(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

The coronavirus pandemic’s disproportionate impact on Black and Latino Chicagoans prompted state and local officials to prioritize hardest hit communities, dedicating resources to testing, surveillance, health care and vaccinations, among other things, in those communities.

But a new report finds that despite efforts to address racial inequities, vulnerable communities’ needs remained unmet.

“COVID-19, we found in our report, is not only an infectious disease, but it’s also exacerbated already profound economic, housing, education, health and mental health precarity of people on the basis of race, class and legal status,” said Claire Laurier Decoteau, a sociology professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and co-author of the report, at a virtual presentation on the report’s findings. “The toll on Black and Latinx communities has been profound.”

A hundred residents in three neighborhoods – Austin, Little Village and Albany Park – who were essential workers or lost their jobs due to the pandemic were interviewed between August 2020 and December 2021 for the report titled, “Deadly Disparities in the Days of COVID-19: How Public Policy Fails Black and Latinx Chicagoans.”

Researchers focused on those communities because they were facing high COVID-19 infection and death rates. The Little Village and Austin neighborhoods were also targeted by the city for additional resources.

In 2020, 1.75 out of every 1,000 Chicagoans died of COVID-19, according to the report, which found that number was significantly higher in Austin (2.24), Little Village (2.69) and Albany Park (2.73). That means a greater proportion of residents died in these communities than was typical for Chicago neighborhoods.

“In addition, Blacks and Latinx residents have experienced more layoffs, more lost work. They tend to be more behind on their rent,” said Laurier Decoteau.

Based on their interviews with residents and dozens of epidemiologists, health care providers and community organizers, researchers posited four reasons for the “disconnect between policies and residents’ experiences and needs.”

Those reasons include residents’ lack of a safety net, officials’ focus on treating the pandemic as a health crisis, an emphasis on protecting the economy at the expense of the vulnerable and barriers to accessing social assistance.

“Decades of discriminatory policies on housing, health care and social security, as well as disinvestment in poor neighborhoods has meant that lower-income and working-class Chicagoans did not have a safety net to rely on during the pandemic,” said Laurier Decoteau.

Even before the pandemic, fewer Black and Latino households had net worth than Whites. In 2011, 33% of Black and 27% of Latino households had zero net worth, compared to only 15% of White households, according to the study.

Black and Latinos didn’t have existing financial cushions, according to researchers, who said they were more likely to become infected with COVID-19 because they were more likely to be employed in low-paying, front-facing essential jobs.

Black and Latino Chicagoans account for the majority of front-line workers in the city.

Black and Latino Chicagoans account for the majority of front-line workers in the city.

In Chicago, nearly 36% of front-line workers were Black and nearly 26% were Latino, according to the report.

“This just shows us that there were disparities in who was working and who could not shelter at home, and (who) had to show up to work during the pandemic,” said Laurier Decoteau. “Black and Latinx workers are clearly over represented in front-line labor, and many of them had no choice but continue to work. They couldn’t stay home. They needed the job.”

The coronavirus pandemic has been treated primarily as a health crisis at the federal, state and local levels, according to researchers, and it has been fought through a series of public health strategies. But residents experienced the pandemic as a much broader crisis associated with housing, food, child care and employment insecurity.

“Within this pandemic, we have had so many other demics. This violence demics, the losin’ my job demic,” a Black woman from Austin told researchers. “It’s just been so many demics to add on, which causes more mental health issues.”

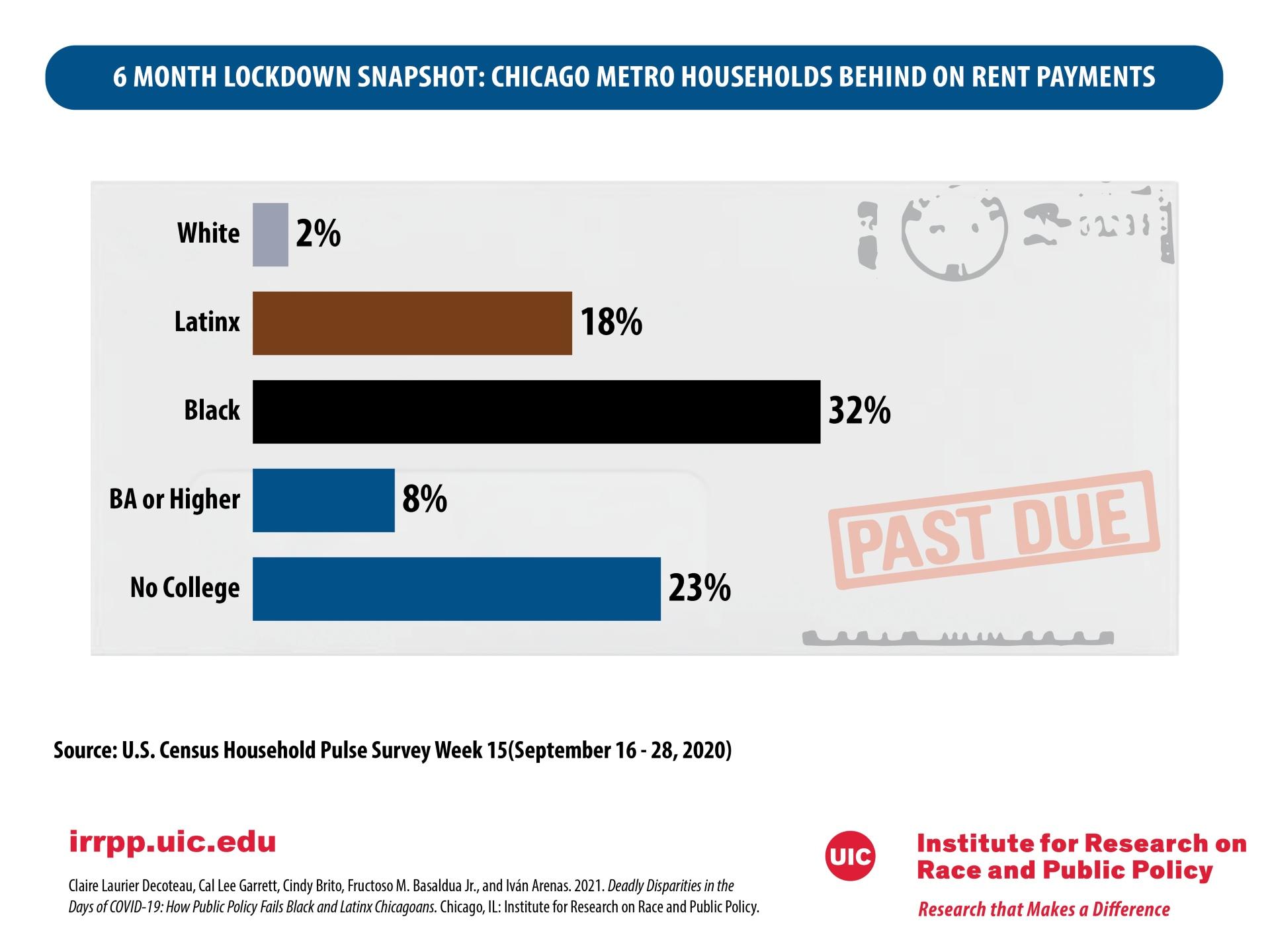

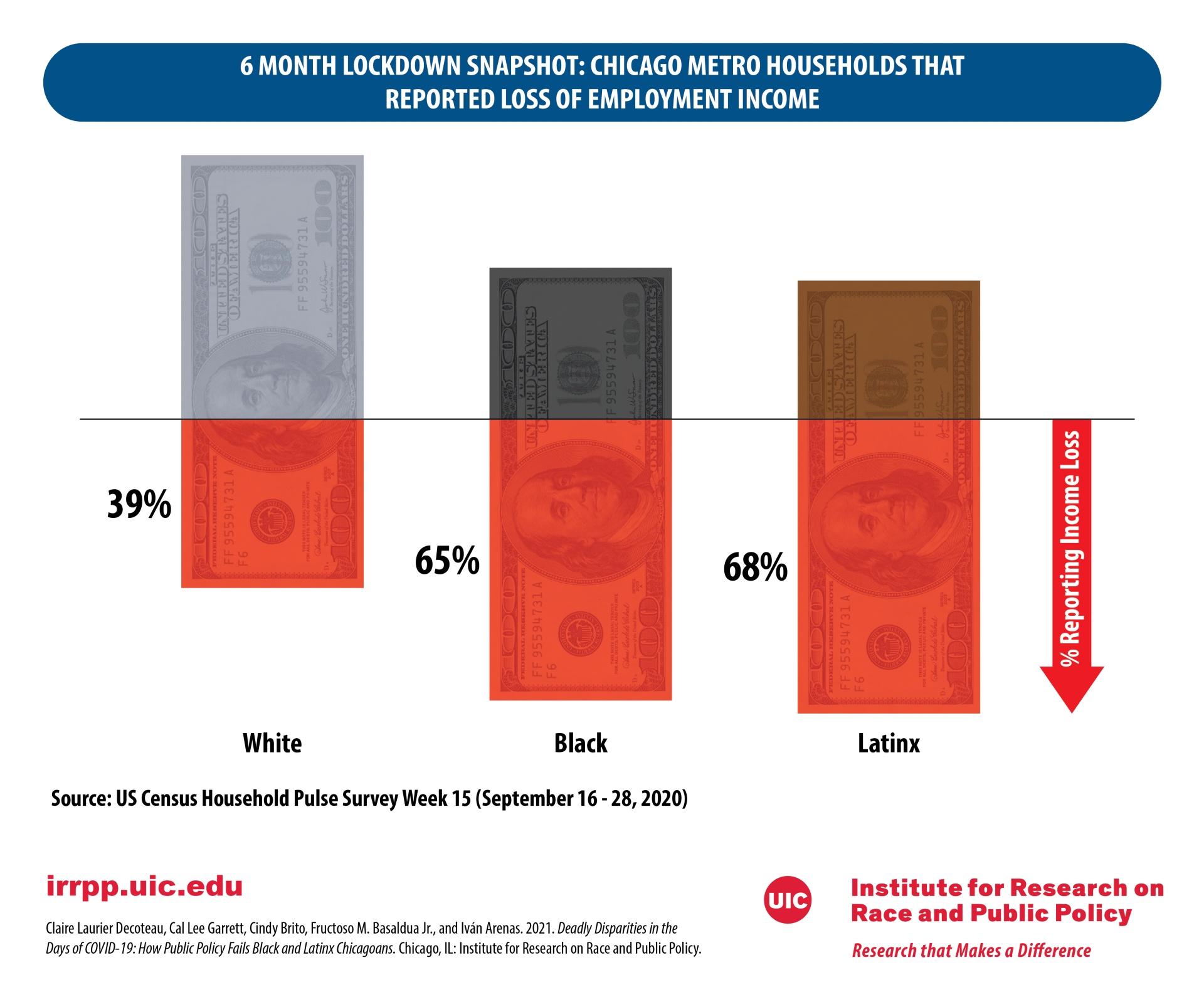

Six months into the pandemic, 32% of Chicago households that were behind on rent were Black, while 18% were Latino and 2% were white, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey. During that same timeframe, 65% of Black households and 68% of Latino households reported lost income, compared to 39% of whites, according to the survey.

In Chicago, Black and Latino households reported they were more likely to be behind on rent than their white counterparts.

In Chicago, Black and Latino households reported they were more likely to be behind on rent than their white counterparts.

Another reason why vulnerable communities’ needs were not met was because responses to the pandemic largely prioritized middle-class Americans and the protection of the economy over keeping vulnerable communities safe, according to researchers.

“Businesses were given extensive federal funding and cities often rushed to reopen their economies while residents were still in crisis and struggling to cope with pandemic vulnerabilities,” said Laurier Decoteau. “Labor protections and paid sick leave were often not prioritized, which put poorer Americans at risk of infection at work. Middle-class Americans were able to work from home largely because poorly paid workers continued to labor in factories, shipping warehouses, meatpacking plants, agricultural sites and along delivery routes.”

While social assistance was made available during the pandemic, including stimulus payments, increases in unemployment benefits and rental assistance, residents said they faced obstacles accessing assistance such as language barriers and technology issues. In addition, payouts were often extremely delayed, according to the report.

In order to receive housing and financial support, residents had to demonstrate an already existing vulnerability before resources would be allocated. “Implemented this way, social benefits include complex and often cumbersome requirements and bureaucratic proof to access, and this can create very harsh barriers for the most vulnerable,” said Laurier Decoteau.

Some residents said they didn’t have the necessary legal documents in order to receive support, such as contracts with landlords for rental assistance. A Little Village resident said many families don’t have contracts with their landlords and pay month to month.

Pandemic social assistance “really only constituted harm reduction when more extensive resource allocation was needed to offset existing structural inequalities,” said Laurier Decoteau. “Financial and housing support were offered in a reactive fashion after residents had already experienced mounting debt, job loss and financial insecurity, which often was very difficult for people to manage.”

During the first six months of the pandemic, more than 60% of Black and Latino households reported lost income.

During the first six months of the pandemic, more than 60% of Black and Latino households reported lost income.

Researchers argue financial and housing vulnerability were not treated as a public health risk for the poor, and people were pushed to continue to work and be housed in vulnerable conditions.

“Because the government did not design policies to keep poor people safe including cancelling rent, offering paid sick leave and work protections, providing cash assistance, and offering free medical treatment across hospital systems, poor people were forced to expose themselves to dangerous infectious situations at work, in public places, and at home,” researchers wrote in the report.

The report found the same issues locally. While city officials worked to address health inequities across Chicago neighborhoods, many residents told researchers they still struggled to access existing resources or that their broader needs remained unmet.

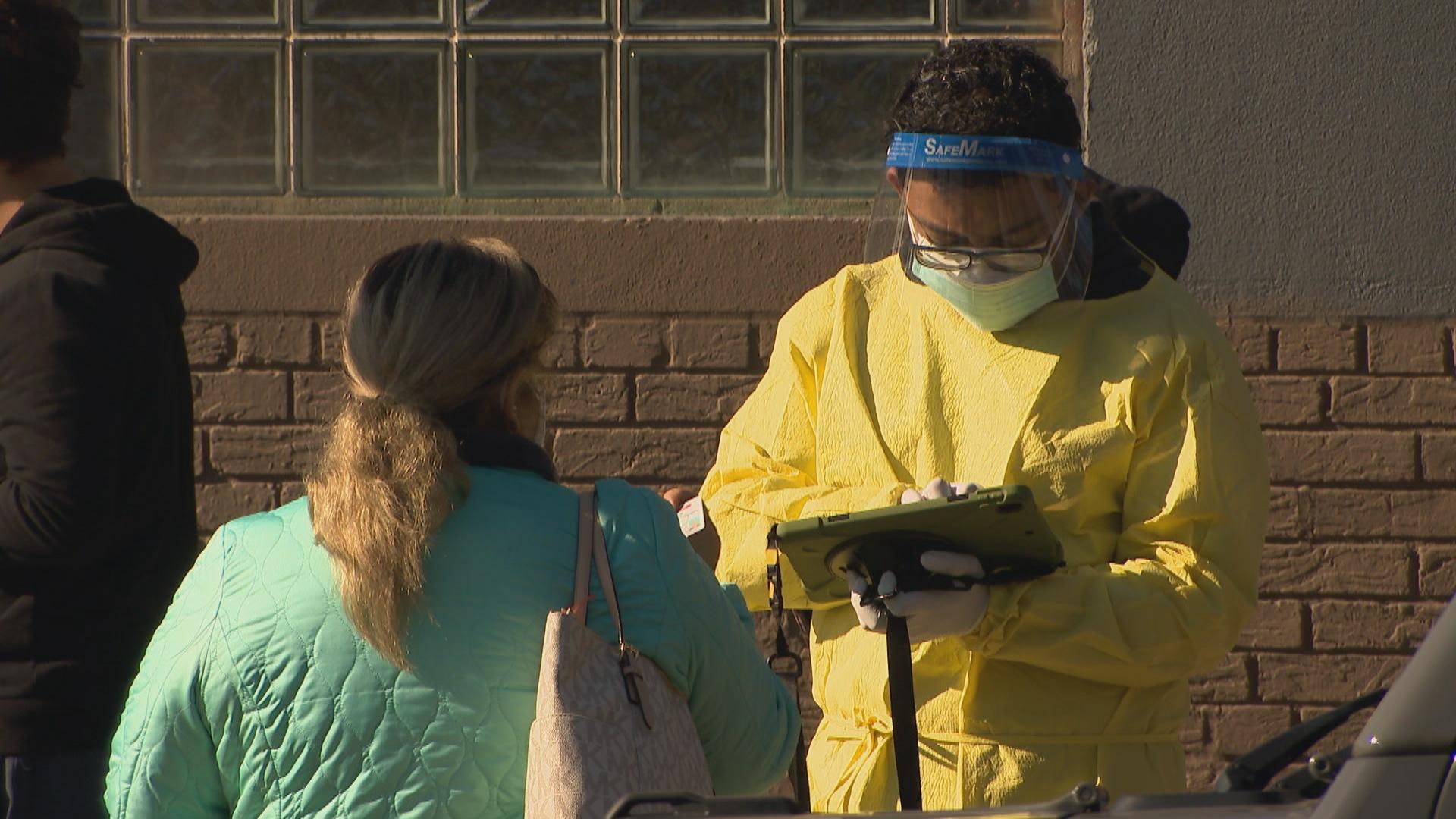

For example, city officials targeted high-risk neighborhoods with COVID-19 testing and vaccines, but programs failed to reach many residents, according to the report. Austin and Little Village residents told researchers they had difficulties accessing testing and vaccination sites. Organizers said those challenges were likely because promotional materials weren’t properly translated into Spanish, were advertised on social media that residents didn’t use or required registration and residents didn’t want to show proof of residency to city officials, according to the report.

“The residents we interviewed suggested that despite the city’s ‘hyperlocal approach,’ resources were not trickling down to all residents equally, and although certain organizations had the government’s ear and funding, others were struggling to meet high levels of community need,” researchers wrote in the report.

In a statement, the Chicago Department of Public Health said nearly 82% of eligible Chicagoans have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and that it is working to address inequities.

“Sadly, longstanding racial health disparities in Chicago and across the nation were very evident in the disproportionate impact the pandemic had on different communities. CDPH has been working to address these disparities for decades, and the City’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic focused on equity from the start, including the creation of our Racial Equity Rapid Response Team (RERRT),” CPDH said in a statement. “The RERRT brought together community leaders, public health entities, city government, and health institutions to help craft Chicago’s equitable COVID-19 response strategies and put those strategies into action. The result was resources dedicated to the most highly impacted communities, highlighted by our Protect Chicago Plus program.”

CDPH says it has also created Healthy Chicago Equity Zones (HCEZs) “as an extension of this racial and health equity work.”

“CDPH is allocating $9.6 million in COVID-19 relief funding from the CDC to establish these zones – six geographic areas covering the entire city led by regional and community organizations that are creating community-based stakeholder coalitions focused on targeted strategies to improve community and individual wellness for the long term,” the department said in a statement. “The HCEZs will help us better address the health disparities that were further amplified during the pandemic.”

Residents also expressed frustration that pandemic relief has been cut off before the pandemic has been fully resolved, according to Laurier Decoteau. “Many feel they’ve been abandoned to their conditions despite ongoing disruptions to work, ongoing infections and deaths, and ongoing debt and insecurity,” she said.

Researchers credit the city’s Racial Equity Rapid Response Team with its ability to collect and track epidemiological data on a hyper-local level, which allowed officials to direct testing, contact tracing and vaccines to vulnerable areas in the city and respond to surges and outbreaks with local supplies.

“And yet, historic patterns of inequality and segregation, lack of priority given to financial and housing assistance, and means-tested approaches to social assistance meant that many Black and Latinx Chicagoans suffered the worst impacts of the pandemic,” Laurier Decoteau said. “And vulnerable communities will continue to struggle to recover from the crises that were intensified by the pandemic as middle-class and wealthy communities recuperate and move on.

“In other words, this report suggests that exacerbated inequalities will be an enduring legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Contact Kristen Thometz: @kristenthometz | (773) 509-5452 | [email protected]