The Field Museum’s dinosaur exhibits feature some of the largest creatures ever to walk the earth, but Sue the T. Rex and her statuesque kin are positively dwarfed — at least in terms of sheer numbers — by another class of species.

Insects account for an estimated 12 million individual specimens within the Field’s vast collection, the majority of which are beetles.

To put the dominance of beetles into perspective: The group known as weevils — beetles characterized by long snouts — contains 60,000 identified species, which is about the same as the total number of all vertebrate animals combined.

And the diversity within this group is astounding, said Bruno de Medeiros, who joined the Field in fall of 2022 as assistant curator of insects.

“They are super different to each other, we just don’t know in general because they’re too small for us to notice. They are as different as you are to a lion,” said de Medeiros.

Despite their abundance, beetles aren’t well studied, something that could be said of insects in general.

“First, it’s the size of the problem,” de Medeiros said. “We know one million insects, and there are another 10 million insects we haven’t put names to.”

De Medeiros is on a mission to fill some of that knowledge gap.

Video: Bruno de Medeiros, assistant curator of insects, displays some of the Field Museum's vast beetle collection. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Sometimes, during the course of a research project, scientists find exactly what they’re looking for. And sometimes they don’t find what they’re not looking for.

In the case of beetles, no one’s really looking for them to be pollinators, de Medeiros said.

“Even people who work on pollination don’t usually consider weevils as one of the main pollinators, and people who work on weevils don’t usually consider pollination as something relevant to the group,” he said. “There are lots of important things that people are missing because of preconceptions.”

One of those blind spots could have cost the world Nutella.

Palm oil, a product of the oil palm tree, is a key ingredient of the popular hazelnut spread, among a host of other foods including peanut butter.

When the oil palm tree, which is native to West Africa, was exported to other tropical regions for cultivation, growers were stumped by their lack of success. Productivity was hit or miss until it was discovered that the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) isn’t completely wind pollinated as thought but rather relies in part on the African oil palm weevil (Elaeidobius kamerunicus).

Following this breakthrough, the weevils were introduced to industrial palm oil production plantations in India, Malaysia and South America.

“We have the preconception that weevils are harmful, until people started finding these incredibly intricate pollination systems,” said de Medeiros.

In partnership with a pair of collaborators in France, de Medeiros combed through the scientific literature and came across hundreds of such relationships between weevils and plants, relationships that are every bit as intertwined as the well-publicized one between monarch butterflies and milkweed. In many cases, the relationships are even more dependent, with some weevils relying on a single plant partner throughout the insect’s life cycle, from egg-laying to the sole source of food for larva and adults.

Yet while monarchs have become a poster child for conservation efforts, weevils remain saddled with a reputation as destructive pests rather than recognized as pollinators. And this holds true not just among the general public but the scientific community.

De Medeiros said he was surprised recently to read a study of a member of the palm family in which researchers found no evidence of weevils as pollinators. Scientists had documented butterflies and bees approaching the plant’s flowers, but no weevils. Considering the known link between weevils and the oil palm, de Medeiros questioned the results.

So he studied the same plant, but came at it from the mindset that weevils should be present. He wrapped a flower in netting and returned a day later to remove the covering. It contained loads of weevils, which had been hiding inside the plant’s nooks and crannies and only emerged at night — something that prior observation of the plant, conducted externally, during the day, hadn’t revealed.

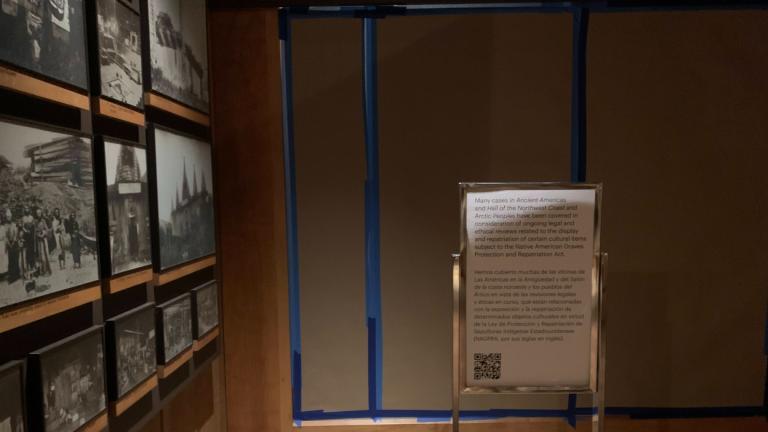

The Field Museum’s insect collection — drawers of specimens tucked away in storage. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Getting his peers to reorient their thinking about weevils is one reason de Medeiros and his collaborators published their review of the literature on weevils as pollinators.

“We hope that by summarizing what we know and providing some pointers on what we should be paying attention to, we can help other researchers and the public to better appreciate the role of weevils as pollinators, especially in the tropics,” he said.

The danger in continuing to ignore or underestimate the value of weevils is that they’re often the target of extermination campaigns, said de Medeiros, and indiscriminate killing could eliminate an important pollinator before its role within an ecosystem is known or understood.

He likened it to playing the game Jenga blindfolded and unwittingly removing a block from a teetering tower that’s actually supporting the entire structure.

Consider “No-See-Ums,” he said, the biting flies that humans would gladly wipe off the face of the planet. As pesky as they are, they also happen to pollinate the cacao tree.

“So we can’t get rid of them,” he said. “It would be nice if people would start appreciating them.”

Given how much humans have interrupted or destroyed natural pollination systems, there’s a heightened sense of urgency to the work of scientists like de Medeiros.

“In the past, things just worked,” said de Medeiros, meaning nature took care of itself. Today, nature is sending out an S.O.S.

The collapse of honeybee colonies was the wake-up call heard around the world, he said, but attention should also be directed to bees’ lesser-known, less charismatic counterparts.

“If we don’t know what other pollinators are doing, we might not be able to act” to save them, said de Medeiros. “We need the full picture.”

Part of that picture includes not just what beetles are doing today, but what role they played in the past. This is where the Field Museum’s specimens come into play.

De Medeiros pulls out one of the collection’s hundreds of drawers studded with beetles, some as small as the pinheads on which they’re affixed. He points to a speck barely visible to the naked eye. It’s pollen.

Using technology including DNA analysis, he’ll be able to determine what plant species this particular beetle had been visiting when it was snatched for scientific study. He can take that information and compare it with what, if anything, is known about this beetle’s habits in the present.

“When I look through evolutionary time, one thing that we observe is that actually there must have been switches, there must have been instances in which the beetles were interacting with a certain plant and at some point they shift to another one,” de Medeiros said. “So part of it is understanding what happens when those shifts happen, and how often do they happen. Because we don’t observe them in our time. Now everything seems very stable, but they’re not when you look through evolutionary time. So that gives us also a broader understanding of how interactions arise, how they are maintained, when do they shift.”

Answers to these questions could help scientists predict the impact of climate change on specialized relationships like that between the oil palm and the African oil palm weevil.

“Those weevils don’t have a choice. They only know one plant and everything that happens has to happen between those two partners,” de Medeiros said. “When things change, then the association between pollinator and plant might break down.”

Unlocking the secrets within the Field’s collection will be no small task.

“Except for a few things here, almost everything that you’re looking at are species that don’t have a name, and no one has worked on them scientifically before,” de Medeiros said.

Indeed, roughly half of the museum’s estimated 12 million insect specimens are still suspended in test tubes, awaiting sorting and curation.

“It’s actually impossible for us at the moment to count everything that we have,” he said, which is where artificial intelligence enters the conversation.

High-resolution images of specimen drawers can be fed through a computer, not just for counting but to take measurements or identify colors, at far faster speed than humans could accomplish.

Even with an assist from AI, de Medeiros has his work cut out for him.

“Getting this better organized and knowing more about the evolution of those beetles is on the to-do list for the next few years,” he said.

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]