Audubon's Explorer platform illustrates migratory bird flyways in North America. (WTTW News)

Audubon's Explorer platform illustrates migratory bird flyways in North America. (WTTW News)

It’s a question that’s intrigued and confounded everyone from toddlers to post-doctoral researchers: Where do birds go?

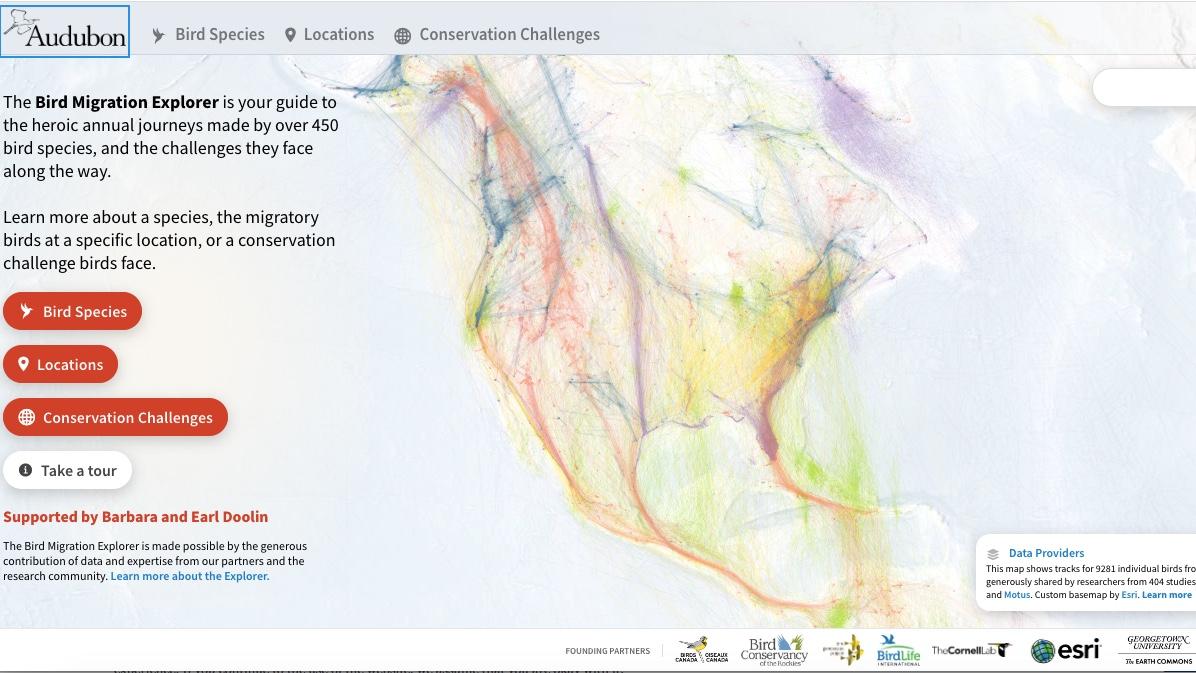

The Bird Migration Explorer, a new interactive digital platform launched Thursday by National Audubon Society, provides the clearest answer yet, just in time for fall migration season.

Developed by Audubon in conjunction with nine partner organizations, Explorer consolidates data that previously existed in hundreds of scattered pockets and brings it to life in dramatic visual fashion.

Users can trace the most heavily used migratory flyways, follow the journeys of more than 450 individual species and learn about the conservation challenges birds face along their routes. One of Explorer’s most impressive features is a tool that shows the point-to-point connections birds make between locations across the Western Hemisphere.

Choose a city like Chicago and watch as spokes radiate out from the hub, looking very much like an airline’s route map but representing infinitely more flights.

“It (Explorer) brings together puzzle pieces from different elements of migratory science,” said conservation ecologist Jill Deppe, senior director of Audubon’s Migratory Bird Initiative. “We’re taking a holistic look at what birds need and putting local actions into a hemisphere context, creating a sense of connection between faraway places.”

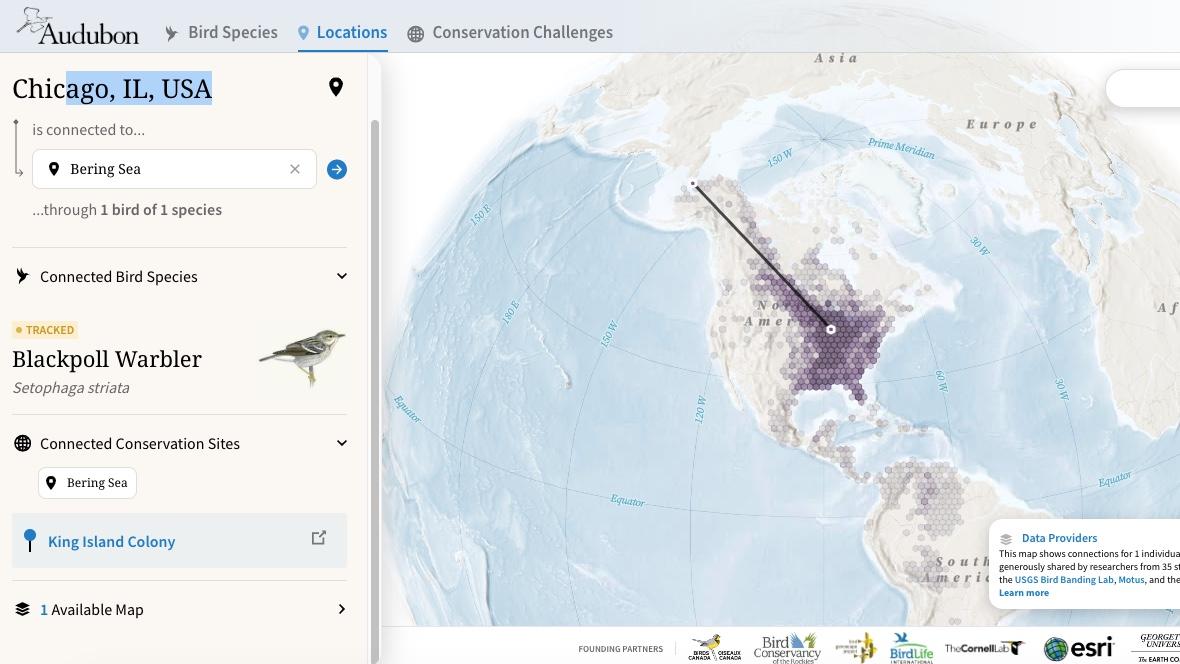

Take the blackpoll warbler, for example.

A typical map of the bird’s range broadly shows its wintering grounds fanning out across northern South American, its migration taking place over half of the continental United States and its breeding grounds covering almost the entirety of Canada and Alaska.

Explorer’s deep well of data allows users to zoom in with greater precision. Tracking devices have pinpointed the blackpoll at a sanctuary in Venezuela, then a migratory stop in Chicago, and finally a summer nesting home in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska.

Those links highlight the need for cooperative conservation efforts among the people, organizations and governments that touch locations used by birds at every stage of their journey.

“What happens in the arctic is going to impact the birds in Chicago,” Deppe said.

There’s a sense of urgency to Explorer’s launch, given the 2019 report that North America has lost 3 billion — or 30% — of its birds since 1970. Among the vanished, 2.5 billion were migratory birds, according to Deppe.

“We’ve been doing a lot of conservation and we’ve still lost so many,” she said.

One exception, she noted, was waterfowl, a group whose numbers actually increased. Deppe credited the collective, collaborative approach to the protection of wetlands for waterfowl’s success.

“It’s a good example to point to hemispherically,” she said. “It’s about making those connections and asking, ‘How do we work together?’”

Explorer's point-to-point feature: The tiny blackpoll warbler connects Chicago to the arctic. (WTTW News)

Explorer's point-to-point feature: The tiny blackpoll warbler connects Chicago to the arctic. (WTTW News)

One obstacle to making those connections was the formerly siloed nature of the information Explorer collected and has now shared.

Stephanie Beilke, senior manager of conservation science at Audubon Great Lakes, is among the researchers whose data has been incorporated into Explorer.

She always knew, she said, that a huge pool of data existed, but much of it was inaccessible. “You couldn’t get it unless you knew who was doing the research and how to contact them,” Beilke said.

Members of Deppe’s team made it their mission to comb the scientific literature for projects that involved the tracking of migratory birds. They spent years working the phones and obtaining permission from data holders like Beilke — nearly 300 individual researchers and institutions in total.

Layered on top of the science are observations uploaded by regular folks to the eBird platform. These millions of sightings populate Explorer’s “abundance” feature, which depicts how many of a bird species are present at a location at different times of the year.

“When people see those maps, they see themselves as contributing,” Deppe said.

Deppe expects Explorer to appeal to various audiences, from birders and the “bird curious” — all the people who became enamored with our feathered friends during the pandemic — to advocacy organizations, which will find Explorer’s mapping useful in terms of identifying where to focus attention on conservation and preservation.

The site also has the potential to unlock additional discoveries related to migration.

“It’s not every day we get a tool like this,” said Beilke.

While the bird lover in her has enjoyed navigating Explorer and looking at individual bird’s journeys, she said, the researcher in her is excited by the amount of legwork the site represents, putting all the results of those hundreds of previous studies at her fingertips.

“If I’m interested in filling a research gap, we can see what’s been done,” Beilke said. “I want to know where there are needs in the Great Lakes. Are there species of concern we need to track?”

According to Explorer, at least 136 species have some sort of connection to Chicago, which is plenty of fodder for scientific inquiry. Could the region support more? Conversely if the number declines, have we done something wrong, or does the responsibility lie elsewhere?

These are kinds of questions Explorer raises for researchers to investigate, Beilke said.

While the launch of Explorer represents the culmination of years of development, that work is by no means finished, Deppe said.

Creating a better experience for mobile users is a top priority, she said. As an acknowledgment of the project’s partners in Canada and Brazil, Deppe would also like to see the site translated into French and Portuguese, to complement the current versions in English and Spanish.

It’s a given that Explorer will be updated continually as new data becomes available.

“We are at the frontier,” Deppe said. “Migration is the last frontier.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]