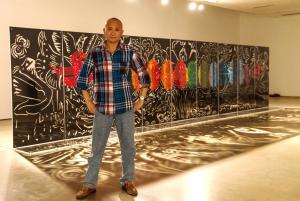

An art professor and artist, Qiao Xiaoguang, in China created 15 panels of intricately cut paper depictions of iconic Chicago landmarks. Places such as Navy Pier and the Willis Tower are paired with familiar landmarks in Beijing, such as the Forbidden City and Olympic sites. The originals are on view at The Field Museum in an exhibit called City Windows, and facsimiles are in Terminal 1 at O'Hare International Airport. We revisit the story.

View a panorama of City Windows.

Read an interview with Jan Leaming, owner of onemoon gallery, where many of Qiao’s works are showcased in Beijing.

Why did Professor Qiao choose to focus on Chicago as the subject of papercut artworks?

It really started with Mayor [Richard M.] Daley, who knew Jerry [Adelmann, the nonprofit leader behind the commissioned project]. The idea was promoting the relationship between contemporary Chicago and burgeoning China. The Hyde Park Art Center funded a trip for Professor Qiao to come to Chicago in 2011, and we spent a week in Chicago. There was this discussion about public art in O’Hare so we did take professor Qiao out there to show him the spaces. He chose those 15 windows. At that point, we had no idea what the subject would be. He originally wanted to do it with a bunch of iconic Chicagoans or Illinois people: an Abe Lincoln, an Oprah Winfrey, a Mr. Quaker Oats. There was going to be an Obama. It would be whimsical, like caricatures. He drew them and cut them. It turned out they didn’t read very well.

But when he came into Chicago on that exploratory trip, he was constantly taking pictures, like any good artist. He went home with maybe 1,000 photos, edited them, and picked out landscapes. He knew which ones in Beijing he wanted to feature but didn’t really know about Chicago. So Jerry contributed, I contributed, we did research, and picked the landmarks.

What did Professor Qiao think of Chicago?

He loved that Chicago is just a giant melting pot with all the different neighborhoods. Here’s a funny story: we were walking downtown and he asked me, “Do people in Chicago not believe in God?” And I said, “Why do you think that?” And he said, well, the tops of all these skyscrapers are flat. In traditional Chinese architecture, the roof usually points to heaven to indicate some relationship to heaven.

Was it difficult for him to make Western structures in an Eastern form?

No, no, no, he can do anything. He cuts everything. When you’re visual like he is, he has the skills to cut anything. An animal, a tree, a building, a mythological creature, a butterfly – he can do anything.

How did he become so skilled in papercutting?

He went to the Central Academy of Fine Arts for his bachelor’s degree. He learned to draw and sketch well. He became more interested in folk art and the belief systems in ancient Chinese art, particularly a lot of the things that come from minority cultures. Traces of Daoism, local gods, local signs and symbols—it’s all there in the papercuts. He can tell which cuts are, for example, Miao because of the presence of certain symbols and beliefs. They have different stories.

He spent his life visiting minority cultures during Chinese New Year, which is when papercutting occurs. They’re created for the New Year and the people stick them around on the doors. He’s spent time with 28 of the 57 ethnic minorities in China. He takes master’s degree students, and they go in and live there, and drink and eat and talk and cut.

Can you tell me about the differences in papercutting styles, which I understand vary from region to region?

They differ in content and color. Minority cultures cut with red paper or white paper. They’re not anything like what Professor Qiao does. What he does is much older, cutting in black. He is trying to keep the tradition alive because it is so Chinese. It’s all about positive and negative space, which is so important in the ink-painting tradition – what is painted and what is left black. The challenging part of cutting is a good balance of what is cut out and what is left intact.

You mentioned ink painting. Papercutting is described as a folk art associated with peasant women, for holidays and celebrations. It’s not an elite art form, venerated like calligraphy or ink painting. Why is it valuable?

You mentioned ink painting. Papercutting is described as a folk art associated with peasant women, for holidays and celebrations. It’s not an elite art form, venerated like calligraphy or ink painting. Why is it valuable?

Why does an anthropologist value a piece of clothing or tool or vessel from the past? It’s part of culture. It was their way of making life lovely, to make life beautiful and civilized and shared.

For a long time, no one really respected Professor Qiao. All his colleagues became esteemed painters and he felt that he maybe made a mistake. But his passion was with this very old material. He teaches in the Department of Humanities at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He teaches papercutting but his main subject matter is old belief systems, often expressed in papercuts.

Papercutting goes back thousands of years in China. What is its status as an art form today?

Very few Chinese are interested. It’s changing. It’s not like contemporary Chinese art, like the Cruelty Movement, the very political art, the Pop Art that came out, the need to express political and social themes. Papercuts don’t have that element, they’re totally neutral. Chinese collectors are just becoming interested in papercuts but there’s no money in it. Around New Year’s, the manufacturers are making papercuts in mass and people just buy those.

What about in the countryside and among the minorities. Is papercutting still practiced?

Very, very little. Most of the people who do it are old, old ladies. It used to be passed down from mother to daughter.

Another contemporary papercutter Lu Shengzhong talks about the dynamic life cycle of papercutting, constant remaking and variation, and connects it to life. Is that something at play in Professor Qiao’s work?

Yes. We did an exhibit in 2010 that Professor Qiao wanted to call “Flowers of Nothingness.” The idea was that in the beginning of every year, there is all this hope for good health and prosperity, birth of children and marriages, and it starts out so happy and positive. As the year wears on, things inevitably aren’t so cheerful. There’s death and sickness and life wears on that rosy picture gradually. We see that reality in the papercuts in their literal disintegration. At the end of the year, the papercuts on the door are in tatters. Then, they put new ones on top of the old ones. It is about the transient. It’s very Asian to be accepting of all the seasons of life.

Tell me about the process that went into making the papercut panels.

Professor Qiao made a huge sketch, not to scale yet, and he decided what material goes in each window. It was important that the horizon lines connect all the way across. Then he drew them on tracing paper, actual size. And then he cut in duplicates. Sometimes he cuts one white and one black, you know the yin-yang thing.

[For the O’Hare reproductions], Professor Qiao cut the papercuts about 40 percent of the actual size they are. And Matt Binns, a guy who works in Chicago, knew about the process whereby they could blow the cuts up and print them on a clear kind of vinyl. The vinyl had this adhesive that they could just stick on the window.

What do you want viewers to know about Professor Qiao or papercuts?

He’s so playful. He’s a very respected professor but he’s like a little boy. He sits on the floor cross-legged without any shoes or socks on to cut. He has so many animals in his studios, two or three cats, a dog, turtles. It’s a very Chinese kind of environment. Once, we had an art collector in the studio and the roof was leaking. Professor Qiao had a bunch of tin cans catching the droplets. The collector was like, “Oh my god, I better buy some of this stuff before it’s ruined.” But he’s in there creating, in spite of the leaks, in spite of everything.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

View a gallery of Qiao's papercuts.

Back in 2012, we found out that our own Phil Ponce’s surprising hobby and newly discovered talent was creating papercuts of his own. Watch the story below.