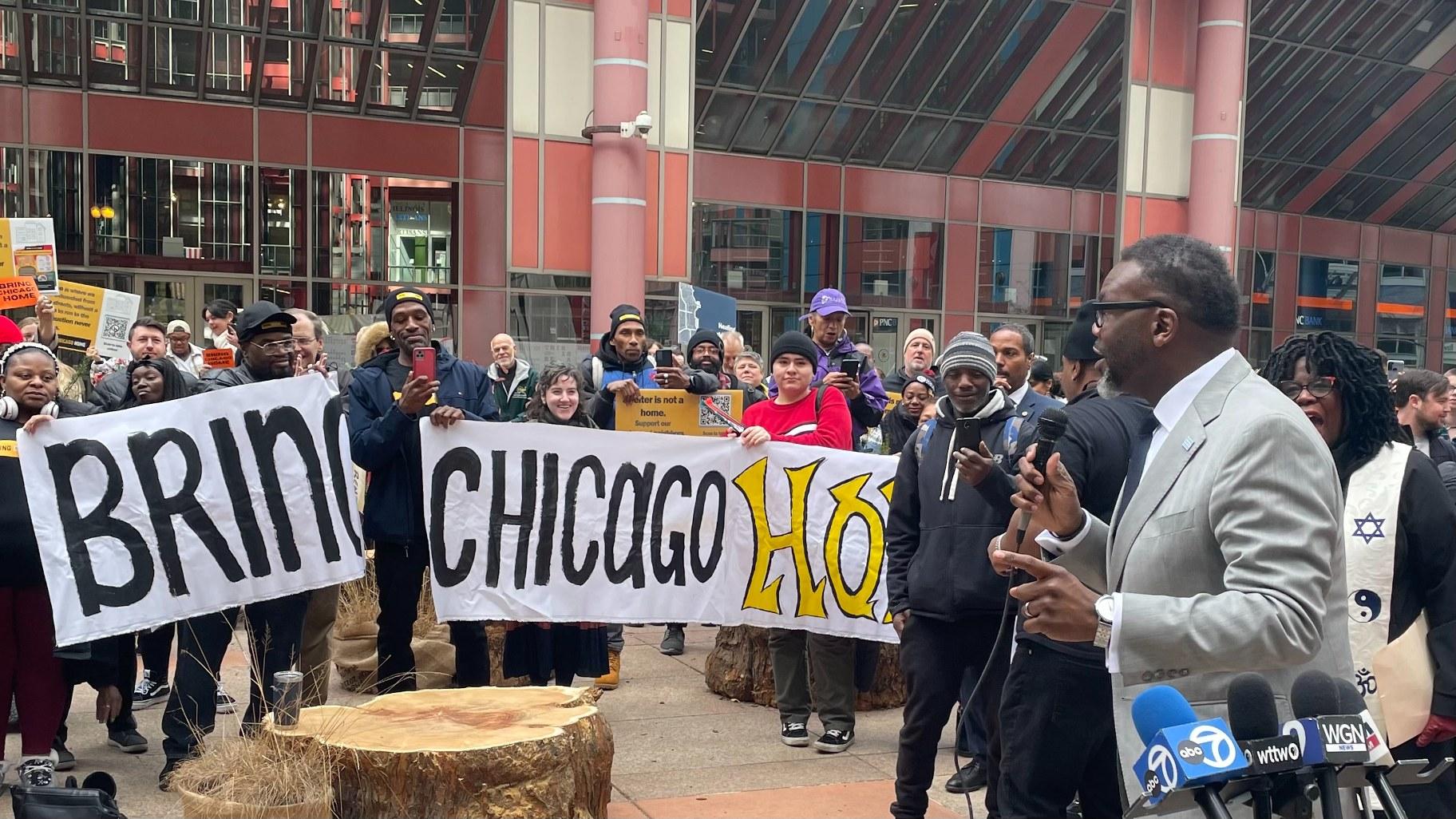

Mayor Brandon Johnson rallies supporters of the proposal known as Bring Chicago Home on Tuesday, Nov. 7, 2023. (Heather Cherone / WTTW News)

Mayor Brandon Johnson rallies supporters of the proposal known as Bring Chicago Home on Tuesday, Nov. 7, 2023. (Heather Cherone / WTTW News)

Chicago voters will get to decide during Tuesday’s primary whether to give the Chicago City Council the power to hike taxes on the sales of properties worth $1 million or more to fight homelessness, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled Wednesday.

With three of the seven justices abstaining, the state’s highest court rejected an appeal from a coalition of real estate and development groups that sued the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners to knock the ballot measure off Tuesday’s ballot.

Justice Joy Cunningham, who is up for reelection on Tuesday, Justice Mary K. O’Brien and Justice P. Scott Neville took no part in the decision. They gave no reason why, in keeping with the rules governing the state Supreme Court.

That decision upholds a unanimous March 6 ruling by a 1st District Appellate Court panel that had overturned a Feb. 23 decision by Cook County District Court Judge Kathleen Burke invalidating the binding ballot question known as Bring Chicago Home and ordered the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners not to count votes cast by Chicagoans.

“Voters now have the power to set Chicago on a new path: where big corporate landlords pay their fair share, where there is legally dedicated local funding for affordable housing and support services, and where 68,000 homeless Chicagoans have a place to call home,” said Doug Schenkelberg, executive director of the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, which helped craft the proposal.

The Building Owners and Managers Association of Chicago and other opponents sued to knock the proposal off the ballot while vigorously campaigning against the plan to hike the city’s Real Estate Transfer Tax, warning that it could cause the city’s already-struggling commercial real estate market to collapse amid the shift to remote work.

“The court’s inaction doesn’t say anything about the issue itself, which is a complicated and misleading plan for a tax increase— which will impede the creation and preservation of naturally occurring affordable housing,” Neighborhood Building Owners Alliance President Michael Glasser said.

The Supreme Court’s decision came on the same day that the Civic Federation, a nonpartisan fiscal watchdog, determined that the proposal is not detailed enough to determine whether it will adequately address Chicago’s homelessness problem.

At the same time, the Civic Federation, led by former Inspector General Joseph Ferguson, said the proposal “could further compromise the economic health of an already troubled downtown commercial sector in Chicago, posing additional risk to the City’s economic future.”

A statement from the office of Mayor Brandon Johnson thanked the Civic Federation for its feedback but said the office disagreed with the findings.

“Over 68,000 Chicagoans are currently experiencing homelessness, and the city needs flexible, dedicated revenue to create long-term, structural solutions to address this challenge,” the statement said. “There is little concrete evidence at this point that this one-time marginal tax at point-of-sale would have a major negative impact on the industry.”

The Chicago City Council voted 32-17 in November to put the measure to voters. If it is approved, it will be up to the City Council to decide whether to implement its new authority.

The last time Chicago voters passed a binding referendum that applied to the entire city was 1885, when they voted to create the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners, according to city records.

Johnson and other supporters of the proposal said city officials have a moral obligation to house as many vulnerable Chicagoans as possible to confront the growing number of unhoused residents while ensuring wealthy residents of Chicago pay their fair share.

The proposal would slash the real estate transfer tax paid by Chicagoans who sell residential and commercial properties for less than $1 million by 20%, while hiking taxes on transactions of more than $1 million by as much as 400%.

That would generate approximately $100 million annually, which supporters say would be enough to address the root causes of homelessness by building new permanent housing that offers wraparound services like substance abuse counseling in an effort to combat crime and poverty throughout Chicago.

An August report from the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless found that the number of Chicagoans who do not have a permanent home grew 4% between 2020 and 2021, to 68,440 people.

State law does not give the City Council the power to change the transfer tax on its own authority. Without legislation passed by the General Assembly and signed by the governor, the measure needs the support of Chicago voters through a referendum before the City Council can levy the tax and collect the funds.

Under the current law, the buyer of a home worth $300,000 pays the same flat transfer tax as the buyer of a multimillion-dollar mansion or downtown skyscraper — a fact that supporters of the change contend is unfair and contributes to income inequality in Chicago.

The seller of a home sold for $500,000 now pays $3,750 in real estate transfer taxes, a 0.75% tax rate. If voters were to pass the binding referendum on the primary ballot, and the City Council were to agree to levy the tax, that cost would drop to $3,000, or a 0.60% tax rate, officials said.

Nearly 94% of all properties sold in Chicago have a final purchase price of less than $1 million, officials said.

The transfer tax on properties sold for more than $1 million would spike by 233%, but apply to just the amount of the sale greater than $1 million, in an effort to ensure the measure withstands a legal challenge and reduces the incentive for sellers to artificially lower sale prices, according to the proposal.

For example, the seller of a property that sells for $1.2 million now pays $9,000 in transfer taxes. Under the revised proposal, that would rise to $10,000, with the higher tax rate of 2% applied to just $200,000 of the sale price, according to the proposal.

Using the same mechanism, the transfer tax on properties sold for more than $1.5 million would spike by 400% with the increase only applying to the amount of the sale greater than $1.5 million, according to the proposal.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]