Across Chicago, reporters and crime watchers utilizing social media have kept a close ear on police scanners, often relaying that information to the public.

Now, real-time police scanner information will be delayed by 30 minutes and will stream from a single online feed.

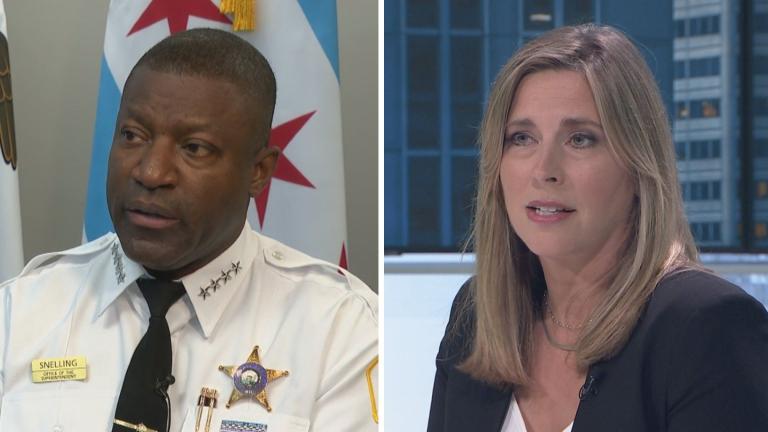

The Chicago Police Department has begun the process of encrypting its dispatch channels to avoid disruptions from outside the police system. But some are calling into question the need for the change, and cite potential issues of transparency.

Maira Khwaja, director of Public Strategy at Invisible Institute, shared her doubts of this new system.

“This is a worrisome change for me because it’s indicative of how the Chicago Police Department has been working backwards on transparency overall, which includes the city fighting back on the Freedom of Information Act requests,” Khwaja said.

Khwaja has listened to the police scanner and has used it to talk to journalists, inform activists, and even to stay aware of local police activity in her neighborhood.

“What is worrisome here is that we know that having encrypted and 30-minute delayed information of redacted audio takes away a lot of this utility of this very basic public tool…,” she said. “... This gives them more opportunity to obscure or craft narratives without oversight, so this is a huge step backwards.”

Ed Yohnka, director of communications and public policy for the ACLU of Illinois, believes there is no need for the move toward encryption, especially because there has been no public discussion on the matter.

“This is something that is simply happening in the city and around policing without a debate, without consideration, without any of us having a chance as residents and citizens to be able to weigh in on it,” Yohnka said.

He believes that people should be able to follow what is happening in their community in real time.

“Frankly there isn’t a reason that the public shouldn’t be able to do that,” Yohnka said. “The police, after all, are public servants. They serve the public. They serve all of the residents of Chicago.”

The city of Chicago did not make a representative available and instead provided a prepared statement.

“Having encrypted radios will provide added protection for communities and the personal information of victims, suspects, witnesses, and juveniles,” it reads in part. “It also will enhance officer safety and prevent suspects from gaining a tactical advantage by listening to live incidents and investigations.”

Despite many major cities across the country adopting this new system, Yohnka believes “we should stop and ask ourselves is it the right one for Chicago?”

Yohnka notes that the The Department of Justice has cracked down on the Chicago Police Department.

“One of the things that’s required for that reform to take hold is for transparency and for public trust,” he said. “This moves backwards.”

So far, CPD has transitioned six out of the nine radio zones and is yet to release the exact future transition dates for the remaining zones.