Conservationist George Archibald has spent his life working to bring cranes back from the brink of extinction.

His groundbreaking work has been recognized around the world and was even featured on "The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson," which highlighted his extraordinary relationship with a crane named Tex.

Below, an extended interview with Archibald, co-founder of the International Crane Foundation in Barraboo, Wis.

Chicago Tonight: Why cranes? When and where did you interest begin?

George Archibald: My interest in cranes began when I was eight years old in a one-room classroom in Nova Scotia, Canada. There was a radio program about the discovery of the nesting grounds of the whooping crane in northern Canada. It was a dramatization, and the female crane was screaming that the airplane with observers had found their nesting areas – which previously were unknown. She said that soon the museum collectors would be there to shoot them. But her mate comforted her [by saying] that this was a protected area run by the Canadian government and that they were safe.

As a child, that program made a lasting impression. I followed the whooping crane story for years and eventually went to graduate school and studied crane behavior as my doctoral topic. I became aware of the endangered status of cranes worldwide and wanted to apply some of the things that had been done for whooping cranes in Canada and the U.S. to endangered cranes in Asia in particular, where there were so many endangered cranes at that time.

CT: When would this have been?

GA: This was 1954.

Below, a slideshow of cranes:

CT: What were the factors leading to the decline of crane populations?

GA: There are two underlying themes concerning the demise of the cranes: one is outright killing, which happened a lot in North America during the pioneer days when people lived off the land and a big bird was a big meal; and then habitat destruction in more recent years has been a problem. But still, the shooting of cranes is a huge problem that we are facing in the Middle East in particular today.

CT: Why so much shooting of cranes?

GA: The problem – after the Soviet Union fell apart in many of the former republics – there was a food shortage. There was a food shortage too in Russia during the 1990s and people were depending on their own resources to live … and shooting birds and the hunting of cranes in Azerbaijan destroyed the population of Siberian cranes that wintered in Iran. After the hostilities broke out in Afghanistan – when the Russians invaded Afghanistan in 1979 – there was proliferation of weapons throughout that region of the world and we lost the population of cranes. The last birds were seen in 2003.

CT: So are Siberian cranes extinct, or are they down to such small numbers that we never see them?

GA: They’re gone from what we call the western and central flyways that took them respectively to Iran and India. But we have a beautiful flock that winters in China. We have about 4,000 birds, but they are now critically endangered because the single lake where they winter is threatened by a damn that will elevate the water potentially 19 meters. So the battle goes on – in some areas it’s hunting, in some areas it’s habitat and in some areas it’s both.

Below, a video of sandhill cranes:

CT: What is it about cranes that maintains your fascination?

GA: Cranes are huge birds, they pair for life, they dance when they’re young when they are developing their pair bonds and they have calls that carry for miles. They have a special charisma. There’s nothing a crane does that is not graceful. They are important in so many cultures as symbols of long life and other good things, and they just have a fascination to people worldwide, and because of that interest in cranes they are wonderful ambassadors for conservation programs for wetlands and for grasslands; and because they migrate across continents they are a perfect vehicle for international cooperation. For example, our foundation is very involved in North Korea, and we are the vehicle for communication – through cranes – between North Korea and South Korea.

CT: How were you able to gain access to North Korea?

GA: There are a couple of million Koreans living in Japan with North Korean passports that can go and come between North and South Korea. And through scientists within that community I was able to get an introduction to colleagues in North Korea. (Because I’m a Canadian I can get a visa to go to North Korea.)

CT: What has that working relationship been like?

GA: I have a wonderful group of colleagues, kindred spirits that love nature and everything that it represents as much as I do, and I concentrate on our work, which is helping the farmers develop organic farming techniques so that there’s enough food for themselves and a surplus for the birds. And we were able to bring this practice of organic farming into North Korea by importing nitrogen-fixing plants and seeds from China, and now we have a model area where people from all over North Korea come to learn about organic farming. And because we had an interest in the people and their welfare, the people in turn were very open to wanting to help the cranes.

Cranes have particular significance in North Korea culturally, but we believe that during the food shortages of the 1990s – when we believe as many as 2 million North Koreans starved to death – likely cranes were hunted as well. But the cranes moved out of North Korea and into the demilitarized zone between the North and the South. But now South Korea wants to develop this area where the cranes live into factory zones and their habitats will be lost. So we are trying to be proactive in redeveloping places to ensure there are places in North Korea for the cranes to come back to. And it all rests with the local people and our model farm and we have had a wonderful relationship with the people and our researchers there. So although there are political complexities in the world, by concentrating on things of common interest we can make a lot of progress and I hope that cranes are a good example for many other areas of cooperation in difficult circumstances.

CT: How recently have you been to North Korea?

GA: I have gone to North Korea every year since 2008. I started our relationship in 2005; we met in China. I didn’t go last year – because of the Ebola crisis North Korea insisted that all visitors spend three weeks in a hotel being tested for the disease and that wasn’t something I wanted to do. I’m planning to go back this December.

Below, a video of sandhill cranes in flight as the sun sets:

CT: What is the favored habitat for cranes?

GA: Most of the cranes are very dependent on wide expanses of shallow wetlands. Of course these wetlands are on very fertile ground which, when it is drained, can very easily be turned into agricultural fields. So that’s the biggest threat, particularly when breeding: just one pair of cranes will require many acres of wetlands as their territory because they feed their young the animals that they find in the wetlands – bugs, fish and such. And they are a top carnivore during the rearing period. After the chicks are fledged after about three months they gather in flocks and feed opportunistically.

Below, a video of whooping cranes in the wild:

CT: What is the status of the whooping crane now?

GA: There are several populations now. There is the traditional flock that migrates from northern Canada to Texas, covering 2,500 miles on each migration across the continent. They number about 310 birds, they were reduced to just 15 birds in 1940 – it’s a remarkable recovery.

We have two experimental populations, one that that migrates from Wisconsin and migrates right over Chicago and they winter in southern Indiana and from there all the way to Florida. The other group is non-migratory in southwestern Louisiana where there are huge wetlands and where whooping cranes nested in the wild up until 1939. (They were wiped out by hunting but now the environment down there is much better.) We have 29 birds so far in the new flock in Louisiana and we are planning to release this year about 20 birds into Wisconsin and about 12 in Louisiana – and these are all birds from eggs produced in captivity.

CT: Why are some migratory and some non-migratory?

GA: It’s a very complicated phenomenon and we don’t really know how it happens, but we know that if a bird learns to fly in a particular area the so-called GPS in its brain is set to return to that area to breed. And if we release birds in Louisiana and they learn to fly in the wilds around Louisiana and they don’t have any migratory experience, they become a 100 percent non-migratory.

However, when we raise them in Wisconsin they migrate south following either sandhill cranes or ultralight aircraft – which we do with some of our birds. They have their GPS set for Wisconsin, but because of the winter they’ve got to get out of here so they undertake migrations.

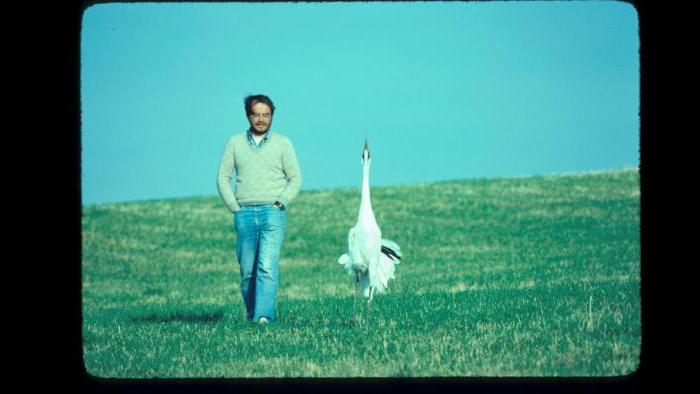

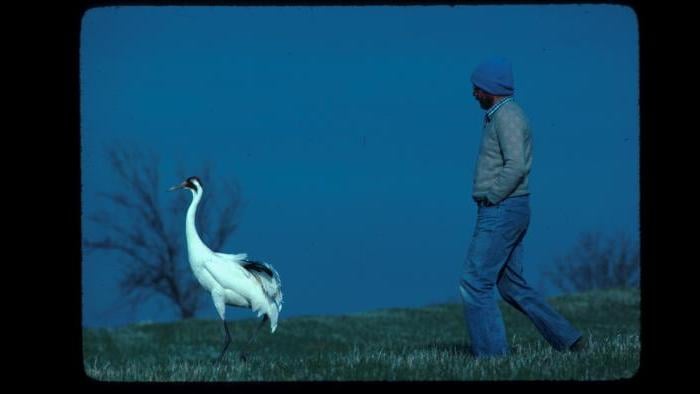

CT: Tell us the story of you and Tex.

Below: A video showcases Archibald’s relationship with Tex:

GA: My work with Tex is sort of metaphorical to the complexity and patience that we need worldwide in working with these birds. It all started in 1976, when as a 10-year-old, Tex was sent to our facility near Baraboo, Wisc. She was imprinted on people; she had been raised in a zoo. She didn’t see cranes during that critical imprinting period – which we think lasts about three months. So I would work with that bird in the spring. I would spend a couple of months with her. I had a little shack out in the fields and I would work on my papers and she would be in the fields by my shack. I had a bucket of water and a bucket of pellets for her, and she would look at me and make a special type of call which means “please follow me,” and I would follow her and she would go into the courtship dance and I would jump around and flap my arms and run with her for few minutes – it was quite exhausting actually – and I became here surrogate pair. So we imported some fresh semen from a center in Maryland and every year we failed – from 1977 when she laid her first egg and until 1982. And she would only lay one egg a year.

Today, we have the offspring of Tex, named Gee Whiz, and he is the father of many, many [cranes] which have been released into the wild. But he’s still producing at the Crane Foundation. About three weeks after he hatched, Tex was killed by a raccoon.

CT: That must have been heartbreaking. You must have formed a real emotional bond with Tex.

GA: I’m afraid it was a one-way street. It was a long and boring activity, although I admire whooping cranes and everything. She was like a pet and of course you get attached to a certain extent, but it was quite an ordeal to spend all of those weeks with her every year.

www.kKoontz.com

Crane Chasing

www.kKoontz.com

Crane Chasing

Last fall, Jay Shefsky visited Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area to witness annual southern migration of sandhill cranes.