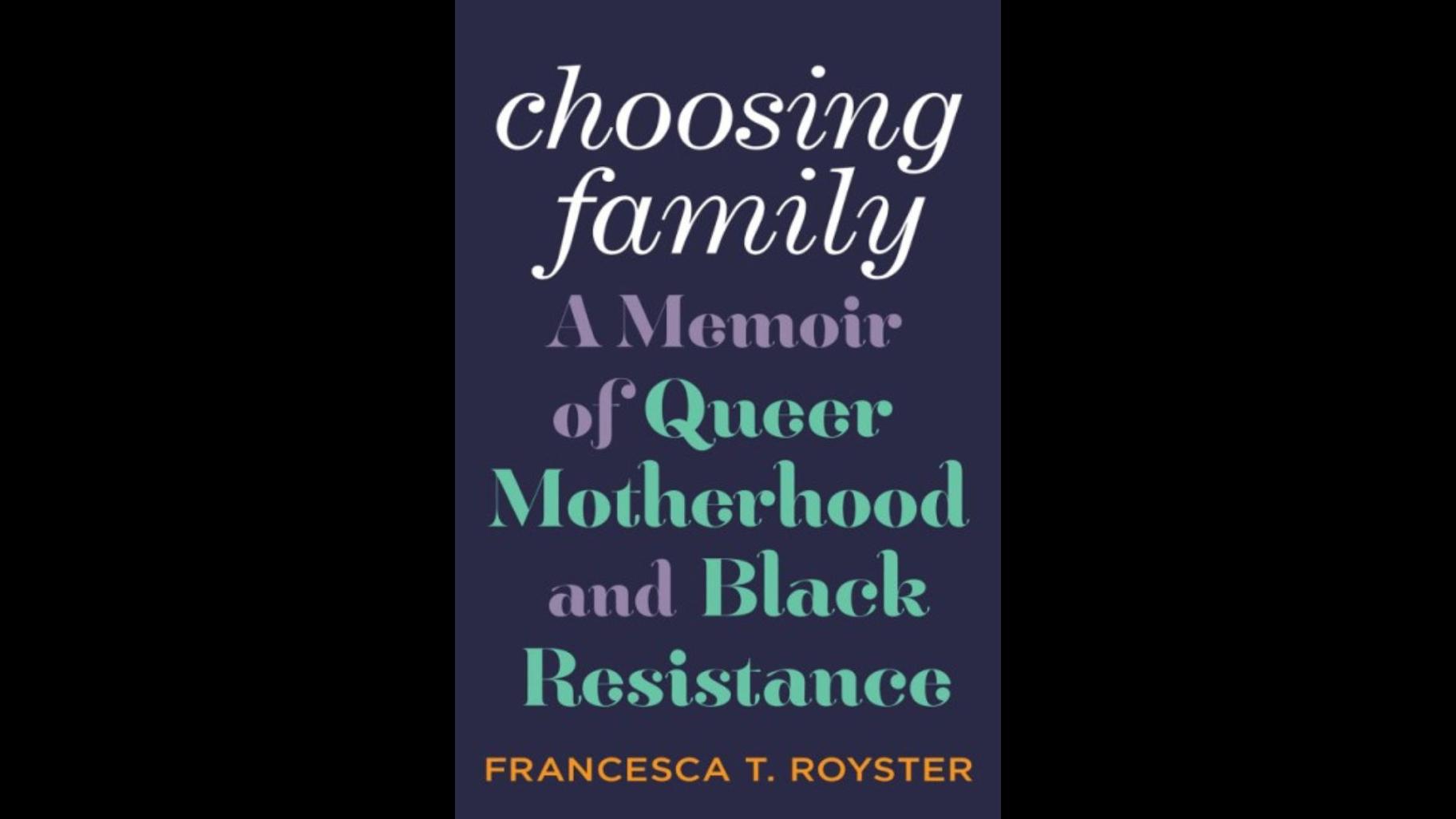

In her new book, Francesca Royster describes the moment she knew she wanted to be a mother as a transcendent experience watching a mother holding her sleeping child on an airplane. But the DePaul University professor’s path to holding her own child as a queer Black woman in her 40s was a little bumpier than that beatific moment. In this month’s Black Voices Book Club selection, “Choosing Family: A Memoir of Queer Motherhood and Black Resistance,” Royster relates her experience of becoming a mother through a lens of her own family’s history, including her great-grandmother Cillie.

“She was someone who came up from Louisiana from New Orleans with her mother and ended up running a boarding house in Bronzeville in the 1930s and ‘40s and actually up until the ‘60s,” Royster said. “I’m really interested in that idea of chosen family as one that is about connections, about making a way out of no way, about playing to your strengths and making home with the people who need it. And so that boarding house was sometimes with strangers or near strangers or distant relatives or sometimes actually with my own mother. So, it was a way of opening up home across different kinds of relationships.”

Royster and her wife adopted a baby girl, whom they call Cece, in 2012. The book recounts their path to deciding upon formal adoption to expand their family, but Royster said in the Black community, it’s not uncommon to informally adopt children when needs arise.

“I think we’re so often so busy kind of surviving, that adoption and some of the opportunity to build family isn’t really the one that’s the first thing that occurs to us often,” Royster said. “I think in times of crisis, we have stepped in to take care of the people in the neighborhood or take care of people in our own families. I think there’s also sometimes suspicion of the state and just kind of not until recently kind of being ignored by some of the agencies that do adoption. And so I think we as a culture have other ways of kind of taking care of each other’s children, looking out for each other. Sometimes it’s temporary, for a summer, for a year or a couple of years, and sometimes it’s really to be invested in people’s growth and lives and making sure they get their education throughout.”

Royster also described the understanding she and her wife had to develop about the trauma inherent in any adoption.

“It was really something that was underneath the surface in terms of thinking about, especially as we were wrestling with ways of adoption, thinking about what it meant, for example, to step in a fostering situation,” Royster said. “I really thought about that loss that to me became much more clear, but I didn’t really think about it in terms of reckoning with our own grief, reckoning with a birth family’s grief. And really wanting to have a relationship with a birth family means acknowledging … the process of adoption, the impact of that. And then, my child’s own grief as well, like the ways that even in providing a loving, really kind of wide-ranging family, there are ways that she’s had to wrestle with the realities of being adopted. And also the pressure of talking to people when she doesn’t necessarily want to about adoption as well.”

Royster dedicated the book to her daughter, who is 11 years old, and she said she hopes reading the book will help her daughter understand that her adoption was a labor of love.

“I hope that what she feels is just a sense of pride and just a reinforcement of the deep love that we have for her and the fact that, you know, we went through a lot in order to create our home for her and to sustain that,” Royster said.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

“Choosing Family: A Memoir of Queer Motherhood and Black Resistance” by Francesca T. Royster.

“Choosing Family: A Memoir of Queer Motherhood and Black Resistance” by Francesca T. Royster.

THE FRIDAY WE BEGAN TO think of ourselves as mothers started with a series of signs and wonders: a Banksy-style painting of a child lifted by a red balloon stenciled on the wall of a down- town construction site as we walked from the El; a toddler in a spring-green knit cap who popped his head over the back of our yellow booth at our favorite breakfast place, waving at us shyly. Chicago Aprils could give you anything—rain, hail, fog, snow—but the day was miraculously warm, with a steady sun.

I had an important meeting that morning with the promotion committee at my university to consider my application for full professor, and my partner, Annie, had come to hold my hand. Despite the years of hard work and preparation for that day—teaching, researching and writing books and articles, volunteering for hours of committee work—my mind was preoccupied with what I hoped would be a much bigger milestone.

Four months previously, Annie and I had turned in our photobook so that birth parents could consider us to become adoptive mothers. In that photobook, we tried our best to represent our strengths: two seasoned older women, one Black, one white, who loved each other and wanted to raise a child and to bring that child into our community of family and friends—our chosen family. We tried to present ourselves as we are: caring and goofy. We wore our hearts on our sleeves. Somehow, we hoped, the book would communicate our passion to become mothers. Then, three weeks before my meeting, we got a nibble. Our social worker, Wendy, showed us a photograph of a beautiful baby girl who had just been born, her face mostly cheeks and shining eyes. Her birth mother was considering us, among others. At a giddy breakfast brain- storming session, Annie and I gazed at the photo and came up with the name Cecelia, if we were chosen. (At first, I really pushed for the name Jesse. No one would mess with Jesse! I pictured her leaning against a brick wall, thumbs in the loops of her jeans. But in the end, it had to be Cecelia, graceful, ringing, and true.)

Before my promotion meeting was scheduled to start, we quickly ducked into Walgreens for last touches: a bottle of water, lip gloss, and breath mints. Standing in line, we heard Simon & Garfunkel’s song, “Cecilia (You’re Breaking My Heart),” playing on the loudspeakers.

“That has to be a sign! We’re going to hear something about the baby, for sure!” Annie called out, doing a little dance.

**

THIS IS A STORY ABOUT losses as well as miraculous gains. This is a story about beginning motherhood in the second half of our lives. So it’s about sore backs and knees, about making mistakes when we thought we should know better, and about the unspoken worry that we might not live to see our grandchildren. But it’s also a story of second chances and rebirths. This story is set in Chicago in the first decades of the twenty-first century, so it reflects the gentrification, racism, continued homophobia, and transphobia taking place in that city. But it’s also about making sense of the past and about creating home right where we’re planted. This is a story about building a chosen family, which means trusting friends to love you like family. This is a story about queerness and, because of that, it’s about yearning for the world that we want to have, but don’t yet.

I am writing this in a time of reckoning, when protests for Black liberation in the wake of the violent deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Ahmaud Arbery, Nina Pop, Tiara Banks, Jada Peterson, Remy Fennell, and so many others have demanded that the nation and the world face the continued history of white supremacy and the urgent need to change it. I am writing at the time of the coronavirus pandemic, which has reminded us all of the fragility of human life and of our own social safety nets.

It has also forced us to face the uneven playing field of access to health care, food, and shelter, those very basic and essential aspects of survival. This uneven playing field is also relevant to the role that adoption plays in our society. Motherhood has been one way to change the narrative of the disposability of Black life. We are rewriting the story, claiming the joy that the others—society, our family sometimes, even our own inner voices—said wasn’t meant to be ours.

This is our story.

Reprinted by permission of Abrams Books. Excerpted from Choosing Family: A Memoir of Queer Motherhood and Black Resistance by Francesca T. Royster. Copyright 2023 Francesca T. Royster. All rights reserved.