He is a giant in comedy, and he was a big deal even as a child. Literally. John Cleese was six feet tall before the age of 12. He eventually stopped growing and used his considerable size to embrace humor that could be both physical and cerebral in popular shows like "Fawlty Towers" and "Monty Python's Flying Circus," to movies such as "A Fish Called Wanda."

His memoir "So, Anyway..." is now in paperback, and we are pleased to welcome John Cleese to "Chicago Tonight." Below, some highlights from our conversation.

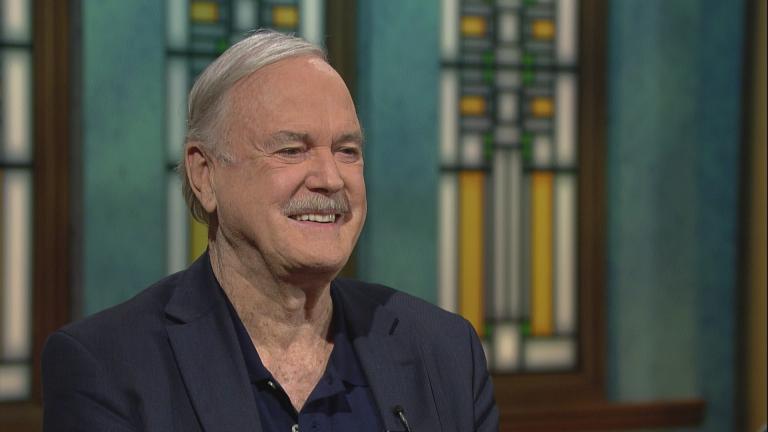

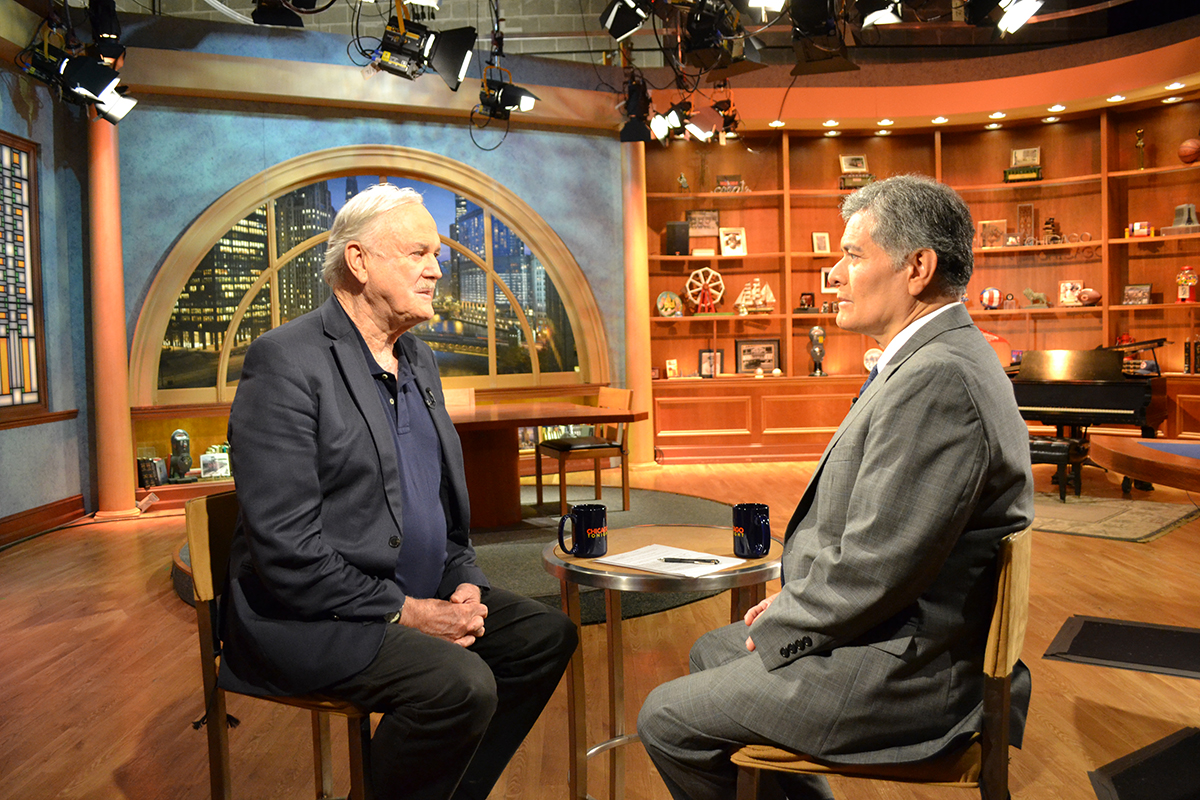

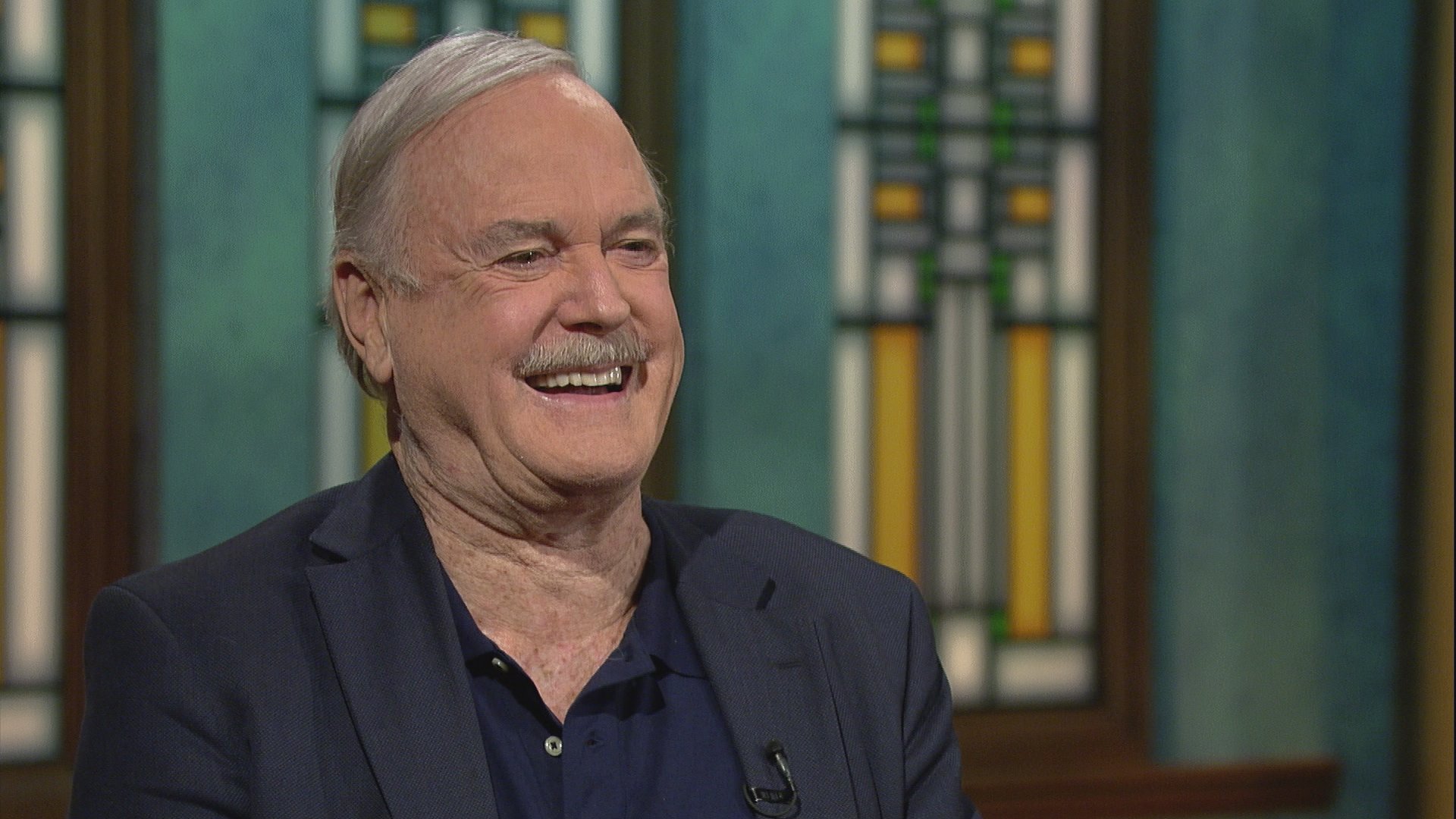

John Cleese on the "Chicago Tonight" set with Phil Ponce. (Chloe Riley)

John Cleese on the "Chicago Tonight" set with Phil Ponce. (Chloe Riley)

On the role of luck in his career

"I got into show business entirely by accident. Had a lot of luck. You know, the older I get the more I realize how much luck is so essential in life.

"I was in a show at Cambridge, and a very nice guy in a suit turned up, halfway through the second week–we used to do a show in the local professional theater–and he said, 'I want to put you on in London.' And they put us on [for] five months in London.

"Then I came to New York, and the show was very good, but we got one bad review. Guess where that was? New York Times. So we were off for three weeks. (Walter Kerr loved us. He was the greatest critic in America, wrote two pieces; wrote a piece specially to keep us alive.) So that was bad luck.

"But then David Frost calls me from London. He's the only guy in London who has any idea what I do, and the only guy in London who's big and powerful. And he calls me and says, 'Do you want to be on my TV show?' Absolutely out of the blue. I said, 'Yes, please!' And that was it, and I was in show business."

On the media

"I've done many many things. I was very pleased: I told one reporter for a joke that I was the minister of defense in the John Major government. And that my mother was an acrobat. You can get anything printed, especially in the Daily Mail."

On the success of 'Monty Python'

"I think it was just that we didn't take things seriously. The loveliest thing anyone ever said was quite early on after the first series had started to go out, and somebody said to me, 'What I find now is when I watch Monty Python I cannot watch the news afterwards. I cannot take it seriously.' And the lovely thing is, I've now reached that point where I can take almost nothing seriously. As one great English general said, 'Most things don't matter very much.' Most things don't matter at all."

![]()

Watch: Cleese plays the role of the Black Knight in the 1975 comedy "Monty Python and the Holy Grail."

"When my first leg was chopped off, then I was replaced by a genuine one-legged man," Cleese said of the clip. "He was a silversmith in the city of London. He did the hopping because he was so expert at hopping."

Flashback

In March 1998, Cleese appeared on "Chicago Tonight" with the show's original host John Callaway. Watch the full interview from our archives, below.

Below, an excerpt from "So, Anyway ..."

An excerpt from SO, ANYWAY…

By John Cleese

I made my first public appearance on the stairs up to the school nurse’s room, at St. Peter’s Preparatory School, Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, England, on September 13, 1948. I was eight and five-sixths. My audience was a pack of nine-year-olds, who were jeering at me and baying, “Chee-eese! Chee-eese!” I kept climbing the steps, despite the feelings of humiliation and fear. But above all, I was bewildered. How had I managed to attract so much attention? What had I done to provoke this aggression? And . . . how on earth did they know that my family surname had once been Cheese?

As Matron “Fishy” Findlater gave me the customary new-boy physical examination, I tried to gather my thoughts. My parents had always warned me to keep away from “nasty rough boys.” What, then, were they doing at a nice school like St. Peter’s? And how was I supposed to avoid them?

Much of my predicament was that I was not just a little boy, but a very tall little boy. I was five foot three, and would pass the six-foot mark before I was twelve. So it was hard to fade away into the background, as I often wished to—particularly later when I’d become taller than any of the masters. It didn’t help that one of them, Mr. Bartlett, always referred to me as “a prominent citizen.”

In addition, as a result of my excessive height, I had “outgrown my strength,” and my physical weakness meant that I was uncoordinated and awkward; so much so that a few years later my PE teacher, Captain Lancaster, was to describe me as “six foot of chewed string.” Add to that the fact that I had had no previous experience of the feral nature of gangs of young boys, and you will understand why my face bore the expression of an authentic coward as “Fishy” opened the door and coaxed me out towards my second public appearance.

“Don’t worry, it’s only teasing,” she said. What consolation was that? You could have said the same at Nuremberg. But at least the chanting had stopped, and now there was an expectant silence as I forced myself down the stairs. Then…

“Are you a Roundhead or a Cavalier?”

“What?”

Faces were thrust at me, each one of them demanding, “Roundhead or Cavalier?” What were they talking about?

Had I understood the question, I would almost certainly have fainted, such a delicate little flower was I. (And perhaps I should explain to the more delicately nurtured that I was not being asked to offer my considered views on the relative merits of the opposing forces in the English Civil War, but to reveal whether or not I had been circumcised.) However, my first day at prep school was not a total failure. By the time I got home I had learned the meaning of two new words—“pathetic” and “wet”—though I had to find Dad’s dictionary to look up “sissy.”

Why was I so . . . ineffectual? Well, let’s begin at my beginning. I was born on October 27, 1939, in Uphill, a little village south of Weston-super-Mare, and separated from it by the mere width of a road which led inland from the Weston seafront. My first memory, though, is not of Uphill but of a tree in the village of Brent Knoll, a few miles away, under whose shade I recall lying, while I looked through its branches to the bright blue sky above. The sunlight is catching the leaves at different angles, so that my eye flickers from one patch of colour to the next, the verdant foliage displaying a host of verdant hues. (I thought I would try to get “verdant,” “hues” and “foliage” into this paragraph, as my English teachers always believed that they were signs of creative talent. Though I probably shouldn’t have used “verdant” twice.)

Of course, I’m not sure it is my first memory; I’m sure I used to think it was; and I like to think it was, too, because it would make sense, baby me lying in a pram, contentedly watching the interplay of the glinting verdant foliage and its beautiful hues.

One thing I do know for certain, though, is that shortly before this incident with the tree, the Germans bombed Weston-super-Mare. I’ll just repeat that…

On August 14, 1940, German planes bombed Weston-super-Mare. This is verifiable: it was in all the papers. Especially the Weston Mercury. Most Westonians were confident the raid had been a mistake. The Germans were a people famous for their efficiency, so why would they drop perfectly good bombs on Weston-super-Mare, when there was nothing in Weston that a bomb could destroy that could possibly be as valuable as the bomb that destroyed it? That would mean that every explosion would make a tiny dent in the German economy.

The Germans did return, however, and several times, which mystified everyone. Nevertheless I can’t help thinking that Westonians actually quite liked being bombed: it gave them a sense of significance that was otherwise lacking from their lives. But that still leaves the question why would the Hun have bothered? Was it just Teutonic joie de vivre? Did the Luftwaffe pilots mistake the Weston seafront for the Western Front? I have heard it quite seriously put forward by older Westonians that it was done at the behest of William Joyce, the infamous “Lord Haw-Haw,” who was hanged as a traitor in 1944 by the British for making Nazi propaganda radio broadcasts to Britain during the war. When I asked these amateur historians why a man of Irish descent who was born in Brooklyn would have such an animus against Weston that he would buttonhole Hitler on the matter, they fell silent. I prefer to believe that it was because of a grudge held by Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering on account of an unsavoury incident on Weston pier in the 1920s, probably involving Noël Coward and Terence Rattigan.

My father’s explanation, however, makes the most sense: he said the Germans bombed Weston to show that they really do have a sense of humour.

Whatever the truth of the matter, two days after that first raid we had moved to a quaint little Somerset village called Brent Knoll. Dad had had quite enough of big bangs during his four years in the trenches in France, and since he was up to nothing in Weston that was vital to the war effort, he spent the day after the bombing driving around the countryside near Weston until he found a small farmhouse, owned by a Mr. and Mrs. Raffle, who agreed to take the Cleese family on as paying guests. I love the fact that he didn’t mess around. We were out of there! And it was typically smart of him to find a farm, where, at a time of strict rationing, an egg or a chicken or even a small pig could go missing without attracting too much attention.

Mother told me once that some Westonians privately criticised Dad for retreating so soon. They apparently felt it would have been more dignified to have waited a week or so before running away. I think this view misses the essential point of running away, which is to do it the moment the idea has occurred to you. Only an obsessional procrastinator would cry, “Let’s run for our lives, but not till Wednesday afternoon.”

Back to the tree. I revisited the farm many years later, and, just as I thought I remembered, there was a huge chestnut tree in the middle of the front lawn, under which I might easily have lain in a pram. In 1940 the farmhouse had been one of a row of houses of medium size strung along a road, with fields opposite; it didn’t look very farm-like from the front, but when you walked up the drive and got to the back of the house you saw there was a proper farmyard, with mud and chickens and rusty farm equipment and ferrets in cages and rabbits in wooden hutches.

And it was this location that provides my second memory. (It must come after the first because in it I am now standing up.) I was bitten by a rabbit.

Excerpted from So, Anyway… by John Cleese. Copyright © 2014 by John Cleese. Excerpted by permission of Crown Archetype, a division of Penguin Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Want more? Continue reading this excerpt.

John Cleese on the "Chicago Tonight" set with Phil Ponce. (Chloe Riley)

John Cleese on the "Chicago Tonight" set with Phil Ponce. (Chloe Riley)