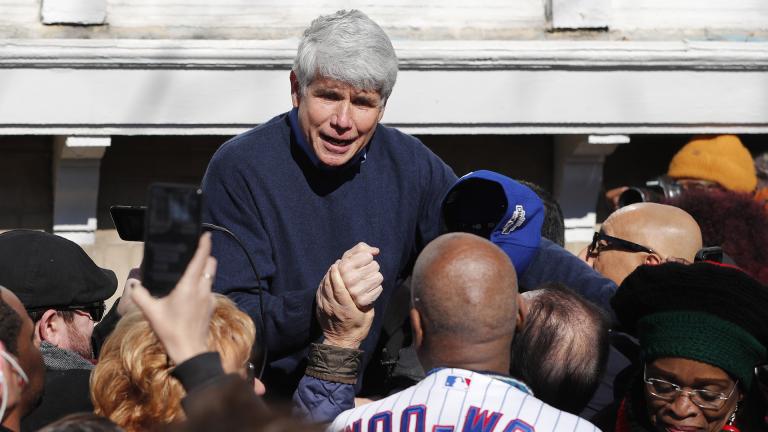

We talk with the Chicago Tribune reporters who've written a book digging deep into Rod Blagojevich's past on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm.

Read an excerpt from Golden: How Rod Blagojevich Talked Himself Out of the Governor's Office and Into Prison by Jeff Coen and John Chase:

On October 28, investigators scored another hit. This time, Robert [Blagojevich] was taped in the conference room on the phone with his brother. The 2008 presidential campaign was drawing to a close, and signs were pointing to Obama emerging as the winner. To say the least, this was expected to have an enormous effect on Illinois and Chicago, and Blagojevich would be expected to appoint someone to replace Obama when he gave up his seat in the US Senate and headed for the White House to become the country’s forty-fourth commander in chief. Investigators weren’t even exactly sure what they were hearing when they captured the half of the conversation they could hear from Robert.

“Now here’s the big issue he came up with, and I don’t know if you want to listen to this or not,” Robert was heard to say.

“But it has do to with a particular person who is lobbying to be the senator, um, and wants to talk to you about his resume, Jackson,” Robert said, talking about Jesse Jackson Jr. “And Raghu Nayak evidently supported it, and he had communicated through Rajinder that if in fact, um, that would be the case, ah, there would be some accelerated fund-raising on your behalf between now and the end of the year, through his network. And I said look, and, uh, they haven’t even, and I, I completely told him, you know, we don’t even know who the president is gonna be yet.”

The men Robert was talking about were Raghu Nayak and Rajinder Bedi, two players in Chicago’s Indian community who had become major Blagojevich supporters.

Nayak was a businessman from west suburban Oak Brook who owned surgery centers all over Chicagoland. He had been friends with Blagojevich and Jackson for years, donating more than $200,000 to the governor and $22,000 for Jackson. Bedi was a Blagojevich fund-raiser and had received a state job after Blagojevich became governor.

Prosecutors were constantly adding new information to their requests to expand the recording operation. And the day after Robert’s call, October 29, the judge approved the broadening of the taping to permit the interception of telephone calls to Robert’s cell phone, to the governor’s Chicago home where he was conducting most of the state’s business, and to the campaign offices. He would occasionally conduct meetings at the James R. Thompson Center, the state’s main government building in Chicago, but liked to avoid it if he could. An appearance in Springfield was an even rarer occurrence, as Blagojevich stayed away from the capital as much as possible.

The wiretaps were activated that same day by 6:00 pm, with calls to both numbers being routed into the FBI’s satellite office in Lisle, a suburb west of Chicago. It was from there that Supervisory Agent Pat Murphy and Agent Daniel Cain and others had been running Operation Board Games. All of the files were there, so it made sense to have Lisle be the center of the listening effort. The FBI suddenly found itself monitoring a total of nine phone lines, needing two agents available for each from early in the morning until around eleven o’clock at night. It didn’t take long to run through one hundred agents a week, and Cullen found himself shifting agents from squads handling health-care fraud and bank fraud to cover listening shifts. Agents from all over the bureau in Chicago were volunteering because of the high-profile nature of what was happening and because of how profitable to the investigation the calls quickly became.

The idea that Blagojevich could be illegally attempting to get something for himself for the Senate seat was still a new concept. Some agents on the case were listening only for calls about fund-raising irregularities. The rules on wiretapping require agents monitoring phone lines to stop recording, or “minimize” the calls, when something personal or unrelated to the investigation comes up. So as the taping began, prosecutors who were getting discs of the calls were finding that the new agents to the case were minimizing when Senate discussions began. The assistant US attorneys quickly rectified the situation. They told the agents to let the recordings continue when a replacement for Obama came up.

The Rod Blagojevich who would be captured on hundreds of federal recordings was becoming a desperate man, a politician at a crossroads who was seeing the best years of his career ending and only questions ahead. His original presidential aspirations had never developed, and worse yet, another dynamic politician from Illinois was riding the wave to the office that Blagojevich himself had hoped to catch. And Obama was taking some of the state’s best and brightest with him for his cabinet, adding to Blagojevich’s sense that he was being left behind. Obama was headed for Washington and the history books Blagojevich loved so much, while he seemed destined to be a historical footnote.

Blagojevich was also simply tired of being governor. He felt underappreciated, as polls showed just a fraction of the state’s voting public liked what he was doing. He had taken to political gimmicks, like giving seniors free passes to public transportation, to try to recover his image. Meanwhile, he was feeling the pressure of the federal investigation, reading regularly about

Rezko’s possible cooperation. His own legal bills were mounting, as he was paying some of the city’s top lawyers to handle federal requests for documents. It was a tab he could pay from his campaign fund, but he was facing problems there, too. His coffers were dwindling, and his ability to refill them was about to be seriously curtailed. With the new ethics bill going into effect at the end of the 2008, firms doing business with the state would no longer be allowed to make large campaign donations.

By the fall of 2008, Blagojevich was separated from his lawyers at Winston & Strawn, as he had become embroiled in a dispute over their pay. Also factoring in the split from Winston’s perspective were complaints from federal prosecutors that the same law firm should not be representing Blagojevich and Cellini, who remained under investigation and was represented by one of its top lawyers, Dan Webb. Blagojevich was left with Sorosky, who had previously remained on the sidelines for the governor and now found himself front and center. “I may just be a finger in the dike, but I’m his lawyer,” he told federal prosecutors.

Blagojevich had appeared at a second meeting with the FBI while being represented by Winston & Strawn, not long before his reelection in 2006. But when investigators asked to see him again in late October 2008, Sorosky told them Blagojevich would invoke his Fifth Amendment rights. The attorney didn’t know it then, but the request was an apparent attempt to lock Blagojevich into statements that would contradict what agents were hearing on their recordings.

With the investigation all around him, Blagojevich was unlikely to be in the state’s political mix beyond 2010. And longtime nemesis House Speaker Michael Madigan had called for a committee to begin studying impeachment. The newspaper editorial boards were also starting to think it was a good idea, casting Blagojevich in an increasingly negative light. An end to his political career would leave him with almost no options to continue giving his family the kind of life they had enjoyed. Money was going to be a problem after he left office, and Blagojevich didn’t have the kind of reputation that sometimes led to high-paying jobs for ex-politicians. He was damaged goods. No law firm would pay to put his name on the door, using him as a trophy. No major corporation would want him as its figurehead. And no one was going to pay to see him on the lecture circuit. In short, he needed an escape hatch.

And he would find one, at just the wrong time. The recipe crystallized just as the feds flipped the switch on their recordings. In Blagojevich’s delusional mind, the one good thing about Obama’s election was that it left him with the ability to choose the president-elect’s replacement in the Senate, and he was determined to try to maximize it for his own benefit. It was a final trump card that he could play to end many of his problems at once. Get him money and a job prospect after he left office. End the threat of impeachment. He could even pull the rip cord on a golden parachute and name himself. Get him out of Illinois. Get him to Washington.

The final ingredient in the explosive cocktail came from the incoming president. As was his prerogative, Obama also had thoughts about who might replace him. He wanted someone he knew and could work with, and someone who could hold the seat for the Democrats and maintain the balance of power in Washington that he was enjoying at the beginning of his first term. So Obama had reached out through intermediaries to communicate his wishes at the same time Blagojevich was turning things over in his mind and imagining what his best strategy would be. With Obama invested in the pick, Blagojevich thought he had all but won the lottery. All of his enemies—Madigan, the newspapers, and even the feds—Blagojevich dreamed, were about to see that he could still outsmart them all.