Tariq Naseem, imam for the Zion Ahmadiyya Muslim community, stands for a portrait in the newly constructed Fath-e-Azeem mosque in Zion, Ill., on Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Tariq Naseem, imam for the Zion Ahmadiyya Muslim community, stands for a portrait in the newly constructed Fath-e-Azeem mosque in Zion, Ill., on Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

ZION, Illinois (AP) — A holy miracle happened in Zion 115 years ago. Or so millions of Ahmadi Muslims around the world believe.

The Ahmadis view this small-sized city, 40 miles north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan, as a place of special religious significance for their global messianic faith. Their reverence for the community began more than a century ago — with fighting words, a prayer duel and a prophecy.

Zion was founded in 1900 as a Christian theocracy by John Alexander Dowie, an evangelical and early Pentecostal preacher who drew thousands to the city with his faith healing ministry. The Ahmadis believe their founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, defended the faith from Dowie’s verbal attacks against Islam, and defeated him in a sensational face-off armed only with prayers.

Most current residents may not have an inkling of that high-stakes holy fight of a bygone era. But, for the Ahmadis, it is one that has created an eternal bond with the city of Zion.

This weekend, thousands of Ahmadi Muslims from around the world have congregated in the city to celebrate that century-old miracle and a significant milestone in the life of Zion and of their faith: The building of the city’s first mosque.

Dowie was born in Scotland in 1847. His family immigrated in 1860 to Australia, where he was ordained and became pastor of a Congregational church.

Dowie left Australia in 1888 for the United States where he grew in popularity with his healing ministry. Stories of Dowie’s miracles abound, including one about Sadie Cody, a niece of Buffalo Bill Cody, a celebrity known for his Wild West Show, who said her spinal tumor was healed by Dowie’s prayers.

With money accumulated from the faithful, Dowie bought 6,000 acres of land in Lake County, Illinois, hoping to establish a Christian utopia. Dowie’s laws forbade gambling, theaters, circuses, alcohol and tobacco. He also banned swearing, spitting, dancing, pork, oysters and tan-colored shoes. Whistling on Sunday was punishable by jail time.

The massive 8,000-seat Shiloh Tabernacle, built in 1900, became Zion’s religious center. It was there that Dowie appeared with his flowing white beard, robed in the brightly embroidered garments of an Old Testament high priest, and declared himself “Elijah the Restorer.”

While he welcomed Black people and immigrants into Zion, Dowie had harsh words for politicians, medical doctors and Muslims, which he expressed in his journal.

In 1902, Dowie wrote: “This is my job to gather people from the East and West, North and South and inhabit Christians in this Zion City as well as other cities until the day comes when the Mohammedan religion is totally wiped out of this world. Oh God show us the day.”

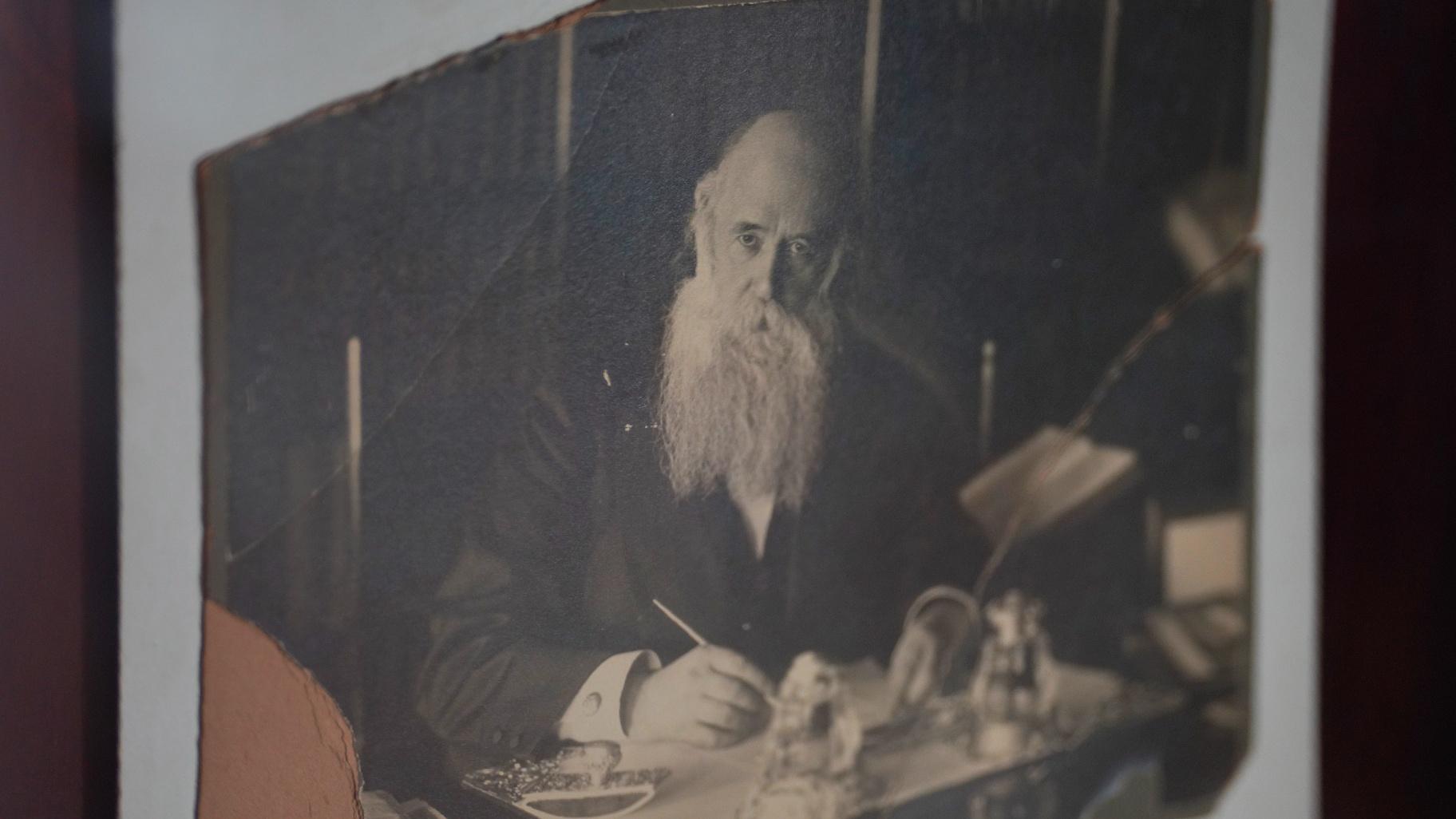

An archival photo of John Alexander Dowie, a Christian faith healer and the founder of the Zion as seen in the Historic Shiloh House in Zion, Ill., on Saturday, Sept. 17, 2022. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

An archival photo of John Alexander Dowie, a Christian faith healer and the founder of the Zion as seen in the Historic Shiloh House in Zion, Ill., on Saturday, Sept. 17, 2022. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

In his palms on a recent September day, Tahir Ahmed Soofi cradled a crumbling, yellow newspaper from the 1900s bearing Dowie’s image.

“Dowie is a part of our history, too,” said Soofi, president of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community's Zion chapter, as he arranged these relics in glass displays that will become part of the new mosque’s museum. The community has named this mosque Fath-e-Azeem, which means “a great victory” in Arabic.

The $4 million building, with a large prayer hall and plush carpeting, will replace their older, retrofitted center less than two miles away, which has been the community’s home since 1983.

As he got the new space ready for the Oct. 1 inauguration, Soofi recounted the tale passed down to generations of Ahmadis. When Ahmad, the religion's founder who lived in Qadian, India, heard about Dowie's angry proclamations against Muslims, he urged him to stop, Soofi said.

Ahmadis believe that their founder, who was born in 1835, was the promised reformer the Prophet Muhammed predicted and the metaphorical second coming of Jesus Christ.

Soofi said when Dowie ignored Ahmad's pleas, in 1902, he challenged Zion’s founder to a “prayer duel.”

In The New York Times and other U.S. publications at the time, this challenge was built up as a battle between two messiahs – to ascertain who was the true prophet and which was the true religion. Ahmad asserted in writing that, “whoever is the liar may perish first.”

Dowie refused to acknowledge Ahmad’s challenge and scoffed at his statements that Jesus was human, survived the crucifixion and lived out the rest of his life in Kashmir. He shot back writing: “Do you think that I should answer such gnats and flies?”

In the following years, Dowie’s fortunes began to fade. In 1905, one of his top lieutenants, Wilbur Voliva, took over leadership of the church after Dowie was accused of extravagance and misusing investments. Dowie’s health suffered thereafter. He died in 1907 after a paralytic stroke, at age 60.

While Ahmad died a year after Dowie passed, at age 73, his followers saw Dowie’s downfall and death as a great victory for their founder and faith.

For Ahmadis worldwide, the result of this prayer duel reaffirmed the truth of their messiah’s claims, said Amjad Mahmood Khan, U.S. spokesperson for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. It’s a story Ahmadi children grow up hearing at home and in their mosques worldwide.

“Whether you talk to an Ahmadi in Miami, Maine, South Dakota or Seattle, they will know this story and what a great victory it was,” Khan said, adding that it doesn’t mean they exult in Dowie’s demise. “It’s the triumph of what Islam stands for in the face of false allegations, and it’s about the victory of prayer over prejudice.”

The historic Shiloh House, now home to the Zion Historical Society, was once the home of Zion city founder and Christian faith healer, John Alexander Dowie, in Zion, Ill., Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022. Dowie had the 25-room mansion constructed in 1902 for $90,000. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

The historic Shiloh House, now home to the Zion Historical Society, was once the home of Zion city founder and Christian faith healer, John Alexander Dowie, in Zion, Ill., Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022. Dowie had the 25-room mansion constructed in 1902 for $90,000. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

“Welcome to Shiloh House.”

Kathy Goodwin, who volunteers every week at the 1902 Swiss-inspired chalet that Dowie built at 1300 Shiloh Boulevard, greets visitors with these words before she takes them around the 25-room mansion. Dowie spent $90,000 (about $3 million in today's dollars) to build it and $50,000 more to furnish it.

He brought fixtures from Europe, including a porcelain bath. The house had running water, electricity and phones, a rarity in that time.

Goodwin tells visitors about her family’s connection to Dowie. Her grandfather, a master carpenter from Switzerland, and his German wife went to hear Dowie speak in Chicago. Then and there, they decided to follow the preacher to Zion. Goodwin’s grandfather was chief carpenter for Shiloh House and her father, the last of 15 children, ran around the mansion as a child while his dad helped build it.

The house has numerous images of Dowie — painted, photographed and woven with lace. Dowie, who was 5-foot-2, had carpenters craft custom wooden step stools so he could reach the top shelves of his bookcases. The house even has on one wall, two framed pieces crafted with Dowie's hair by his barber. One shows the Dowie's greeting “Peace to thee” and another is a depiction of the Bible.

Goodwin is proud of Dowie’s legacy and wants it preserved.

“He believed in love, kindness, helping people,” she said. “I honestly believe people were healed here.”

She also believes Dowie, in his later years, “got carried away” and “did things with money he shouldn’t have.”

“But he paid for it,” she said. “I’m here because I want his story to stay alive.”

Goodwin also yearns to go back to a time when she was a little girl and the city played chimes at 9 in the morning and 9 at night.

“People stopped wherever they were and prayed,” she said. “I'm sorry it’s not like that any more.”

Mike McDowell’s great grandparents moved to Zion in 1905 from North Dakota because his great grandmother believed Dowie cured her whooping cough. McDowell sits on the board of the Zion Historical Society, which maintains Shiloh House. He is also a city commissioner and pastor at Christ Community Church, the remnant of Dowie’s original congregation.

McDowell says his congregation now identifies as evangelical and doesn’t adhere to Dowie’s teachings. But he credits the founder for innovative municipal planning.

“He came up with the idea of subdividing the community and making it self-sufficient,” McDowell said. “He created the city’s park system requiring every housing subdivision to have green spaces.”

McDowell said Dowie’s downfall began when “he started believing his own press and thought of himself more highly than he ought to have.”

He agrees what Dowie said about Muslims and Ahmed was “inflammatory,” but doesn’t believe the founder accepted Ahmad’s prayer duel.

“Both men had visions of grandeur about themselves,” McDowell said, “which probably weren’t appropriate.”

McDowell is happy to see the new mosque and lauds the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community for their many service projects in town, particularly food giveaways that were valuable to many during the pandemic.

Mike McDowell, a board member for the Zion Historical Society and an associate pastor at Christ Community Church, stands for a portrait in the Historic Shiloh House, once owned by the town’s founder, John Alexander Dowie. McDowell's great grandparents moved to Zion in 1905 from North Dakota because his great grandmother believed Dowie, a known faith healer, cured her whooping cough. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

Mike McDowell, a board member for the Zion Historical Society and an associate pastor at Christ Community Church, stands for a portrait in the Historic Shiloh House, once owned by the town’s founder, John Alexander Dowie. McDowell's great grandparents moved to Zion in 1905 from North Dakota because his great grandmother believed Dowie, a known faith healer, cured her whooping cough. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

Just as McDowell’s and Goodwin’s ancestors moved to Zion following Dowie’s healing powers, Tayyib Rashid moved with his family to the area last year from Seattle when plans for the new mosque came to fruition.

“You can’t have a Zion mosque anywhere else,” he said, adding that he feels a deep connection to the prayer duel and prophecy. “Dowie had all the means and resources. (Ahmad) had God on his side.”

For community member Suriyya Latif, the new mosque reflects the Ahmadi community’s motto, which is painted in giant letters on the wall of their community center: “Love for all, hatred for none.”

“People pull up to the parking lot and take selfies with that sign,” she said.

The prayer duel, she said, is not an archaic tale, but a current manifestation of the community’s motto. Latif, who has toured the Shiloh House, wishes Dowie could have seen what his faith had in common with Islam.

Dowie banned pork and alcohol in Zion, which are also commands in Islam. Even Dowie’s greeting “Peace to thee” is synonymous with the Muslim greeting “Salam alaikum.”

The Ahmadis have struggled to gain acceptance even among mainstream Muslims, adding to the significance of establishing the mosque in Zion, said national spokesperson Khan. Pakistan’s parliament declared Ahmadis non-Muslims in 1974.

Khan said the global Ahmadiyya community’s current leader and caliph, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, is in Zion to inaugurate the new mosque this weekend — a momentous occasion for U.S. Ahmadis. Ahmad was forced into exile from Pakistan after his election in 2003 and resides in London.

Members of the Zion Ahmadiyya Muslim community attend Friday prayer on Sept. 16, 2022, in Zion, Ill. The Ahmadi community will move from a suburban house, which was converted into a community center where the members pray, to a new multimillion dollar mosque in Zion. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

Members of the Zion Ahmadiyya Muslim community attend Friday prayer on Sept. 16, 2022, in Zion, Ill. The Ahmadi community will move from a suburban house, which was converted into a community center where the members pray, to a new multimillion dollar mosque in Zion. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

Over the years, Zion’s Ahmadiyya community has been buttressed by women who have assumed leadership roles, as well as African Americans who have accepted the faith in large numbers. About half of the community in Zion is African American.

Ahmadi women raised nearly half of the $4 million needed for the new mosque, said Dhiya Tahira Bakr, national president of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community's women’s auxiliary. Bakr, who is African American, converted to Islam nearly four decades ago. Transcending culture and language barriers has not been difficult because their faith has bound Ahmadis of all backgrounds together, she said.

“I didn’t grow up drinking chai or eating spicy food, but I enjoy it now,” Bakr said. “When you talk to one another, you forget about all that because you are bonding with the heart.”

The prayer duel and Dowie’s demise opened up a path in Zion for the Ahmadiyya Muslims to build on that foundation by serving the community, she said.

“We knock on doors and let people know that they don’t have to be afraid of us because we are Muslim or Black or Asian or whatever,” Bakr said. “It’s important we do this work for our children so we can dispel all these stereotypes.”

Mayor Billy McKinney’s family moved to Zion in 1962, as the civil rights movement was gathering momentum. For Black families, racially integrated Zion was an oasis in a nation where segregation was the norm, he said. The mayor believes a community partnership has emerged from this century-old feud.

Like many Zion residents, McKinney had not heard about the prayer duel and was initially surprised to learn about Dowie’s hostility toward Muslims.

He says now is the time to move forward in unity.

“History is history and I could take issue with anyone from the past if I wanted to,” McKinney said. “I’m about looking forward.”

The newly constructed Fath-e-Azeem mosque, which means “a great victory” in Arabic, in Zion, Ill., on Friday, Sept. 16, 2022. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

The newly constructed Fath-e-Azeem mosque, which means “a great victory” in Arabic, in Zion, Ill., on Friday, Sept. 16, 2022. (AP Photo / Jessie Wardarski)

The mayor will present Ahmad, the fifth successor to the sect’s founder who challenged Dowie, with a key to the city as a symbol of trust and friendship.

The Ahmadis are moving forward with the construction of their minaret, which they expect will be completed next year. The minaret is a global symbol of Islam and the faith’s call to prayer five times a day.

It would be a stark contrast from Dowie’s vision of a Christian utopia.

“The founding fathers of Zion are probably rolling in their graves,” said David Padfield, minister of Church of Christ, a non-denominational congregation around the corner from the mosque. “They didn’t even want our church here.”

Padfield, who supports the Ahmadiyya community, says it was the founders’ intolerance and exclusion of other faiths that “made it difficult for them to function.”

Soon, towering 70 feet above the ground, the mosque’s minaret will be the tallest structure in the city that Dowie built.