The new book “Parent Nation” makes the case for an overhaul of national priorities and family policy.

Author, Dr. Dana Suskind, is the cofounder of the TMW Center for Early Learning + Public Health at the University of Chicago and author of “Thirty Million Words.”

Suskind says her book offers a blueprint for a society that helps all families meet the needs of their children.

In the excerpt below, Suskind describes the basis of her work, and how it has evolved since its origins.

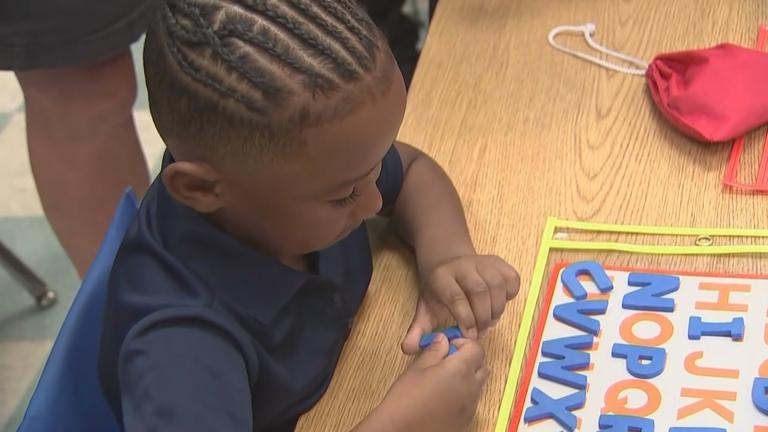

My team and I developed evidence- based strategies to show parents the importance of talking to babies and young children. Those strategies became the theme of TMW: Tune In, Talk More, and Take Turns, or what we call the 3Ts. Our work is centered on the knowledge that rich conversation is what unlocks a child’s potential and on the belief that parents as well as other loving caregivers hold the key during those early years. All adults—no matter their level of education, wealth, or work— can master the essential techniques for optimally building a child’s brain.

The idea, a straightforward approach to a complex problem, was intuitively appealing and a great success. It was the “magic bullet” that people were looking for and it took me to the nation’s capital, where I convened the first Washington, DC, conference on closing the word gap in 2013. Soon after, in 2015, I wrote a book called Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain, which explained what research has revealed about the role of early language exposure in the development of children’s brains. It was never just about the sheer number of words; but the difference between the effects of a lot of language exposure and a little served as a memorable representation of the brain-building strength of talk and interaction. The book caught on around the world. Everyone seemed to get its message. No matter the nuances of culture, vocabulary, or socioeconomic status, people had an almost instinctive understanding of language as the key to developing the brain to its maximum potential.

Yet the more deeply I engaged in this new work, the more troubled I became. Or, to put it more honestly, the more I came to realize how naive my ideas were, limited by my own comfortable life circumstances. I had thought the answers lay in the actions and beliefs of individual parents, in their knowledge and behavior. (I still believe those elements are critical!) And it followed that the goal should be to ensure, as I put it in Thirty Million Words, that “all parents, everywhere, understood that a word spoken to a young child is not simply a word but a building block for that child’s brain, nurturing a stable, empathetic, intelligent adult.” To that end, we were testing early language programs in randomized controlled trials—the scientific gold standard for determining what works and what doesn’t. We found that, indeed, our strategies worked and the science that supports them is solid. The programs we promote at TMW can—and often do—improve the lives of children.

But there was more to it than that. For our studies we recruited families, most of them low-income, from all over Chicago and later in other parts of the country. Our research followed children from their first day of life into kindergarten, and our programs took us into families’ homes and into their lives. I was getting to know people up close and over time. The parents’ enthusiasm was thrilling. They embraced the 3Ts with gusto, tuning in to their children, talking more as they went about their daily lives, and taking turns, encouraging their children to join the conversation. They wanted what we all want: to help their children get off to the best possible start. The problem was that the 3Ts took parents only so far. Real life would intrude, again and again and again.

There was Randy, who was excited to discover that talking about his love of baseball (Cubs only, never White Sox!) could help his son learn math but who had to work two jobs and, most days, had less than thirty minutes to spend with his kids. There was Sabrina, who gave up a well- paying job to care for her husband when he got sick and whose family ended up spending over two years in a homeless shelter, where she raised her two children, the youngest still a baby, in a stressful and chaotic environment. Most searing of all was the story of Michael and Keyonna, whose son, Mikeyon, missed out on all his father had to teach him for the first five years of his life because Michael spent that time in prison waiting to be tried for a crime he didn’t commit—not appealing or serving a sentence, mind you, just waiting for his case to be heard. Parenting is not done in a vacuum. Our research could not be, either. The circumstances varied, but everywhere I looked I saw the hurdles looming in front of mothers and fathers. At TMW, we can share with parents the knowledge and skills that build their children’s brains; but our programs do not substantially change the day-to-day lives of the parents who participate. The larger realities of a family’s circumstances—their work constraints, economic stresses, and mental health as well as the injustices and bad luck they are subject to—all matter as much as the 3Ts for healthy brain development. They either allow for the brain- building power of talk to occur or, if they limit the opportunities for engaging in the 3Ts, they stifle it like weeds choking the growth of a garden. When I saw just how difficult parenting is in a country that does so little to support the ability of parents to facilitate healthy brain development, I knew I had to learn more. I hoped I could do more.