As members of Congress weigh potential measures to protect against mass shootings, one often-mentioned option is a so-called “red flag law” – a policy Illinois has in place.

The debate has taken on a sense of urgency after a gunman armed with AR-15 rifles recently killed 19 students and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

The shooter had previously exhibited problematic behavior, shared plans for a massacre on social media and displayed other warning signs.

Advocates believe that’s where red flag laws could have played a role.

Red flag laws are the “popular term for what members of the policy nerd brigade like me refer to as an Extreme Risk Protection Order,” said Jeffrey Swanson, with Duke University School of Medicine’s Psychiatry Department. Swanson also holds a faculty position with Duke Law School’s Center for Firearms Law.

“What it boils down to is, it’s a civil restraining order that gives police officers clear legal authority to remove firearms from a person who is manifestly posting a risk of harm to self or others at a particular time,” Swanson said. “But it’s not criminalizing, it’s a civil restraining order. But it’s temporary – it’s time limited.”

Under Illinois’ Firearms Restraining Order Act, guns can be stripped from someone a judge deems dangerous for a maximum of six months, a shorter timeframe than in other states’ laws.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have red flag laws.

State Rep. Kathleen Willis (D-Addison) sponsored the Illinois law in 2018.

“We passed it bipartisanly. The whole idea behind it is to be proactive – not to have to wait for a tragedy to happen, not have to wait for a hard-core threat where the police would get involved. But family members see, not always, but many times, these warning signals ahead of time,” Willis said. “I sort of put it as – not to be glib about it – but sort of as a country western song that your dog got run over, your wife left you and you lost your job. All those things one at a time you might be able to handle, but everything all at once could put you in a spin and you probably shouldn’t have a gun in your nightstand in those times.”

States’ measures differ, but in Illinois, only certain people can petition for a firearm restraining order, such as a close family member, spouse or co-parent or someone who lives with the individual.

Petitioners need not hire a lawyer or pay court fees; it’s intentionally a quick-turn. If a judge agrees that the petitioner has presented good evidence, law enforcement can temporarily take away the individual’s guns – which is a problem for Illinois State Rifle Association Executive Director Richard Pearson.

“Red flag laws undoubtedly violate the Fourth Amendment, which is unreasonable search and seizure,” Pearson said. “They haven’t had their day in court and all of a sudden the police comes and takes their firearms away, and they don’t know what’s happened.”

Illinois requires courts to hold a full hearing within 14 days, at which point a judge will decide if an initial two-week removal period should be extended to six months.

Pearson said while members of the Illinois State Rifle Association have successfully fought and won back their guns, it would be folly for them to go to court without a lawyer – so even if a gun-owner succeeds, it costs them time and money.

He also says an ill-meaning relative or ex-spouse could file a red flag petition out of vindictiveness.

Illinois law includes a provision that would allow someone to be charged with perjury if they file a petition with fraudulent evidence – a protection that Pearson said should be in any such act.

Texas doesn’t have a red flag law that would have allowed those close to him to seek action against the shooter before the mass shooting in Uvalde, but New York does and Pearson points out that didn’t stop the Buffalo shooter despite his exhibiting warning signs and extremism leading up to a racist attack at a grocery store in May.

New York’s governor on Monday signed a package of laws in reaction to the Buffalo mass shooting, including an expansion of who can file a protective order.

Swanson conducted a study that found for every 10 to 20 orders granted, one life was saved by suicide prevention.

So do they red flag laws work?

“It’s a very simple sounding question and I wish it had a really simple answer. I would say they can work and they do work, but I’m going to put some condition on it. Because they’re not going to work if you just pass the law and nobody knows about it and nobody uses it,” Swanson said. “They have to be implemented. There has to be some infrastructure around it. Or … you might as well take your new bill and put it in a bottle and throw it in the ocean and hope somebody finds it.”

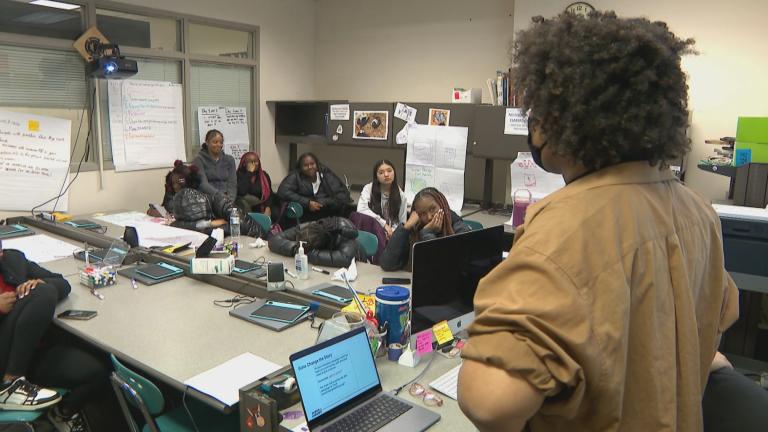

Enter state Rep. Denyse Wang Stoneback, a first term legislator now in a tight contest for re-election, who came into the General Assembly concerned people weren’t using this tool enough.

CBS News cites court documents showing emergency firearms restraining orders only 51 times in 2020 and 37 last year.

“Really we need to get the word out that people – there is something that people can do. If they hear of someone that is making threats,” Stoneback said. “We know that over half of mass shooters give at least one warning sign about what they’re going to do before they actually carry out these gun massacres. If we can get the word out that this is a resource, that this a tool in the toolbox that people have.”

Stoneback sponsored a law that took effect June 1 that will require police to be trained annually about Illinois’ red flag law, and that requires the state create a public awareness campaign.

The new state budget, set to take effect in July, allocates $1 million to spreading the word about it.

Follow Amanda Vinicky on Twitter: @AmandaVinicky