The rules that govern when — and how — Chicago police officers can use force against members of the public are complicated and subject to interpretation, despite years of efforts to make it less likely that an altercation between an officer and a Chicagoan turns deadly.

Those rules, crafted by officials after decades of Chicago Police Department scandals alleging misconduct and brutality, now face new scrutiny after officers shot and killed Dexter Reed on March 21. Preliminary evidence “appears to confirm” that Reed fired first, wounding an officer, before four officers responded by firing 96 shots in a matter of 41 seconds, according to the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, the agency known as COPA that is charged with investigating police misconduct.

Here’s a breakdown of when Chicago police officers can use force and how those rules will shape the investigation into Reed’s death.

What do we know so far about what happened to Dexter Reed?

Reed, 26, was driving a GMC SUV about 6 p.m. March 21 when he was stopped by a tactical team of five officers, who were not in uniform, near the border of Humboldt Park and Garfield Park.

Multiple officers surrounded his vehicle while ordering him to roll down his window, but Reed did not comply, and officers pointed their guns at Reed. Video from the surrounding area and officers’ body-worn cameras “appears to confirm” that Reed fired first, striking an officer in the forearm, who was seriously wounded but is recovering, according to COPA. Four officers fired approximately 96 times during a period of 41 seconds toward Reed, including after he got out of his car and fell to the ground. It is unclear how many times, precisely, Reed was shot.

Let’s back up. Do we know why Reed was stopped in the first place?

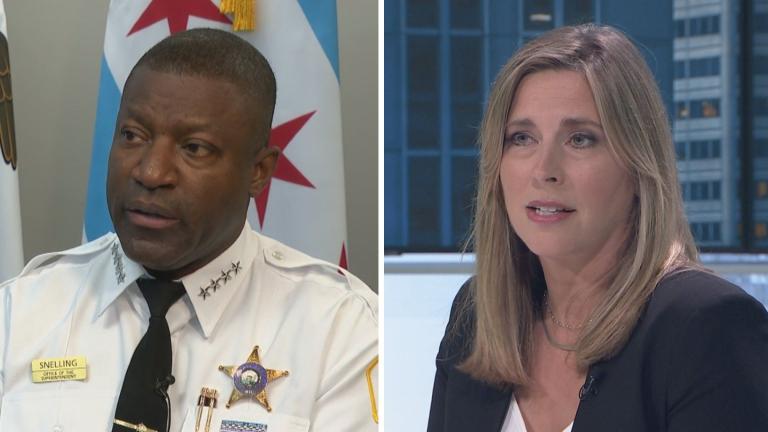

Reed was stopped “for purportedly not wearing a seatbelt,” according to COPA. But Andrea Kersten, the agency’s chief administrator, told Supt. Larry Snelling that her agency isn’t sure how officers could have seen Reed wasn’t wearing his seat belt, since the windows of the SUV Reed had just purchased were tinted. COPA has “serious concerns about the validity of the traffic stop that led to the officers’ encounter with (Reed),” Kersten wrote in a letter to Snelling.

Can Chicago police officers stop you if they think you’re not wearing a seat belt?

Yes. Nearly 73% of the 537,000 traffic stops in Chicago in 2023 were prompted by improper registration or an equipment violation, like failing to wear a seat belt, according to a report released Thursday from Impact for Equity, a nonprofit advocacy and research organization that has helped lead the push to reform the Chicago Police Department.

The group has called for those kinds of stops, which they say are designed to find evidence of other crimes or “pretextual,” to be banned.

More than half of all drivers stopped by police in Chicago in 2023 were Black, like Reed, according to that report.

Why did officers point their guns at Reed during a traffic stop initiated by a seat belt violation?

That’s one of the big questions that investigators will be trying to answer, since CPD rules consider an officer’s decision to point a gun at a member of the public to be a use of force that must be reported and reviewed by their superior officers and those charged with overseeing the CPD.

Two probes are ongoing: one by COPA, which could lead to the officers being disciplined or fired, and one by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, which could lead to criminal charges.

So COPA and Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx will determine whether officers were justified when they shot Reed?

Yes, but while the two probes will examine the same evidence, they will try to answer different questions.

COPA’s job is to figure out whether officers followed CPD’s De-escalation, Response to Resistance, and Use of Force policy.

Foxx will ultimately determine whether she thinks the officers committed a crime, and whether prosecutors have enough evidence to bring to a jury.

Video: Joining “Chicago Tonight: Black Voices” to discuss the ongoing investigations into Dexter Reed’s death are Arthur Lurigio, a professor of criminal justice and psychology at Loyola University Chicago; and Sharon Fairley, a University of Chicago Law School professor who previously served as chief administrator of the Independent Police Review Authority, or IPRA, the agency then responsible for police misconduct investigations. (Produced by Emily Soto)

Let’s take the investigations one by one. What does CPD’s policy say?

That policy, last revised in 2023, sets the department’s highest priority as the sanctity of human life. It also requires officers to use de-escalation techniques and only respond with increasing levels of force when “objectively reasonable, necessary and proportional based on the totality of circumstances that the officer was confronted with,” Kersten said.

Using lethal force, like firing a gun, must be a last resort, in direct response to an imminent threat to the officer, another officer or someone else, according to the policy.

CPD’s policy is more restrictive than state or federal law, which could lead to an officer being disciplined for actions that do not lead to criminal charges.

A final decision won’t come until after investigators determine whether there is a preponderance of evidence, a lower burden of proof than in criminal cases, that officers violated the policy.

Why was the policy rewritten in 2023?

The court order known as the consent decree, which requires CPD to change the way it trains, supervises and disciplines officers, prompted the changes to the policy. Other changes to the policy were prompted by CPD’s handling of the protests and unrest triggered by the police murder of George Floyd, which Chicago’s watchdog said the department botched from top to bottom.

What about the criminal investigation?

It is very rare for officers to be charged with criminal wrongdoing in an on-duty shooting, in part because officers are permitted under federal law to use deadly force in some cases.

But Foxx’s office will determine whether the use of force in this case was warranted. If her office determines the shooting was not justified, then Foxx and her deputies will decide whether they can prove the officers committed one or more crimes beyond a reasonable doubt.

That will not be a quick, or easy, process, Foxx said.

How long will it take?

It will likely take months for the two investigations to be completed, ensuring that this issue stays in the spotlight.

Are the officers still on active duty?

No. All five officers who were involved in this shooting will be limited to administrative duties at least until April 21, 30 days after the incident.

COPA has urged Snelling to strip all of the officers of their police powers while the investigation is pending because the agency has “grave concerns about the officers’ ability to assess what is a necessary, reasonable, and proportional use of deadly force.”

Snelling has yet to respond to that recommendation.

Does it matter if the probes conclude that Reed shot first?

Yes. CPD’s policy allows officers to meet deadly force with deadly force, and a gun was recovered from the front seat of Reed’s car. But that does not mean that the other parts of the policy don’t matter — including the requirement that officers respond proportionally. The probe will no doubt focus on the fact that Reed died after getting out of his car, and appears to have been shot while on the ground.

Remember, CPD’s policy allows officers to use force only in the face of an imminent threat. Investigators now have to determine whether Reed, who was struck multiple times, posed a threat after collapsing.

What about the fact that officers fired at Reed 96 times?

That will also be a key consideration for investigators, who will also be tasked with determining whether officers reloaded their weapons in order to continue firing at Reed and whether Reed posed a deadly, imminent threat at that point.

Is CPD in compliance with all elements of the consent decree, which aims to prevent unjustified use of force?

CPD has fully met just 6% of the court order’s requirements, according to the most recent report by the team monitoring the city’s compliance with the consent decree released in November. That, like these probes, is very much a work in progress.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]

A Safer City is supported, in part, by the Sue Ling Gin Foundation Initiative for Reducing Violence in Chicago.