On July 10, 2018, 55-year-old Horacio Leon Junior took his bike to the lakefront near Jackson Drive.

“How he ended up in the water is still a mystery, but I do know that the water took him,” said Horacio’s daughter Jessica Leon. She says her father was in the water for seven minutes before bystanders were able to pull him out.

“For 13 days, he was in the ICU (at) Northwestern Hospital. On July 23, he passed away,” Leon said. “Since then, I’ve been working religiously to get water rescue stations placed along the shoreline.”

She’s not alone. Halle Quezada witnessed a 13-year-old girl drown at a Rogers Park beach in 2018. She says people on the shore searched frantically for anything that would float.

“It was just chaos in those moments, and there was absolutely nothing available to help,” said Quezada, who knows the girl’s family.

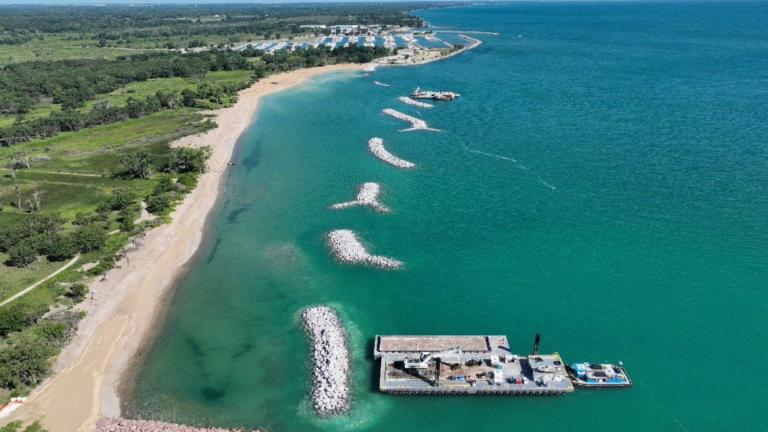

Quezada launched a petition and started publicly advocating for changes. Among other things, she wants water rescue flotation devices, like the life preservers already posted at harbors and near the river; restored lifeguard hours; and numbered beaches and break walls so people can easily provide their location to 911 if they call about a swimmer in distress.

“There are safety protections that are pretty easy and obvious that we simply don’t have,” she said.

In 2018, the city created a water safety task force that included Quezada. She says there’s broad agreement about the kinds of things that would make the lakefront safer, but after years of meetings there hasn’t been enough measurable change.

Now Quezada is going back to public pressure. A new petition has garnered more than 3,000 signatures. And she and Leon have been making their case directly to the Park District board. At an April board meeting, the Park District’s general counsel said adding life preserver rings along the lakefront isn’t so simple.

“When we do put up certain measures, you are increasing your risk of liability by representing that those areas … have been determined to be swimmable or usable areas,” said the Park District’s Timothy M. King. “From a legal standpoint, the best thing to do right now is nothing, because that's the only way to not take on that increased risk of liability.”

Nadav Shoked, a Northwestern Law professor who studies local government issues, understands the Park District’s position on flotation devices.

“Say they’re under-maintained and a person is using one of those life preservers and because it’s under-maintained he or she drowns,” Shoked said. “The Park District could be sued.”

Advocates say the answer to that is simple: maintain the equipment. But Shoked says the rescue devices are also problematic from a policy perspective, which the president of the Park District board echoed at its May meeting.

“Our argument is not about liability. What it really is, is about making sure that people are … observing the rules to not swim where they're not supposed to swim and at times they’re not supposed to swim,” said board president Avis LaVelle. “If we put these rings where we tell people not to swim that’s winking at us telling people not to swim there.”

But Quezada and Leon say people are already in the water when and where they’re not supposed to be. Others may not be able to read warning signage written in English. Some fall into the water.

“I’m not encouraging people to go into the water, but this is something that is needed,” Leon said. “If there would have been a life ring a water rescue station near where my father ended up drowning, no doubt in my mind (he would have survived).”

Advocates also say it’s an equity issue – that communities of color, particularly Black teen boys, are at a high risk of drowning. They also say installing rescue flotation devices is much less expensive than water rescues or medical care for someone who survives a drowning. And the Park District has more of its own counterarguments too – that most people in distress are too far from the shore or in too choppy of water for a life preserver ring to be effective, and that flotation devices are only effective if bystanders have training.

Since things with the Park District appear to have come to an impasse, Quezada says getting state and local lawmakers on board is likely the next step.

“If we can’t compel park districts to protect their kids (from) a leading cause of death for their age group, then we’ll look to compel them to protect our kids because they have to by law,” Quezada said.

The Chicago Park District did not respond to multiple requests for comment.