MAT Asphalt in McKinley Park is pictured in a file photo. (WTTW News)

MAT Asphalt in McKinley Park is pictured in a file photo. (WTTW News)

In 2021, MAT Asphalt, located in Chicago’s McKinley Park neighborhood, accumulated the highest number of air pollution complaints of any address in the city, according to Chicago’s 311 system data.

However, local advocates say a lack of action by the city to educate residents about risks posed by the facility and a lack of adequate, real-time air monitoring left the community no choice but to act themselves.

In a city where air pollution is an environmental justice issue, disproportionately affecting communities of color and immigrant communities, local grassroots groups are self-installing, funding and monitoring air pollution monitors to understand the specific threats they face and demand change.

“A lot of people will come to the park from around the Southwest Side, to use it and to go for runs and to play tennis and do whatever,” said Anthony Moser, a founding member of Neighbors for Environmental Justice (N4EJ). “And there are folks who would want to know, to be able to make a decision like OK, if the air quality is really bad, I probably don’t want to go for a run over there right now.”

MAT Asphalt officials have long maintained that their plant produces well under the legal threshold of pollution, as monitored by the Illinois EPA, and has pollution control items in place.

Air monitoring has previously proved a help for residents looking to understand the type and scope of air pollution they face around the asphalt plant in McKinley Park, a metal shredder in South Chicago and various heavy industries in Little Village.

The city’s air pollution levels are currently being monitored at a local level with real-time emission measurements by two variations of air monitors, both installed and monitored by parties outside of city officials.

Gina Ramirez, Midwest Outreach Manager at Natural Resources Defense Council, recently took it into her own hands to install an air monitor outside her home in South Chicago, which lies just a block away from the Nickelson metal scrapper.

“I’ve always wondered, what are the impacts of [the metal scrapper and asphalt plants],” Ramirez said. “I don’t know what’s in this stuff. It’s pretty scary.”

Ramirez now collects her own data to ensure the city is held responsible for the impacts of these industries.

“I can just look at my monitor, call 311 and be like, ‘Hey, my monitor is picking something up. Can you get an investigator out there right now?’,” Ramirez said. “Which would take forever, but it’s a little bit more insurance instead of me just saying ‘I smell foul odor.’ They’re just [going to] say, ‘you’re crying wolf and we’re [going to] take our sweet time to get out there.’ It’s kind of like my word against theirs but with the air monitor it’s actually recorded.”

Grassroots organization N4EJ has self-installed, self-funded and currently monitors four PurpleAir monitors around McKinley Park, one by Davis Square, one in Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s neighborhood and others waiting for installation.

The PurpleAir brand monitors collect primarily particulate matter data, specifically PM 2.5, and allow the public to assess their local air quality against the overall air quality index in real-time. These microscopic air pollutants, which measure to be only a fraction of a strand of hair, can cause health problems by penetrating across the blood-brain barrier and infiltrating the lungs.

“An estimated 5% of all premature deaths in Chicago can be attributed to particle pollution,” a city of Chicago report states.

The second variation of air monitors, known as Project Eclipse, are installed and monitored by Microsoft. In July 2021, Microsoft Urban Innovation Research Group partnered with Array of Things, University of Chicago and JCDecaux Chicago to deploy 100 custom, low-cost air quality sensors on Chicago transit shelters.

While both monitors capture PM 2.5, the Eclipse sensors can also record carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone and nitrogen dioxide levels. Eclipse sensors also rely on cellular connectivity rather than Wi-Fi, unlike the PurpleAir monitors. That means the Eclipse sensors rely on minimal existing infrastructure. The Eclipse project also ensured easy accessibility by installing QR codes at every Project Eclipse bus stop to reach the project’s website, while PurpleAir monitors require consumers to find the website and location manually.

While N4EJ hopes these monitors will give residents more accurate measurements of real-time air pollution and impacts of MAT Asphalt, according to Moser, it’s hard to measure the true change in the air quality index since plant operations began because the air monitors were not collecting data before operations started, therefore there is no “baseline air quality” to measure from.

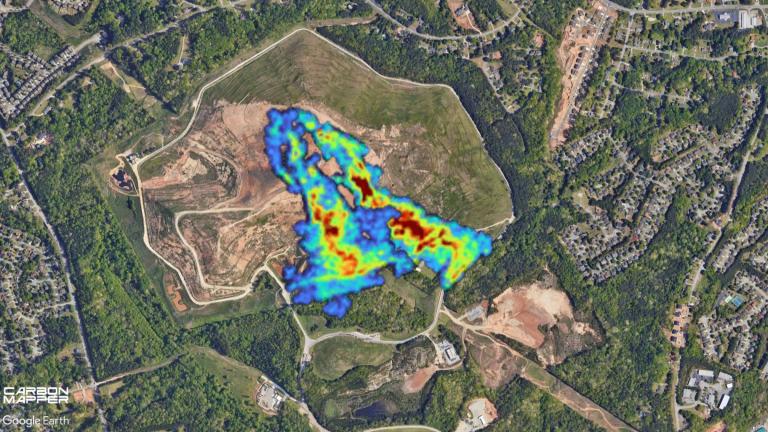

However, Moser says that some days when the plant is operating, “the air quality next to MAT was 20 or 30 points higher than even a few blocks away,” and “we’ve seen pollution spike on the air monitor as the plant started up” (as shown in this timelapse video).

In order to get more concrete data, Moser hopes to install fence line air monitoring, on-site, all around the facility, instead of community-based monitoring.

“As far as the city’s involvement, no, the city has not done anything to help with our air monitor situation,” Moser said. “They do not require air monitoring at MAT Asphalt or any of the other asphalt plants in the city.”

N4EJ puts an emphasis on educating residents, creating public conversations to hold sources of pollution accountable and forcing the city to acknowledge the risk of air pollution. Since air pollution is not a tangible or entirely visible hazard, many overlook the risk, according to the organization.

“It's something that’s like they might feel as kind of smoky out today or, you know, smells weird, whatever, but it does't necessarily feel quantifiable,” Moser said.

What can be quantifiable are the risks of the residents living in these regions.

Earlier this year, MAT Asphalt said the plant poses a low risk to community members since emissions are “one-twentieth of the allowable regulatory limit — and less than 1 percent of the permissible amount of particulate matter,” according to a news release.

Though, studies show that even air pollution levels that are below the EPA guidelines can pose significant risks and health impacts.

“A study just recently found that an increase of one microgram per cubic meter in an area was correlated with a 20% increase in the number of daily suicides, ” Moser said.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated impacts on academic performance for students living in regions of high air pollution.

Moser hopes that the data they have collected over the last year will allow community members to have a baseline air quality for future projects and help educate the community about the health risks in their neighborhood.

In the next year, N4EJ has plans to put up at least another half dozen air monitors around the city and is in discussion with other environmental justice groups to install more. However, since the project is entirely self-funded, N4EJ is currently waiting for more grant money to continue growing.