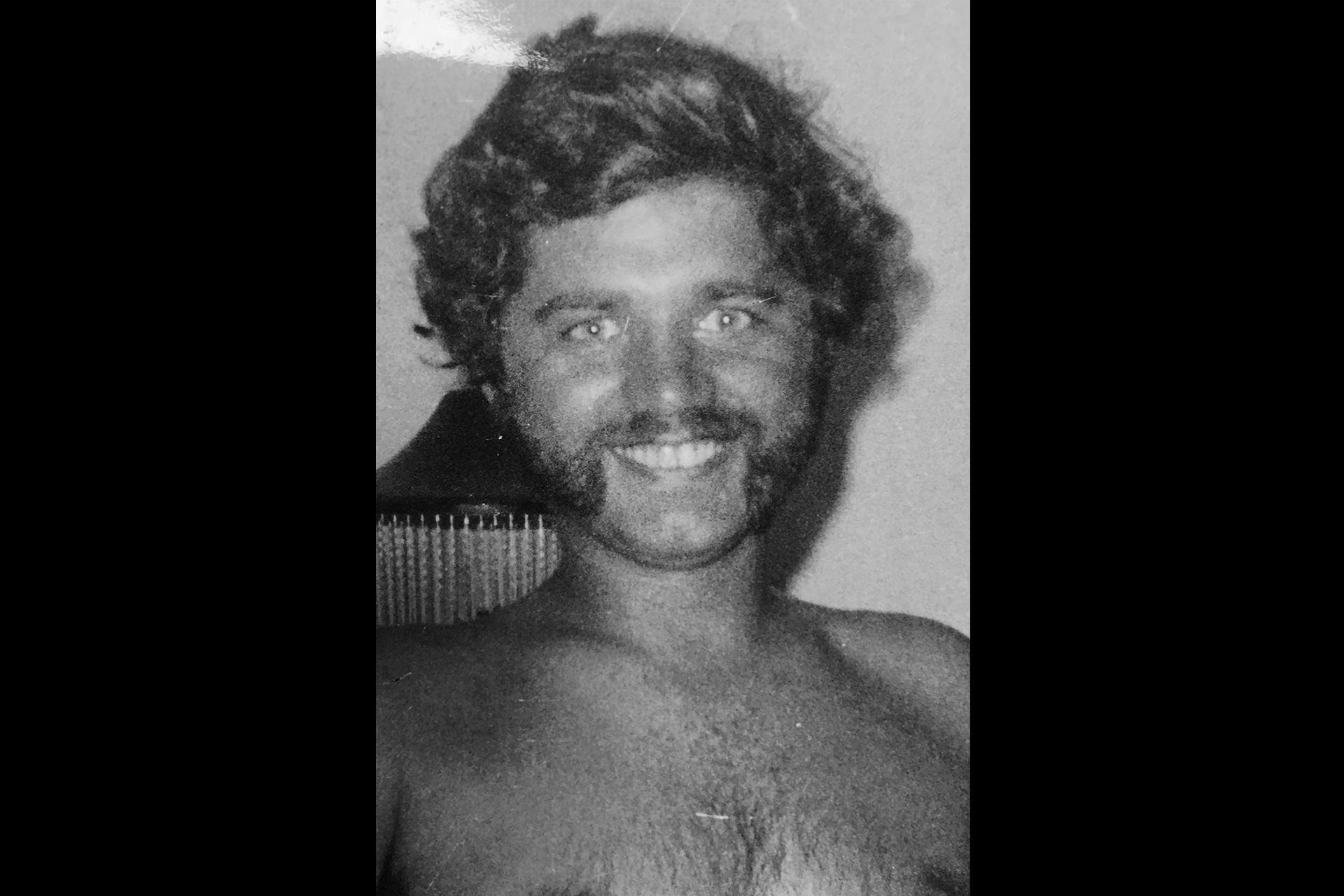

This undated photo provided by the Lisle Police Department shows Bruce Lindahl. (Lisle Police Department via AP)

This undated photo provided by the Lisle Police Department shows Bruce Lindahl. (Lisle Police Department via AP)

CHICAGO (AP) — When a police detective said last week that a man suspected of strangling a suburban Chicago teen in 1976 may have killed as many as a dozen girls and young women, the question that screamed louder than all others was: How did nobody notice?

Today, as Lisle Police Detective Chris Loudon and detectives in other communities where Bruce Lindahl lived try to retrace his steps, what is emerging is a terrifying murder mystery created by a man Loudon describes as a serial killer, a monster hiding in plain sight.

“Bruce stayed under the radar,” he said.

When authorities discovered Lindahl’s body, dead from a knife wound, in a Naperville apartment in 1981, he was known to various police departments as a loser who had been arrested many times but who had no felony convictions on his record. As with many serial killers, he was a loner, he didn’t have a wide circle of friends and he moved often.

He was also a “smooth talker,” Loudon said.

“We talked to women who said he could talk you into doing things,” he said. Many photos of naked women were discovered in Lindahl’s apartment after he died.

He also took pains to hide his actions. Of the females who investigators believe Lindahl abducted and killed, only two bodies have been found.

One was Pamela Maurer, the 16-year-old whose body was found next to a road in Lisle in 1976. Because she was found within hours of her death, DNA evidence remained on her body that investigators used — eventually — to link her death to Lindahl, whose body was exhumed last year. Lindahl tried to make it appear that Maurer had been hit by a car, police said.

The other victim was Debra Colliander, who disappeared days before she was due to testify at trial that she had been kidnapped and raped by Lindahl. By the time her body was found in a shallow grave on a farm two years later, any DNA evidence was long gone, a victim of the elements.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, detectives relied on electric typewriters and telephones, not sophisticated computer systems and cellphones. National databases detailing and connecting unsolved homicides or unidentified remains didn’t exist. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children was not created until three years after Lindahl’s death.

Loudon and other investigators have had to scour musty evidence rooms for typed or handwritten reports from that time.

Often, police departments only learned of similar crimes in neighboring communities by accident.

“What I’ve seen in cases from that time is a cop happens to catch a news blurb that someone got arrested and it rings a bell with another case,” said Kendall County Sheriff’s Detective Sgt. Caleb Waltmire, who is investigating Colliander’s death.

As concerns DNA evidence, the 1970s might as well as have been the Stone Age, and advances in forensics came slowly. In 1993, when the bodies of seven people were found shot to death in a cooler at a suburban Chicago restaurant, detectives bagged up a half-eaten piece of chicken and saved it in the hope that one day DNA analysis could unlock a clue. That chicken proved crucial in the 2007 conviction Juan Luna, one of two suspects in the killings.

There have also been advances in police procedure.

After the discovery of more than two dozen boys and young men in a crawl space at John Wayne Gacy’s Chicago-area home, law enforcement agencies were criticized for failing to connect the missing victims sooner. Their discovery prompted a concerted effort to share information on runaways and other people reported missing.

Police forces must now accept a missing person case immediately, rather than leaving a 72-hour grace period, said Cook County Sheriff’s Lieutenant Jason Moran, who led the investigation in which unidentified Gacy victims were exhumed so they could be identified.

Law enforcement must also confirm the return of a missing person by laying eyes on that person, Moran said. That practice wasn’t followed by detectives who believed a friend of a missing teen in the late ‘70s who said he had seen the boy. Police later discover that teen’s body among the victims at Gacy’s home.

Gacy was convicted of killing 33 young men and was executed in 1994.

Loudon said he has seen no indication as he reviews missing persons reports that police departments didn’t take missing person cases seriously around the time Maurer died. Nonetheless, as he reached out to the relatives of those reported missing, some told him his was the first call they have ever received updating them on their loved ones.

Moran is not surprised.

“The ‘60s and ‘70s with the sex and drugs and kids who put their thumb in the air to (hitchhike) to the beach for two weeks ... meant there were a lot of missing kids at the time and so the cases didn’t get the attention they really required,” he said.

Even less effort went into finding runaways.

“It’s not right, but once they heard this person has run away 10 times, there was a sense they’d return three days later,” Moran said.

Chillingly, it all added up to a perfect environment for Lindahl, if he was a serial killer, to stalk and capture his victims.

“Because of the culture, society, the drugs, the weak family bonds ... it was easier for serial killers to operate at that time,” Moran said.