The state of Illinois doesn’t track the number of pharmacies that mix, combine or alter the ingredients of a drug.

The finding was reported in a new study released by Pew Charitable Trusts on Tuesday that examined state policies on compounding sterile drugs – those that are injected or infused into the body, such as IV infusions.

The practice, common at pharmacies across the country, works to “create a medication tailored to the needs of an individual patient” by a licensed pharmacist or physician, or an outsourcing facility, according to the study.

“The need for sterile preparation of a product is tantamount. Otherwise there’s a risk of an adverse event in a patient,” said Simon Pickard, the project lead for the study who is an associate professor at UIC College of Pharmacy.

“Adverse events” can include illness and in some cases death.

Read the report.

“Because most sterile drug compounding involves a drug introduced through intravenous solutions or injections, there’s the possibility of introducing contaminants directly into the body if the drug hasn’t been compounded in sterile conditions,” Pickard added. “It’s not just the drug. It could be the manner in which the drug is prepared.”

Compounded drugs, though common, are not FDA approved, and while the FDA can enforce applicable federal laws over pharmacies, states are largely responsible for regulating the production of compounded drugs.

This regulation varies from state to state, according to the study.

Of the 43 states that participated, roughly half require sterile compounding to fully conform to the widely recognized quality standards set by the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention.

While Illinois is not one of those states, the report states it “will under pending policy change.”

“Illinois is currently working to update its policies and that’s true for many states,” said Elizabeth Jungman, the director of Pew’s public health program. “A draft was released in 2014 in regards to updating the state’s quality standards and it hasn’t been finalized yet, but it’s something the state is working on.”

The Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation (which is responsible for setting and regulating those policies), was not immediately available for comment, but the May 16, 2014 Illinois Register Rule of Governmental Agencies shows the proposed amendment for pharmaceutical compounding standards (see page 274). The amendment states in part:

“All pharmaceutical compounding standards, both sterile and non-sterile, shall be governed by the USP-NF, as set forth in USP on Compounding: A Guide for the Compounding Practitioner (2013).”

“The other place [where Illinois could improve] is to begin systematically tracking compounding facilities in the state,” Jungman said. “Illinois doesn’t currently track who is compounding in-state or who out of state is shipping sterile compounds to Illinois. Tracking this could target oversight investigations to make sure compounding quality standards are being met.”

How are pharmacies inspected in Illinois?

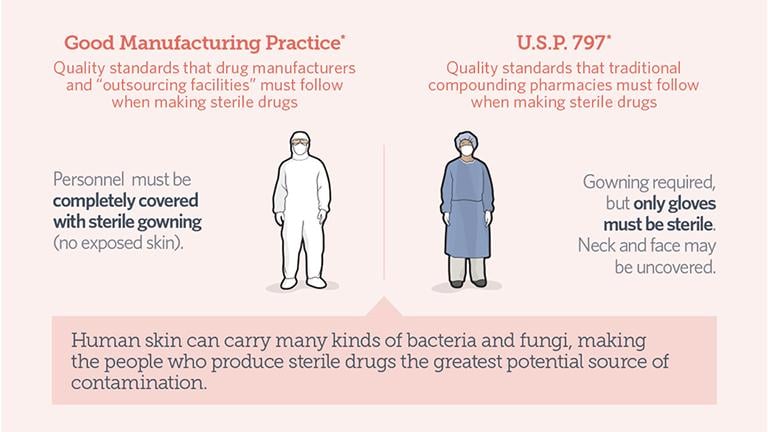

Infographic: Click to see quality standards for drug manufacturers and outsourcing facilities, left, and traditional compounding pharmacies. (Credit: Pew Charitable Trusts)

Illinois pharmacies that perform sterile compounding are not frequently inspected, according to the study. Nor do they need a separate license. Unannounced inspections do occur at the time of initial licensure, licensure renewal, when a pharmacy remodels or moves location, or when a complaint or incident occurs. Inspections typically last between four and eight hours, according to the report.

Infographic: Click to see quality standards for drug manufacturers and outsourcing facilities, left, and traditional compounding pharmacies. (Credit: Pew Charitable Trusts)

Illinois pharmacies that perform sterile compounding are not frequently inspected, according to the study. Nor do they need a separate license. Unannounced inspections do occur at the time of initial licensure, licensure renewal, when a pharmacy remodels or moves location, or when a complaint or incident occurs. Inspections typically last between four and eight hours, according to the report.

Further, direct observation of sterile compounding isn’t required when a pharmacy is being inspected. Instead, the state can take and test samples of sterile compounded drugs for inspections or investigations.

Less than a quarter of the states that participated in the study reported direct observation of sterile compounding, according to Jungman.

“The idea is when an inspector goes in to inspect a pharmacy they are looking at sterile compounding activities even if it’s simulated, if they’re not doing it that day,” Jungman said. “They would walk through a simulated compounding operation so inspectors can ensure that proper quality procedures are being followed and only 23 percent of responding states required that. That’s a real opportunity for a lot of states.”

What happens if something goes wrong?

Of the 43 states that participated in the study, only four require that pharmacies report adverse events to the state and MedWatch, the FDA safety information and adverse reporting program. Eleven states require a report to the state, and four states require a report only to MedWatch, according to the report.

Illinois is not among them.

“There have been tragic failures,” Jungman said.

From 2001-2015, Pew’s drug safety program identified more than 25 compounding errors or potential errors associated with 1,076 adverse events, including 90 deaths.

In 2012-2013, 751 people were infected and 64 people died during a nationwide outbreak of fungal meningitis that was linked to contaminated injections made by a compounding pharmacy. Illinois was one of the 20 states impacted by that outbreak.

In 2010, an Illinois infant died from a fatal overdose of an IV solution (sodium chloride) that was 60 times stronger than the dosage ordered.

“When dozens died and hundreds were injured from contaminated injections in 2012-2013, quality standards had not kept pace with changes in compounding and that presents a patient safety risk that could affect you,” Jungman said.

What are the best practices?

Released in conjunction with Pew’s study was a report that outlines the best practices for state oversight of drug compounding.

Read the report.

“This is a transitional time for states, and states are already looking at policy changes,” Jungman said. “We hope the best practices study can be used as a resource for states reevaluating this and help give them structure and guidance on policy changes they’re making.”

Illinois could implement “regular inspections, especially if you have finite resources, stratified by resource, what might be considered higher-risk facilities should take priority,” Pickard said. “Have a mechanism to track physician office compounding, [work with] other states to track compounding over state borders, and create a separate licensure for sterile compounding."

While Pickard hopes these best practices will be adopted by states, including Illinois, he understands there are limitations.

“My main hope but also my concern is that when you recommend greater oversight of something, that requires enforcement and enforcement requires resources, and we know very well that a lot of states have limited resources at this point in time,” he said. “As you know for the state of Illinois, we’re in a budget crisis right now and my concern is in the grand scheme of things where does this fall as a priority for the state legislators.

“The funding doesn’t seem to be coming from the federal government and there are so many competing priorities in the state. I wonder the extent to which this will resonate with policymakers. If we don’t do something about it, it’s just a matter of time before we see more unfortunate consequences of a lack of oversight of this area.”

Follow Kristen Thometz on Twitter: @kristenthometz