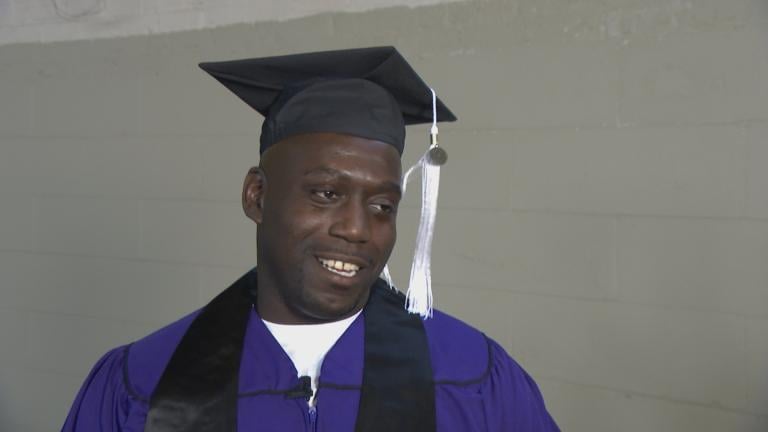

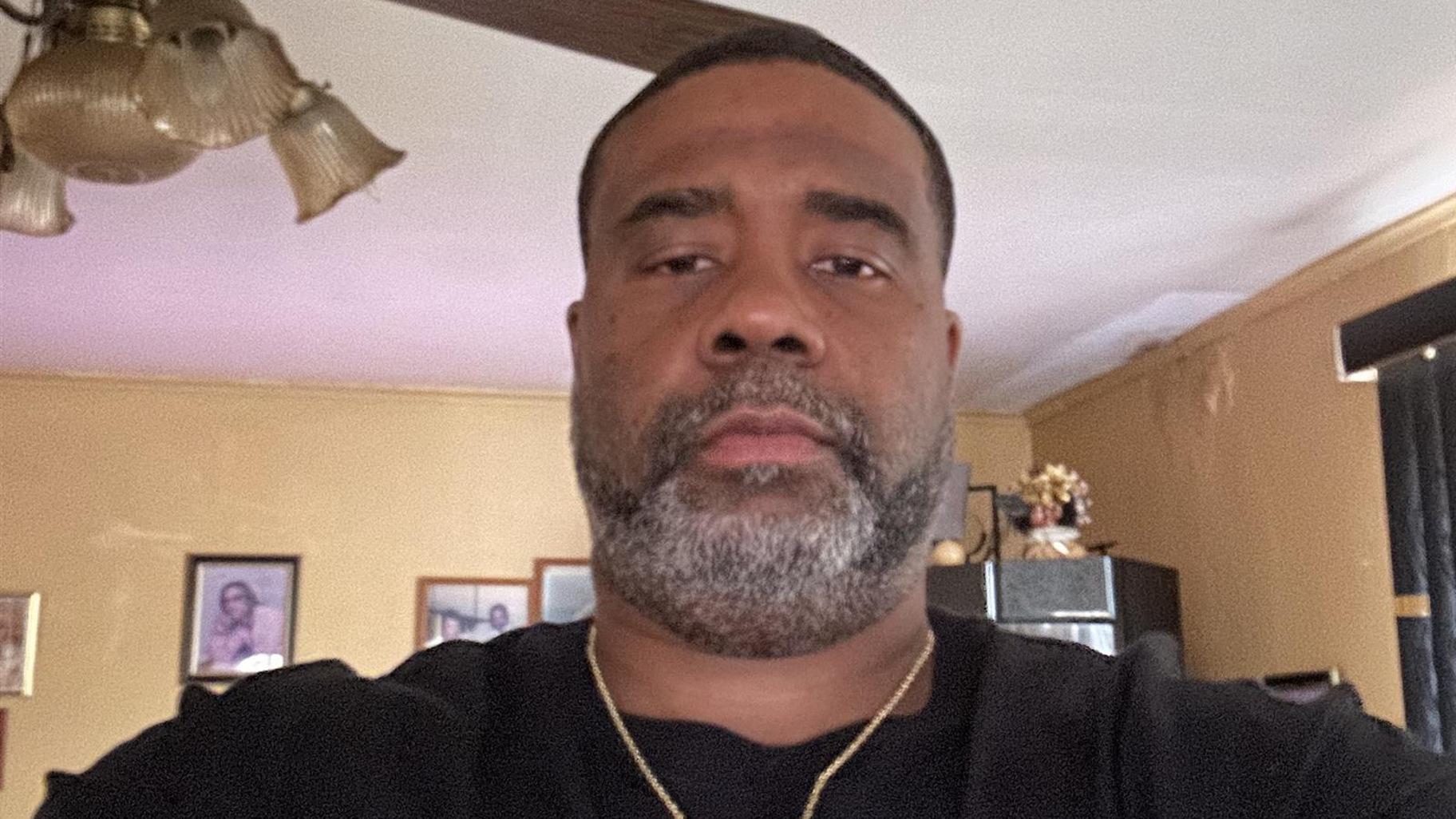

In a selfie shared with Capitol News Illinois, Charles Collins prepares for his first Christmas at home in 14 years. (Photo submitted)

In a selfie shared with Capitol News Illinois, Charles Collins prepares for his first Christmas at home in 14 years. (Photo submitted)

For at least two hours of the ride home, Charles Collins feared someone was following his father’s car, looking to take him back to prison for the rest of his life.

At an interstate rest stop between Western Illinois Correctional Center and Chicago, Collins said the reality of his freedom settled in and he let go of the anxiety. He would be with his family for Christmas for the first time in 14 years.

“It’s going to be a party, that’s for sure,” he said during an interview on Monday.

Collins, 49, was sentenced to life in prison without parole in relation to a 2010 charge for cocaine possession with intent to sell. It was his third felony, making him eligible for an enhanced sentence under the state’s habitual criminal, or “three-strikes,” law. He had two prior felonies on drug trafficking charges from 1998 to 2007 that made him eligible for the enhanced sentence. The judge told him she had no choice, he recalled, before she sentenced him to life without the possibility of parole.

“For a minute, it didn’t sink in. I was shocked that the judge went through with it,” Collins said.

The three-strikes law allows that if a defendant is convicted more than three times of the same or similar offenses, the judge can aggravate the crime to one that is eligible for a life sentence. The law was designed to combat recidivism, but advocates argue it was draconian and unfairly targeted minority defendants.

Jennifer Soble, the executive director for the Illinois Prison Project, an advocacy group for incarcerated people, noted in 2020 that 75 percent of people serving life sentences in Illinois were African American and 94 percent of people serving life sentences in Illinois for a third strike for armed robbery or drugs were African American or Latino.

Collins was the last man serving life in the Illinois Department of Corrections under the three-strikes law for drug offenses, Illinois Prison Project legal director Candice Chambliss said.

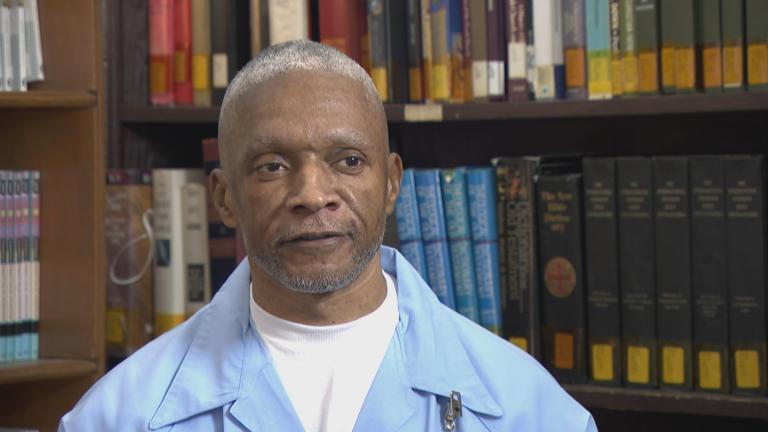

Earlier this year, Gov. J.B. Pritzker commuted the life sentence for the three people who were doing life without parole for drugs under the three-strikes law. One of those offenders, Michael Lightfoot, 67, received clemency and was released from Danville Correctional Center last month.

Pritzker commuted Collins’ sentence in February 2023 from life without the possibility of parole to parole eligible. In a rare move, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board voted unanimously last week for Collins’ release.

The Illinois Prison Project took up the cause of three-strikers in 2020, providing legal representation for incarcerated individuals. It currently has 74 pending cases for inmates serving three-strikes sentences for non-drug offenses. To date, 27 people have been released through commutation, parole, or medical release, according to Chambliss. Thirty-three others have been denied, and six people died before the governor issued a decision.

The scope of the three-strikes law has been narrowed over the years – including as part of the criminal justice reform known as the Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today, or SAFE-T Act – but the statute remains on the books in Illinois. While one lawmaker proposed a measure in the spring session that would have fully repealed it, the legislation failed to gain support in the General Assembly and did not receive a vote in committee.

“Gov. Pritzker is a lifelong advocate for criminal justice reform and signed legislation making our criminal justice system more equitable,” Pritzker Spokesperson Jordan Abudayyeh said in a statement. “The SAFE-T Act reformed the habitual offender law to ensure it is used only in the most serious circumstances.”

After his 2010 arrest, Collins spent months in Cook County Jail before he was transferred to IDOC, eventually ending up at Menard Correctional Center in Chester. He said fellow inmates who had been convicted of violent offenses could not believe he was sentenced to life without parole. For years, Collins spent time in the law library in the prison to try to find a way to have his sentence reconsidered.

“I knew it was time for me to get to work; that it couldn’t end this way for me,” Collins said.

Mira de Jong, an attorney with the Illinois Prison Project, took his case in 2020.

In an interview with Capitol News Illinois, de Jong noted that none of the crimes used to aggravate Collins’ sentence were violent but were drug offenses normally punishable by a maximum of 15 years.

“Most times, the sentence does not take into account growth and change. The system isn’t designed to help people,” de Jong said. “I don’t think there’s a lot of space for redemption there.”

After his commutation, Collins was transferred to Western Correctional Center in Mount Sterling. It was there that Collins had access to educational and reintegration programs, he said. He took advantage of the opportunities – achievements noted by the parole board.

After the holidays, Collins said he’s going to try to get his commercial driver’s license reinstated. A friend offered him a job driving a truck and later financing to start his own trucking business.

He knows he has missed a lot, time with his children and grandmother, celebrating graduations, birthdays, and holidays, grieving deaths. Through it all, Collins said his family was his constant.

Charles Dunn, Collins’ father and best friend, was at the Prisoner Review Board hearing in Springfield last week. He made the call to Collins to let him know the board’s decision.

Collins was in the barber shop at Western Illinois Correctional Center when he received that call from Dunn, who was standing outside the hearing room.

“You made it!” Dunn told Collins. “You are coming home!”

Within 24 hours, he was on the road, headed home, looking over his shoulder for the first half of the trip. He didn’t want to eat, he said. He just wanted to get home to Chicago. The only stop on the way was that rest stop where he realized no one was behind them.

“I think I have done all the right things. I have taken responsibility for my actions. I have shown remorse for those poor decisions. I have worked to be rehabilitated,” Collins said. “Now, I am just ready to make a life.”

Capitol News Illinois is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news service covering state government. It is distributed to hundreds of print and broadcast outlets statewide. It is funded primarily by the Illinois Press Foundation and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, along with major contributions from the Illinois Broadcasters Foundation and Southern Illinois Editorial Association.