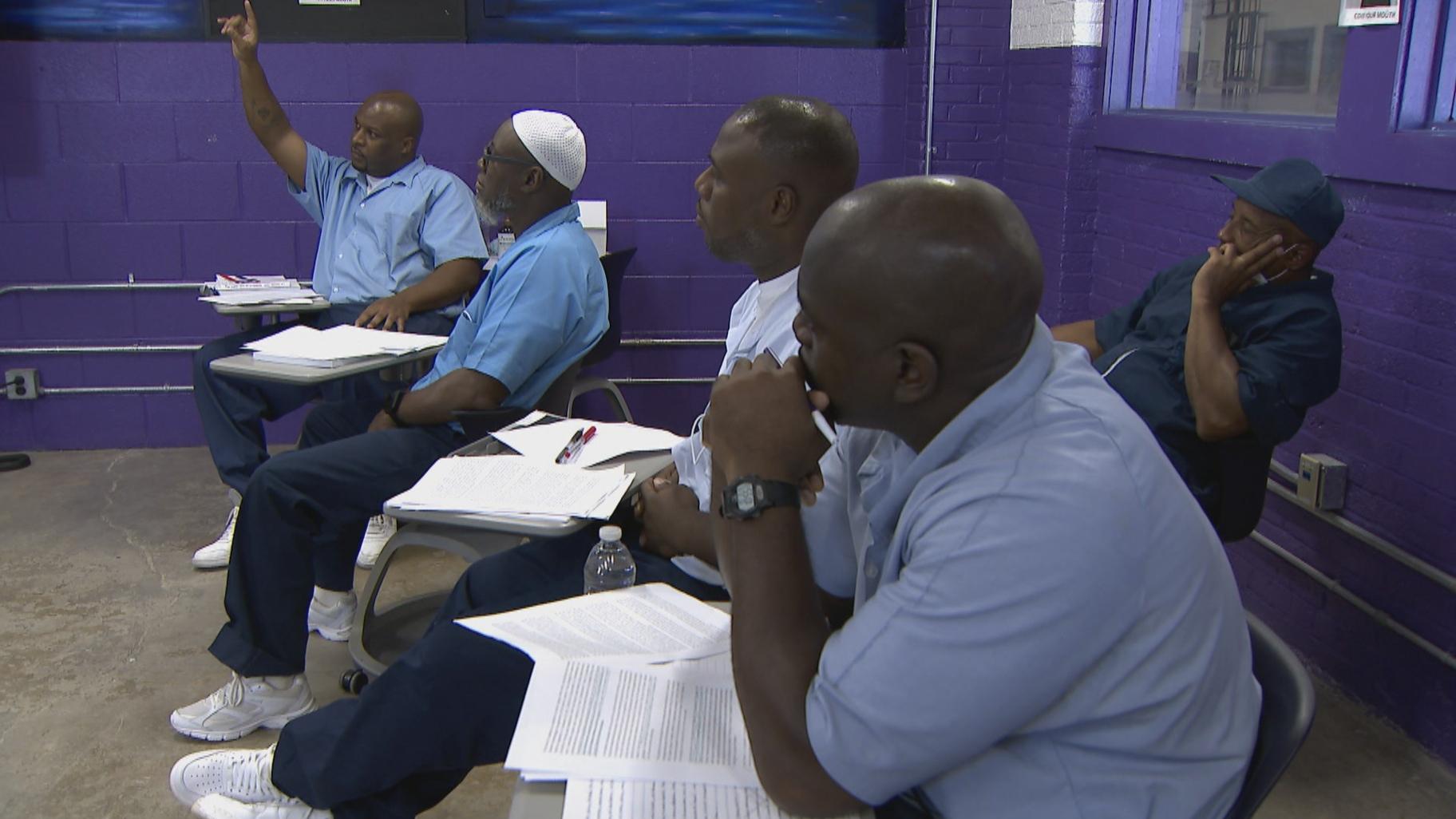

Past the prison walls and guard towers – constant reminders of freedoms lost – 16 men sit in a purple-paneled classroom. They’re discussing an article by legendary activist and author, Angela Davis, called “The Meaning of Freedom.”

The students themselves are serving prison sentences at Stateville Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison in Will County.

They are present, engaged and eager to learn.

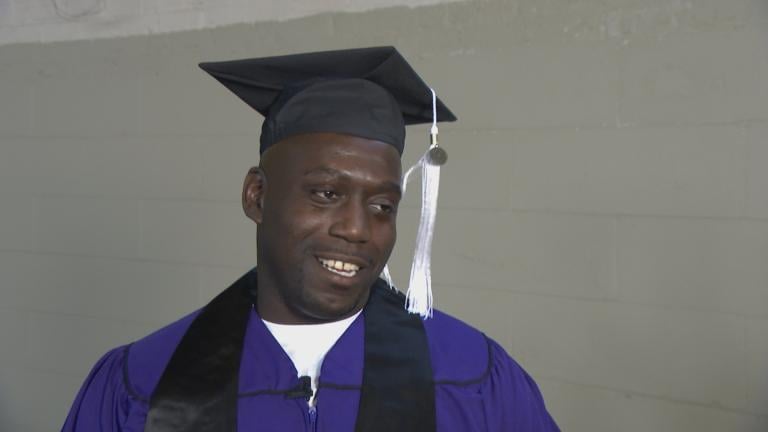

One of them is 43-year-old André Patterson, Dré for short.

Though he grew up in Evanston, the idea of attending Northwestern University as a student seemed unattainable. He referred to it as the “shining beacon on the hill”.

Patterson did get a job on campus as a dishwasher and busboy, but still fell into the wrong crowd. A story he shared in his personal essay when he applied.

“They came and arrested me at work and took me through this gauntlet of students and employees handcuffed,” Patterson explains outside his classroom at Stateville. “I used that as an example of the possibility of me now becoming a Northwestern student as like a full-circle moment for me.”

Though Patterson is 20 years into his 60-year sentence for murder, he’s taking every opportunity he can to learn.

Next year, he and his cohort will receive bachelor’s degrees from Northwestern’s School of Professional Studies through the university’s Prison Education Program, or NPEP.

Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that the overall rate of recidivism — returning to crime post-incarceration — is 67% nationwide.

NPEP cites data showing that that rate drops to 14% for someone with an associate’s degree, and 5.6% for someone with a bachelor’s degree.

Just like college, the NPEP students have papers to complete, but no computer to complete them on.

Men at Stateville Correctional Center participate in a class through Northwestern University’s Prison Education Program on Aug. 15, 2022. (WTTW News)

Men at Stateville Correctional Center participate in a class through Northwestern University’s Prison Education Program on Aug. 15, 2022. (WTTW News)

“There are all sorts of challenges. They don’t have access to the internet, they don’t have access to websites. Everything is handwritten,” explains NPEP director and founder, professor Jennifer Lackey. “If they have a question for the professor, if they don’t get a chance to ask it in class in real-time, they have to wait a week. They can’t email the professor … Getting a college degree is hard. Getting a college degree from Northwestern is hard. Getting a college degree from Northwestern while you’re incarcerated is nothing short of heroic.”

Lackey says the rigor in the Stateville classroom is no different than on campus.

But the school provides as many additional supports as possible, like tutors and study halls, to overcome what in many cases might not have been a solid secondary education.

What the university cannot control is time.

“The psychological challenge is really the main challenge because you have no control really over your study time, where and when you sit down and study,” Patterson explains. “You gotta grab snatches of solitude, snatches of comfortability, where I can set up. You have to do a whole choreography with your celly, and figure out what time works for him. It’s less control than the outside environment.”

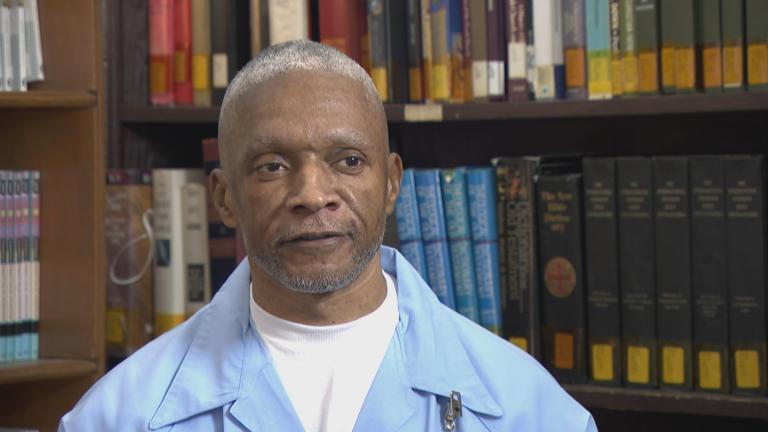

For Benard McKinley, 37, a sentence reduction means he could’ve petitioned for early release back in February.

But he chose not to.

“This is my safe place. When I leave the prison cell and that prison cell house and come into that classroom, I feel like I’m around my brothers,” McKinley says. “And being around my brothers, I’m able to be me.”

Today’s class is political philosophy and it’s clear, McKinley is among fellow philosophers in the room.

“Prison is more psychological than physical,” he says. “I’ve acquired so much at this point where to sacrifice maybe another 8-10 more months wouldn’t hurt. I feel like me being able to stay part of cohort and to finish education here, when I do go in front of the parole board, I will go in front of parole board with something to be proud of.”

But it will be a long time before some of McKinley’s classmates see the outside of Statesville prison — if at all.

Lackey argues there is still value in providing those inmates an education.

“We have a number of students who have natural life. While we hope for each one of our students there will be a legal pathway for them to go home one day, if it doesn’t turn out that way, we want to support them here,” she says. “So, once our students graduate from Northwestern with a bachelor’s degree, we hope to hire some of them to be tutors here in our program, to be teaching assistants. So, whatever that path looks like for you, we want to be there to help you achieve it. There is no dream that is too ambitious for us.”

Patterson, who grew up in the shadow of Northwestern, says earning his degree isn’t what he considers redemption.

“Redemption would be me taking everything I learned from the program and now applying it to my community. What can I do to put back where I’ve taken away?”

Patterson says he intends to write with his degree: books, short stories, maybe his own autobiography.

McKinley goes before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board in April for a hearing on his petition for early release. He’s studying to take the LSAT and wants to attend law school to become a civil rights attorney.

The team at Northwestern is even working to have the test administered while he’s in prison — that’s only happened once before in another state — so that after he earns his bachelor’s degree, and is potentially released from prison, in the spring, he’d be able to attend law school in-person in the fall.

Lackey says students who’re released before completing the program are able to apply for on-campus instruction.

But the handful of students who are on the outside choose to Zoom into their classrooms, partly, because they want to stick with their cohort. They also choose this route because getting to campus for classes is hard.

There are additional challenges they’re also managing: housing, job and food insecurity all stack up for them on the outside, and that makes prioritizing college a lot harder.

The school is currently taking applications for its third cohort at Statesville, this one open to inmates at prisons around the state. But there are only 20 spaces available.

There is a cohort of women at Logan Correctional Facility downstate.

Northwestern University funds the program, with some grant support.

But next year, the federal Second Chance Pell Program restarts, which will provide federal financial aid to incarcerated individuals, opening the door for more colleges and universities to provide prison education programs.

Follow Brandis Friedman on Twitter @BrandisFriedman