Geoffrey Baer climbs the highest heights in Chicagoland, gets on his soapbox at Bughouse Square, and tours Chicago via World War I monuments in this week’s edition of Ask Geoffrey.

In the '50s, people would gather at a nearby park, referred to as "Bughouse Square" to hear informal speeches on a variety of topics. Whatever became of Bughouse Square?

Rosemary Lambin, Chicago

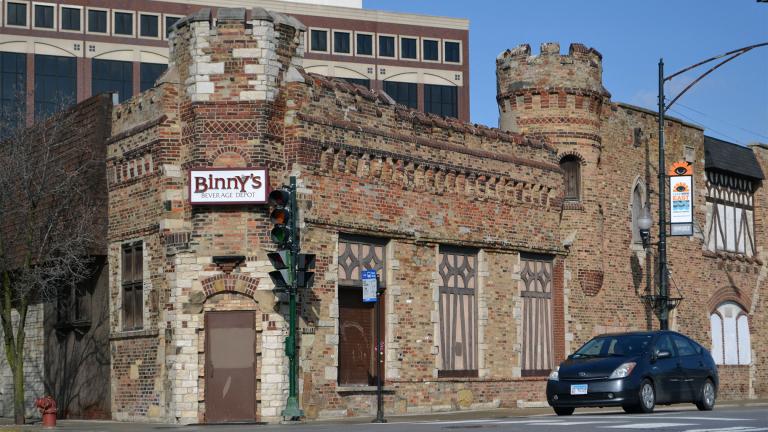

Bughouse Square is still there on Clark Street and Walton Street, right across from the Newberry Library. The park’s official name is Washington Square Park, but it became known as Bughouse Square after the slang for a mental health facility.

Bughouse Square is still there on Clark Street and Walton Street, right across from the Newberry Library. The park’s official name is Washington Square Park, but it became known as Bughouse Square after the slang for a mental health facility.

The park’s reputation as a home to fanatics began in the 1910s, when radicals and religionists alike would hop atop soapboxes to champion whatever their cause was to the gathered crowd. Topics ran the gamut from the plight of the working man to the morality of birth control. But speakers had to make their voices heard above the lively crowd, competing speakers, and lots of hecklers. One Chicago Tribune article described a speaker named One Armed Charlie who would begin his speeches by shouting, “Yabahabasheba! Yabahabasheba!” And while it was an open forum, most of the rhetoric at Bughouse Square had a decidedly radical bent. Socialists, anarchists, and labor organizers from the Industrial Workers of the World union were the crowd favorites.

Chicago icon and author Studs Terkel was a frequent listener and occasional orator at Bughouse Square. During Bughouse Square’s heyday in the '20s and '30s, Terkel’s family operated a hotel near the square. Young Studs would stop by to hear people like labor organizer and radical Lucy Parsons, whose husband Albert was one of the anarchists executed after the Haymarket riots. The experience Studs had at Bughouse Square was so formative to his worldview that he asked for his ashes to be scattered there.

The speechifying declined during the Red Scare of the 1950s, and its backlash against communists and socialists. By the mid-1960s, the gatherings were mostly a thing of the past.

But since 1986 the Newberry Library has bringing the lively Bughouse Square debates back for one day each year in summer. Speakers still climb up on soapboxes and get 15 minutes to plead their cases on everything from gun control to immigration reform. The champion speaker is awarded the Dill Pickle, named after the Dill Pickle Club, a nearby bohemian gathering space for regulars at Bughouse Square.

I scratch my head when I think about the name of Arlington Heights and Mt. Prospect, which have no appreciable elevation. How did they get their names?

Aaron Benson, Chicago

It’s certainly true that northern Illinois isn’t known for dramatic topography. In fact, in pioneer days, Chicago and the area around it was better known for being a soggy, flood-prone prairie. Developers looking to lure buyers to these new commuter suburbs northwest of Chicago chose names that reassured folks that the property was high and dry. This was also important to farmers, who were the majority of the buyers back in the 1880s when Arlington Heights was incorporated and Mt. Prospect was just getting its start. Another “high” town up that way is the lofty, snow-capped Park Ridge.

It’s certainly true that northern Illinois isn’t known for dramatic topography. In fact, in pioneer days, Chicago and the area around it was better known for being a soggy, flood-prone prairie. Developers looking to lure buyers to these new commuter suburbs northwest of Chicago chose names that reassured folks that the property was high and dry. This was also important to farmers, who were the majority of the buyers back in the 1880s when Arlington Heights was incorporated and Mt. Prospect was just getting its start. Another “high” town up that way is the lofty, snow-capped Park Ridge.

We wondered whether there was any truth to the marketing, so we did a little digging. According to City-Data.com, Chicago in general is just about 600 feet above sea level. Arlington Heights clocks in at 700 feet above sea level. And Mt. Prospect? It's a whopping 665 feet above sea level. So while a 65 foot rise in elevation might be enough to keep you out of the swamp, it’s only in flat land like Illinois that it could be marketed as “heights” or a “mount.”

Should you be seeking the highest ground in Cook County, it’s not a spot that refers to its elevation in its name. It’s way up in the far northwest corner near Barrington, at a dizzying 830 feet.

Besides the beautiful monument on King Drive and the naming of Pershing Road, what other tributes to WWI can be found in Chicago?

Janet Mark, Naperville

The 100th anniversary of the start of WWI is 2014 – and we were proud to find that our city actually has quite a few World War I monuments and tributes.

The 100th anniversary of the start of WWI is 2014 – and we were proud to find that our city actually has quite a few World War I monuments and tributes.

In fact, two iconic Chicago buildings have names that honor World War I veterans. Municipal Pier, was renamed Navy Pier in 1927 to honor Navy personnel who served during WWI. Another one is Soldier Field. When it opened in 1924, it was known as Municipal Grant Park Stadium, but within a year it was renamed Soldier Field to honor WWI soldiers at the urging of Gold Star Mothers, an organization of mothers whose children had died in battle.

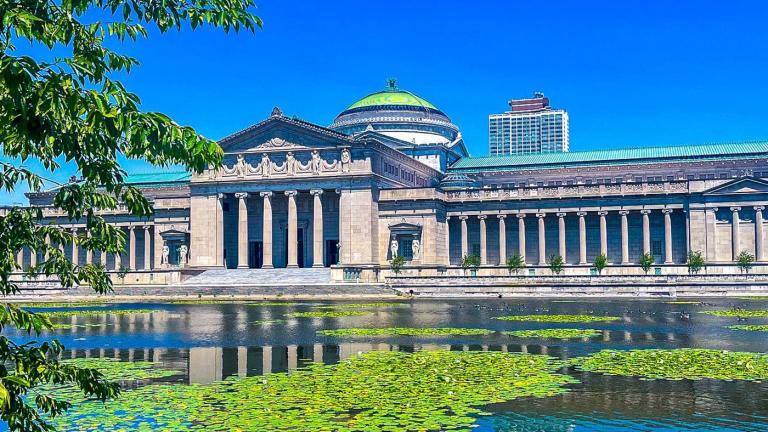

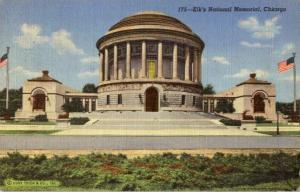

Not quite as prominent but still familiar to many Chicagoans is the Elks National Memorial in Lakeview. This spectacular design was the result of a competition to create a memorial honoring the members of the Order of the Elks who died during the Great War. The building also serves as the Order of Elks headquarters.

And there are smaller tributes sprinkled all over Chicago’s neighborhoods. The viewer mentions a monument on King Drive – she’s referring to the Victory Monument in Bronzeville honoring the Eighth Regiment of the Illinois National Guard, a regiment of African American soldiers who served in France during World War I.

On the northwest side in Edison Park, a granite memorial honors citizens of Edison Park who served in World War I.

In Pullman, another granite monument stands in tribute to doughboys who lost their lives in the Great War. It was originally topped with a bronze eagle, but the eagle was stolen. It’s since been replaced with a granite pyramid and had plaques added honoring fallen soldiers of other wars.

In Garfield Park, a marble pylon capped with a bronze flame stands to memorialize fallen World War I soldiers from the West Side of Chicago.

In the South Chicago neighborhood, Rainbow Beach and Park are named to honor the Army’s 42nd Infantry division, known as the Rainbow Division. This granite arch stands in the park to honor the Rainbow Division for their heroism while fighting in World War I.

A very modest World War I remembrance can be found on a street corner in Logan Square. At Francisco and Fullerton, a concrete base holds a bronze plaque inscribed with the names of around 50 people who made the ultimate sacrifice in the first World War.

Our viewer only asked about memorials in the city. Of course there are many in the suburbs as well, such as the sprawling Cantigny Park in Wheaton, which is essentially Col. Robert McCormick’s living memorial to the Great War. And there are many no longer standing, like cannons and tanks that were melted down for the WWII effort.

Also of note: the Newberry Library has a series of exhibits starting this month through January exploring Chicagoans’ experience in the Great War.