by David Panosh, published by Hand Graphics, Ltd. “Sound of Silence,” 1978. The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund. (© The Charles White Archives Inc.)

Related stories:

New Arts Club Show Explores Chicago as ‘A Home for Surrealism’

Ivan Albright, ‘Master of the Macabre,’ in the ‘Flesh’ at Art Institute