Economic sanctions. Collateral consequences. Permanent punishments. There are 44,000 restrictive federal laws, rules, and policies that continue to penalize people long after they have served their sentence in prison. Permanent Punishment, a four-part series, examines this stark reality faced by nearly 3.3 million men and women in Illinois.

You very likely have something in common with Marlon Chamberlain, a 46-year old suburban working dad.

He’s a father, a campaign manager at a nonprofit, a college student studying social work and a homeowner in Dolton. He and his wife, Ciera Bates Chamberlain, share eight children between the two of them.

It’s a long way from the life Chamberlain lived 25 years ago.

“I wake up every day, like it’s just a big celebration because every day I have an opportunity to build new relationships, to learn new things, to grow and, and for me, that’s what I love to do,” Chamberlain said.

Despite all of his success today, Chamberlain is still limited by mistakes he made long ago.

“I was arrested Sept. 25, 2002. I’ll never forget,” he recalls.

That arrest led to a conviction and more than 10 years in prison for federal drug crimes. He’s been out of prison for nearly decade.

“I had no idea when I was sentenced to do time that the judge didn’t say, ‘Even once you’re released, there’s interest that you have to pay on this debt,’” Chamberlain said. “No one ever told me that.”

The “interest” he’s referring to are the myriad laws, rules and policies that people with criminal records must follow after they’ve been convicted, whether or not they’ve served time in prison.

After serving time in federal prison, Marlon Chamberlain now works with Heartland Alliance to reduce the legal barriers faced by people with criminal records.

After serving time in federal prison, Marlon Chamberlain now works with Heartland Alliance to reduce the legal barriers faced by people with criminal records.

In Illinois, an estimated 3.3 million people have criminal records, which can include everything from an arrest to years spent in prison. But even once that criminal case has run its course in the legal system — the punishment continues.

For example, Illinois code 720 ILCS 5/12-36 says, “It is unlawful for a person convicted of a forcible felony to knowingly own, possess, have custody of or reside in a residence with either an unspayed or unneutered dog…”

This law applies to people with cruelty to animal convictions, as well as those with drug or gun convictions.

Illinois code 430 ILCS 85 2-20 prohibits anyone convicted of sex-related or homicide-related offenses from working for a carnival or amusement park.

Anyone with a criminal conviction can’t enter a bingo hall.

“So if I’m somewhere with my auntie at the church, at a bingo game, I’m subject to where I could be arrested for being on the premises of a bingo game,” Chamberlain says.

But there are other laws that hit closer to home.

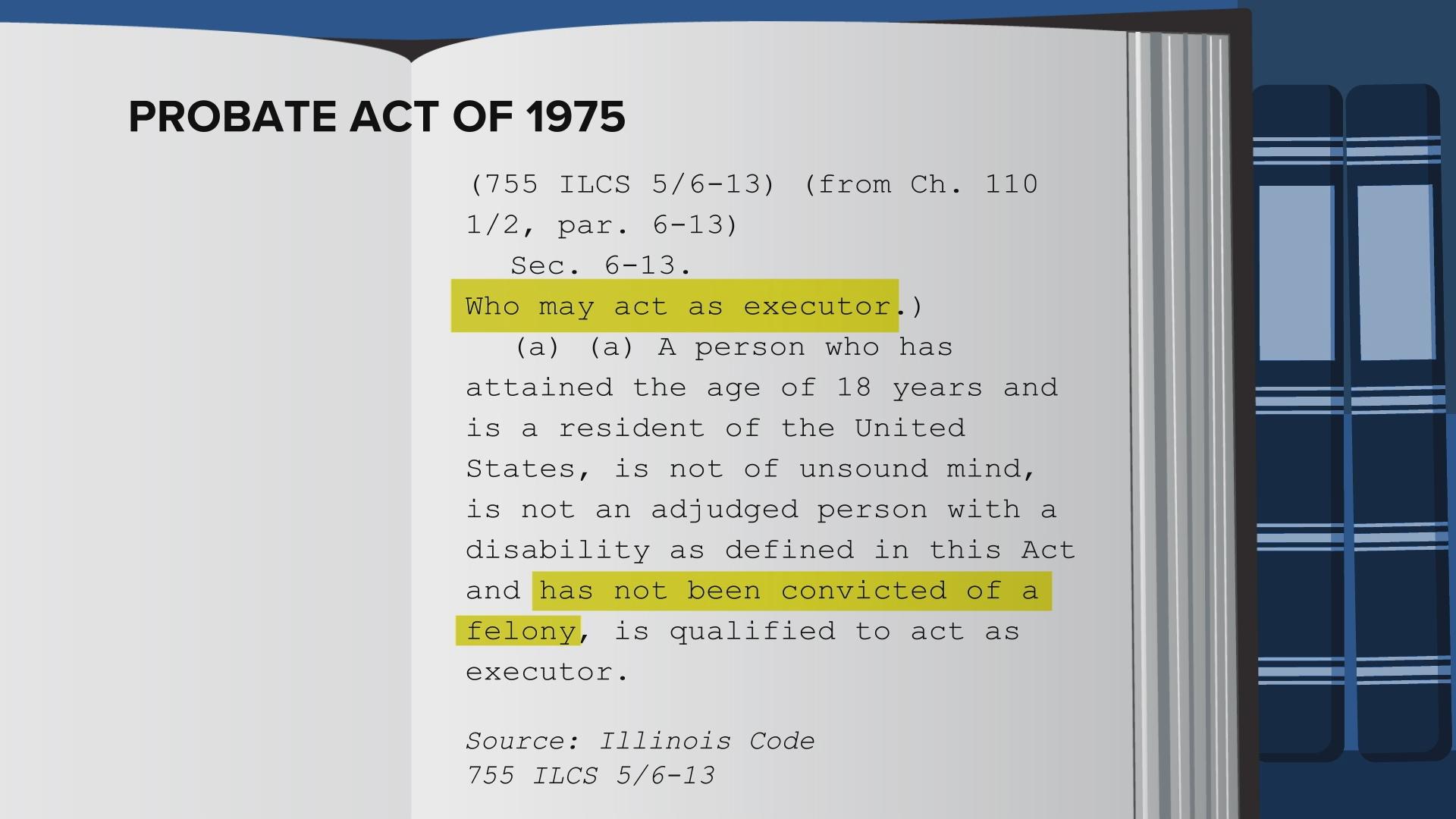

“Last year, my father passed away. He appointed me as the executor over his estate, but because of my 25-year-old conviction, I wasn’t able to carry out my father’s last wishes,” Chamberlain said.

The state’s 1975 Probate Act prohibits anyone with a felony conviction from serving as executor or administrator over an estate.

Chamberlain says it impacts more than 600,000 people in Illinois.

(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

He knows this because he runs the Heartland Alliance’s Fully Free campaign. It is an effort to unroll just some of the estimated 1,300 state laws that continue to impact people with criminal records, including the Probate Act.

Reuben Jonathan Miller, an author and associate professor at University of Chicago, calls it an alternate legal reality that only applies to this specific population.

“They return to a world in which there are 44,000 laws, policies and administrative sanctions that prevent people with criminal records from fully participating in the economy, from fully participating even in family life,” Miller said. “And 19,000 labor market restrictions in this country.”

Miller said that of the 44,000 laws across the 50 states, there are approximately 1,300 in Illinois alone.

Many of the laws pose not just an inconvenience but create situations that can lead to more crime, Miller said.

“The problem is that 100 years of criminological research tells us something quite simple: it’s that precarity leads to more crime. Precarity leads to more violence,” Miller said.

As examples of rules that lead to that uncertainty, he lists “things like housing instability, unemployment, limited access to medical care, substance abuse treatment when we break bonds, with people’s families.”

And these permanent punishments affect no small part of the population.

- In Illinois, an estimated three million of the state’s 12.7 million residents have criminal records. Half of them have convictions.

- A total of 548,000 Illinois residents have felony convictions.

- Nationwide, 19.6 million Americans are estimated to have a felony record.

“When there’s interest in a crime question, the response is always punishment,” Miller said. “The problem is that exclusion leads to more crime. Exclusion in fact, breeds more crime and more criminality.”

There are also the de facto laws. Those rules aren’t written into the legal code, but happen anyway, having a similar impact.

After his release from prison, Javier Reyes started his own nonprofit to help other formally incarcerated people return to Aurora. (WTTW News)

After his release from prison, Javier Reyes started his own nonprofit to help other formally incarcerated people return to Aurora. (WTTW News)

Javier Reyes, 52, initially struggled to find work and housing after his release from federal prison for conspiracy to commit bank robbery. He’s been out for two years.

“You can only live in certain areas when you have felonies and those are disenfranchised communities,” Reyes said. “If I was to go to St. Charles, Naperville, I couldn’t rent an apartment, they do background checks; versus if I go to anywhere in a low-income housing, they won’t do a background check, because that’s the kind of people they expect there. I tried to live in a good place, and I was turned down four times on applications.”

Today, Reyes manages the 20-unit building where he lives in Aurora. He works other jobs to pay his bills.

It gives him money and time to work on his own nonprofit, Challenge II Change.

The goal is to help others who are returning to Aurora to get back on their feet, too.

“Once you’re a felon it’s almost like you’re never forgiven. No matter how much time you do, you can never be vindicated,” Reyes says. “You’re not fully free. None of your rights are fully restored. No matter, I’m a taxpayer. No matter, I’m a law-abiding citizen. No matter, I’m a husband, a father — that felon trumps everything else.”

Reyes is in company with Marlon Chamberlain, who hopes his work with the Fully Free campaign will make change for the thousands of men and women facing permanent punishments.

“And so yes, I’m still impacted by decisions that I made years ago,” Chamberlain said. “But I’m also using my past to push forward and the things that I’ve learned to build relationships, to build a movement to create the world that we all want to see.”