At the height of his political power, Ald. Ed Burke joked that there were three ways for members of the Chicago City Council to leave.

The ballot box. The pine box. The jury box.

But Burke, 79, is likely to complete his 54 years as a City Council member without any of the pomp and circumstance that once would have greeted his departure from his beloved City Hall, which he ruled with an iron fist for decades.

Burke is set to cast his final votes on Wednesday as the City Council member responsible for representing the Southwest Side’s 14th Ward. Burke did not run for reelection, and will be replaced by Jeylu Guiterrez, who was born 20 years after he first took office, on May 15.

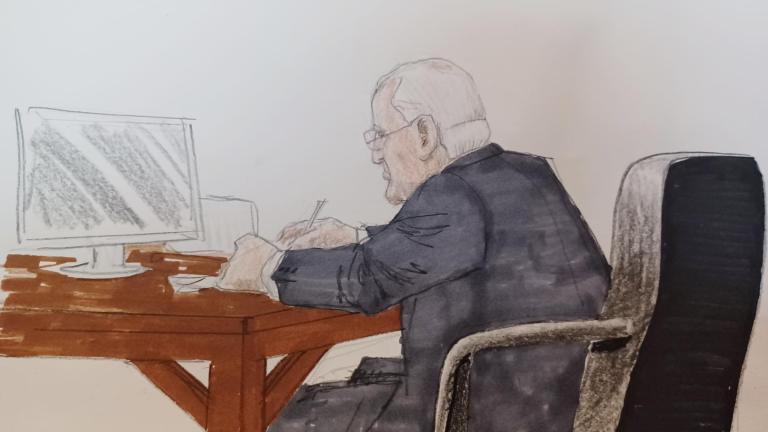

Burke’s career will come to an end under the shadow of a 14-count indictment alleging the powerful politician repeatedly — and brazenly — used his elected office to force those doing business with the city to hire his private law firm. Burke has pleaded not guilty, and used millions of dollars of stockpiled campaign cash to fund his defense.

The jury box awaits.

Once Among the Youngest, Now the Oldest

Before becoming the longest serving alderperson in Chicago history, Burke was one of the youngest people to be elected to the City Council.

Tapped to replace his father, Joseph, after his death from cancer in 1968, as the 14th Ward’s Democratic committeeperson, Edward M. Burke — as he would be known on official city stationery — went on to win a special election to replace his father when he was just 26, giving up his job as a Chicago Police officer.

Burke was sworn into office by former Mayor Richard J. Daley on March 14, 1969 — more than four months before American astronauts would land on the moon and take a giant leap for mankind.

Within a few years, Burke joined forces with Ald. Ed Vrdolyak (10th Ward) and the two made themselves thorns in the side of the old guard. Known as the Young Turks, the two led a group that plotted ways to seize power as part of a push that became known as the Coffee Rebellion.

But by 1980, Burke was perhaps tired of being an alderperson, best known for passing an ordinance that outlawed nudity in massage parlors and keeping a ban in place on pinball machines.

With the support of then Mayor Jane Byrne — another thorn in the side of the Daley machine, now struggling to recover from the death of Richard J. Daley — Burke ran for Cook County state’s attorney, only to lose to the boss’ son, Richard M. Daley.

That meant Burke was still an alderperson — but now a veteran, well versed in parliamentary procedure — when Harold Washington defeated not just Byrne, Burke’s pick for mayor, but also Daley in 1983. When Chicago’s first Black mayor got to City Hall, Burke was waiting, and ready, to thwart his every move.

Led by Vrdolyak and Burke, a group of 29 White City Council members worked to stymie Washington and his agenda, touching off what came to be known as Council Wars. That lasted until 1986, when a federal judge ordered that the city’s ward map be redrawn because it disenfranchised Black and Latino Chicagoans.

After a special election, Washington’s supporters controlled 25 of the 50 seats in the City Council, allowing Washington to end the stalemate with his tie-breaking vote.

Washington died in 1987, shortly after being reelected.

With a special election for mayor set for 1989, Burke set his sights on the big chair in the Council Chambers — but once again was steamrolled by Richard M. Daley, who reclaimed his father’s seat for his family, and his political machine.

Burke made do as chair of the City Council's powerful Finance Committee, a perch he kept for all 22 years Richard M. Daley served as mayor. That gave Burke the ultimate power over city subsidies, high-profile pieces of legislation and the city’s workers’ compensation program, which he ran behind closed doors.

Burke spent his time working to pass a ban on smoking in public places, and pushed through a measure that raised the age to buy cigarettes to 21, years before those laws would go nationwide.

Burke ran the monthly meetings of the City Council, frequently delivering stemwinders and soliloquys from the center of the Council Chambers about his favorite subjects: the city’s history, political conventions in Chicago, the heroism of law enforcement and the valor of the American military — even though he received a deferment that enabled him to avoid serving in Vietnam.

At the same time, Burke worked as a property tax attorney — representing future President Donald Trump as he sought breaks on the newly built Trump Tower along the Chicago River.

Between 1970 and 2023, Burke never missed a City Council meeting, even skipping a 2018 audience with Pope Francis with Burke’s wife, Illinois Supreme Court Justice Anne Burke, who was being honored for helping to found the Special Olympics.

That changed on Nov. 30, 2018, when FBI agents raided Burke’s City Hall and ward offices, carting away boxes of evidence and serving notice that the powerful politician was firmly in the crosshairs of the Department of Justice.

While running for a 14th term in office, Burke was charged with attempted extortion, accused of holding up permits requested by the owners of a Burger King in his ward until they hired his private real estate tax firm. Burke pleaded not guilty, and stayed in the race — setting off a political earthquake that led to the election of Lori Lightfoot to replace former Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who did not run for a third term, beset by his own problems.

After Burke’s arrest, Emanuel forced him out as chair of the Finance Committee, and launched an audit of the city’s workers’ compensation program. In 2020, Burke lost his position as the Democratic committeeperson for the 14th Ward, a position he had held since 1968, after his father’s death.

But while that earthquake derailed the political careers of his allies and friends, it did not stop Burke from winning another term, putting him on a collision course with Lightfoot, who used Burke as a symbol of the corruption she vowed to root out. Since 1969, 37 members of the Chicago City Council have been convicted of a crime.

But before Lightfoot and Burke could do much more than exchange barbs, federal prosecutors threw the book at Burke, hitting him with 14 criminal charges, including racketeering, bribery and extortion. Racketeering charges — usually brought against members of the mob or street gangs — allege a pattern of corruption unknown to its victims.

Former Ald. Danny Solis (25th Ward), who admitted taking bribes while chair of the City Council’s Zoning Committee, is set to be the star witness against Burke.

Soon after Burke pleaded not guilty, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the federal court system, delaying Burke’s trial for more than four and a half years after his indictment.

As Burke receded even further into the shadows at City Hall, he spoke most often only to cast a routine affirmative vote or to register his dissent to whatever initiative Lightfoot had put forward. But every so often, Burke could not resist rising to address his colleagues from his new aisle seat on the floor of the Council Chambers where he was shuffled after being charged with a crime.

One occasion was the celebration of the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 80th birthday in October 2021. As his colleagues paid tribute to the trailblazer, Burke recalled Jackson’s successful 1999 negotiations that led to the release of three U.S. soldiers taken prisoner by Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic, who would later be charged with genocide.

As Jackson got off the plane, reporters asked Jackson how he was able to win the soliders’ release.

Jackson was ready with a quip: “It was easy to negotiate with Milosevic, it’s Vrdolyak and Burke I have trouble with.”

As he delivered Jackson’s punchline, Burke turned to his colleagues, a broad smile on his face, as awkward laughter rippled through the chamber as the realization that Burke had just compared himself to a genocidal maniac washed over his colleagues during a birthday tribute to an ailing Civil Rights icon.

A Glimpse of What Could Have Been

Burke has not spoken to the news media since quietly declining to run for a 15th term in November.

But in 2018, Burke got a glimpse of what he must have thought it would be like when he decided to leave the City Council, free of the ballot box, jury box and not in a pine box.

To mark the 50th anniversary of his election to the City Council, Chicago’s movers and shakers gathered for a lunch hosted by the City Club of Chicago and to hear Burke look back on his time in office.

But before Burke strode into the spotlight, gold watch and cufflinks flashing in front of a large picture of a much younger Burke, then Mayor Emanuel introduced the alderperson, calling him chairman and a “walking encyclopedia of Chicago history.”

Burke did not mention Council Wars, or his failed bids for higher office. Instead, he celebrated officially clearing Catherine O’Leary and her cow of starting the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

And then Burke waxed nostalgic, saying he considered himself lucky to have had a “front row to history,” and perhaps gave listeners a clue as how he hoped to be remembered.

“History will conceive there have been plenty of rascals who saw Chicago as an opportunity to make a quick score,” Burke said. But the City Council also has been filled with “many more statesmen who furthered the interests of this city quietly and with great dignity.”

For Burke, that judgement awaits the decision that will be rendered by 12 people destined for a jury box at the Everett M. Dirksen U.S. Courthouse on Nov. 6.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]