Vampire Weekend at Empty Bottle (Clayton Hauck)

Vampire Weekend at Empty Bottle (Clayton Hauck)

In his forward to the soon-to-be released “The Empty Bottle Chicago,” Mountain Goats frontman John Darnielle writes:

“You remember the people who treat you well on the road. You remember them your whole life. ... Sometimes the distance between these people seems like whole worlds, but we lucked out, because we played the Empty Bottle early on.”

The Ukrainian Village music venue first opened the night before Halloween 1993 at the corner of Cortez and Western. It was really the product of efforts from Bruce Finkelman, a Chicago native who would go on to open Thalia Hall and Longman and Eagle. During its first decade, Empty Bottle would become a magnet for underground rock, post-punk and experimental music.

Chicago independent publisher Curbside Splendor is about to put out an Empty Bottle book – both a chronicle of some of its 23-year history and a collection of testimonies from the artists and fans who love it.

We spoke with the book’s editor, writer and musician John Dugan, about the venue’s significance and what keeps ‘em coming back for more.

Chicago Tonight: Empty Bottle’s been around for 23 years now. Why this book now? How long has the idea been in the works?

John Dugan: The idea was actually hatched closer to the 20th anniversary. I was brought in by the publisher, Curbside Splendor. When they brought me the idea, I thought – it is kind of remarkable how long this place has been around. We have a lot of small venues now, but not many of them have been around 23 years. For me, it was exciting to do something about a venue that was still alive and kicking, and yet had this interesting history and which had been really influential, especially in the '90s, in terms of Chicago music culture.

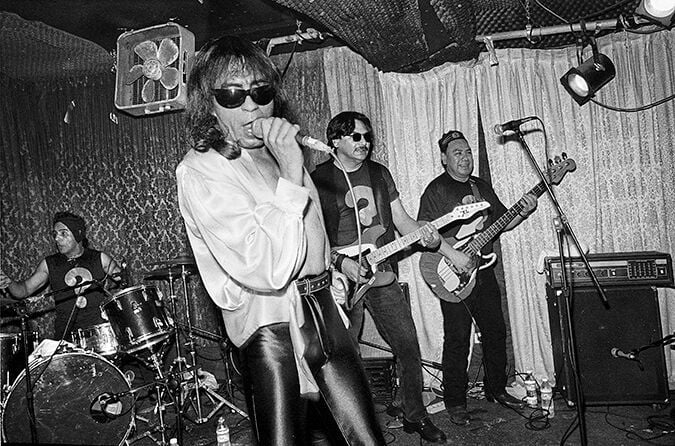

Question Mark and the Mysterians, 1997 (Marty Perez)

Question Mark and the Mysterians, 1997 (Marty Perez)

CT: You’ve got some great testimonies in the book – OK Go, the Flaming Lips, Low. Were many of those connections you had in the music industry? How did you decide who made it into the book?

JD: Initially, before I was brought on, they were looking for stories from fans. And we do have some pieces from a few literary type people who are also huge fans of underground music. But most of the folks that we interviewed or asked to write pieces were people that I knew personally or had some acquaintance with. Even some of the bigger name people we have in there – a lot of that was sort of, going through back channels.

The Winks at Empty Bottle (C Anderson)

The Winks at Empty Bottle (C Anderson)

CT: What are some moments in the book that really stand out for you?

JD: There are so many. That’s what I wanted the book to be, just sort of these little things you remember from a conversation that you want to share with somebody. One of the interviews that really blew me away was Ken Vandermark, the saxophone player who had a multi-yearlong weekly residency at the Empty Bottle. He just had such crystalline memories of playing there and how the series came about. One of the stories that was fun and interesting and showed a lot about memory, both accurate and inaccurate, was when people were talking about this legendary show where the Flaming Lips played the Empty Bottle. And some people just had it completely in the wrong month, some people thought it was at Christmas. But they all remembered this show as being this very emotional moment. One of those you had to be there things where this pretty loud band played a really quiet encore.

CT: You were also a pretty active musician in the '90s, yes?

JD: I played in a few bands in the '90s, but the one I was probably best known for was called Chisel. We played a lot of the venues in Chicago in the '90s – Fireside, the Metro, the Czar Bar. But the place we seemed to come back to the most was the Empty Bottle.

CT: You talk about the Empty Bottle being a refuge. Why do you say that?

JD: Even though we associate the '90s with alternative rock culture, a lot of the music and the different subcultures back then were pretty far outside the mainstream. They were a lot harder to access. And places like the Empty Bottle were refuges for people who didn’t necessarily want to do what they were expected to do by society or their parents or the educational system. What I remember from those days is, part of finding your own path in life could be connected to becoming a part of some sort of music culture that was kind of inaccessible to everybody else. That’s how I think of these underground rock clubs in a way. I think there’s more to them than just being places where we listen to music.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

"The Empty Bottle Chicago: 21+ Years of Music / Friendly / Dancing" comes out June 7. To pre-order a copy, visit Curbside Splendor’s website.

Empty Bottle 2009 (Clayton Hauck)

Empty Bottle 2009 (Clayton Hauck)

Below, an excerpt from “The Empty Bottle Chicago.” Flaming Lips member Steven Drozd remembers that legendary show.

Steven Drozd | The Flaming Lips

I personally went to the Empty Bottle a lot in the mid-nineties, from 1994 to ‘96. It was just the kind of drinking place I liked and all of my Chicago friends liked: cheap, friendly, with cool music.

I remember a few things. The Lips were on a real high right at that moment. We had done the second stage on Lollapalooza in 1994 and it seemed more and more people were starting to get us. Chicago had already been a second home for us, so I was really excited about that show in particular. I also remember we did a slightly different set list than usual, so it would be extra special for the hardcore fans that saw us over and over again.

We did one song where I went to the piano. It was still a novelty for me to switch from drums in those days — that crappy old upright at the Empty Bottle — and I played and Wayne sang “The Waterbug Song.” The crowd sang along quite heartily and people were just going through the roof. Like I said, it was a magical time for us. I’m pretty sure that’s how we ended the show. I think people remember us doing more songs with me at the piano, but that’s just fuzzy memory. Just that one tune and then we said, “Thank you,” and went back to drinking!

Related from "Chicago Tonight"

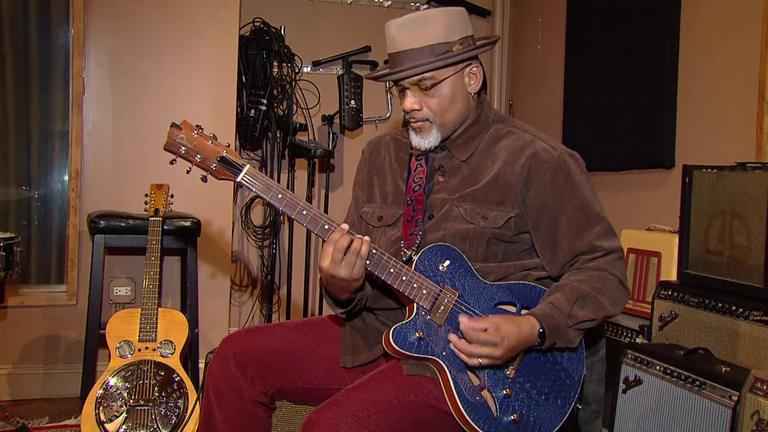

Meet the Rising Chicago Bluesman Who Drives a CTA Bus for a Living

Meet the Rising Chicago Bluesman Who Drives a CTA Bus for a Living

March 1: He is just your typical CTA bus driver, who moonlights as a sought-after Chicago blues musician. As a guitarist, singer and songwriter, Toronzo Cannon drives the sound of Chicago blues from the city to blues clubs and festivals around the world.