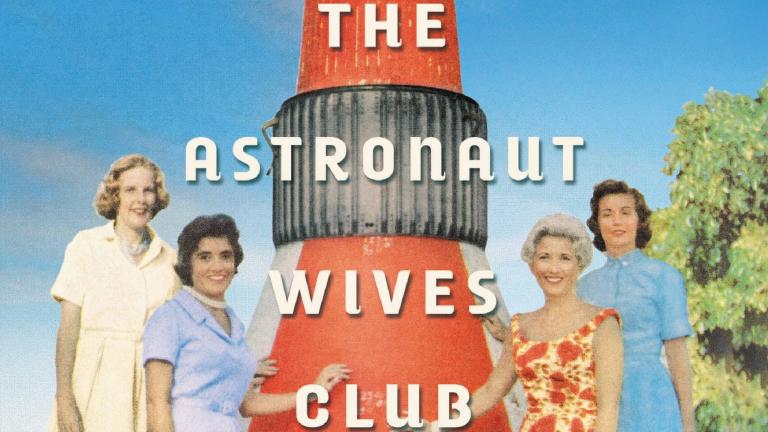

While NASA astronauts were lauded as American heroes, it was up to their wives to present the facade of a perfect family life. In her new book, The Astronaut Wives Club, author Lily Koppel tells the story of the dozens of women who tried to maintain normalcy as the nation scrutinized their every move. Koppel joins us on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm.

The story of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions has been told countless times, perhaps most famously in Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. But Koppel says those accounts have failed to capture the families the astronauts left behind.

The story of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions has been told countless times, perhaps most famously in Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. But Koppel says those accounts have failed to capture the families the astronauts left behind.

“I was on a Mad Men kick at the time, and was looking through Moon Fire by Norman Mailer, and looking at all these images we associate with space exploration,” she says. “I turned the page and saw these Astrowives with Pucci mini dresses and beehives and couldn't believe we’d never heard their side of the story before.”

The wives of the first seven American astronauts--the Mercury Seven--became overnight celebrities. As soon as their husbands were announced as the country’s first astronauts, reporters and TV crews were camped out on their front lawn and accosting them in the grocery store. They even had reporters and photographers from LIFE magazine embedded in their homes, part of a $500,000 exclusive deal to tell their story.

“They were America’s first reality stars,” Koppel says. “There was an incredible spotlight on their everyday lives. You had reporters embedded in their homes during the launches watching [them] like a time bomb. From the first day they were announced in 1959, all of the reporters were less concerned about why the astronauts were volunteering, but more concerned about what their wives thought.”

So much attention was paid to the astronauts wives because of how tight-lipped the former military pilots were. Trained not to show emotion, reporters often got short, unrevealing answers from the Mercury Seven.

So much attention was paid to the astronauts wives because of how tight-lipped the former military pilots were. Trained not to show emotion, reporters often got short, unrevealing answers from the Mercury Seven.

“The human interest of the story was going to lay with the women,” Koppel says. “When reporters realized they wouldn’t [answer] how it would smell on the moon, they turned to their wives.”

But the media scrutiny caused some of the wives to close up as well. NASA administrators demanded a serene family life from all the astronauts, and threatened to withhold space flight without a happy marriage. Of course, the prospect of watching as your husband rode a repurposed missile into space was a source of intense stress--not to mention that several of the astronauts were serial philanderers.

“The book is really about cracking the facade they had to present as a perfect American housewife,” Koppel says.

Read an excerpt from her book below:

To be an astronaut wife meant tea with Jackie Kennedy, high society galas, and instant celebrity. It meant smiling perfectly after a makeover by Life magazine, balancing an extravagantly lacquered rocket-style hairdo, and teetering in high heels at the crux of the space age.

The astronaut wives were ordinary housewives, most all of them military wives living in drab housing on Navy and Air Force bases. When their husbands, the best test pilots in the country, were chosen to man America’s audacious adventure to beat the Russians in the space race, they suddenly found themselves very much in the public eye.

As her husband trained for every possible aspect of spaceflight, each woman had to prepare for the day when she would have to face the television cameras, when the world would be scrutinizing her hair, her complexion, her outfit, her figure, her poise, her parenting skills, her diction, her charm, and most of all, her patriotism. She had to appear calm and composed while her husband was strapped atop what was essentially the world’s largest stick of dynamite, seconds away from being blasted off into space.

To help cope with the astronomical pressures of publicity, the wives couldn’t turn to their husbands, who were too busy training, or to NASA, which was too busy figuring out how to get their husbands to the Moon. So the wives turned to each other.

Louise Shepard, wife of the first American to go into space, had learned the hard way that she needed to prevent overeager photographers from pressing a lens to her window and sneaking a shot of her living room. Drawing curtains against the press was only the first of many tips, tactics, and secrets that would be passed among the astronaut wives, for enduring what was known to the public as the launch report, but which one of the wives renamed the Death Watch.

Years later, by the time NASA put a man on the Moon, this excruciating pageant, with the wives’ photogenic children, helpful neighbors, and publicity-seeking preachers, had evolved into a gathering somewhere between a celebration and a wake. In a singular Houston neighborhood known as Togethersville, this diverse group of women—over coffee and cigarettes, champagne and cocktails, tea and Tupperware, society balls and splashdown parties—shared laughter and tears, triumph and tragedy, as their husbands streaked through space.

The Astrowives learned that they needed to comfort each other during the agonizing minutes, hours, and days they had to wait at home for their husbands’ safe return to Earth. They brought potluck spreads—Jell-O molds, casseroles, frosted cupcakes stuck with little American flags, lasagna, deviled eggs, pigs in blankets, strawberry angel cake, marshmallow brownies, and homemade “Moon Cake,” a coconut cream pie topped with meringue swirled to look like the lunar surface. There was always champagne on hand, ready to be popped upon a successful splashdown. The wives dressed in their fashionable best: Doris Day–like finery for the Mercury missions, ’60s mod for Gemini, and ’70s suburban psychedelic for Apollo. Life magazine had been awarded exclusive coverage of the astronauts, and always sent its top photographers to cover them.

In the home of the lucky woman whose husband was “going up,” each wife was assigned her duty. One manned the coffeepot while another dumped out heaping ashtrays, chain-smoking being the occupational hazard of the Astrowives. Solidarity was essential; who but another Astrowife could understand what the wife of the moment was enduring? Of course the harrowing worry and stress was the wife’s alone. If she did ever care to share it, newsmen were stationed right outside, eager for a quote.

The ever-growing group of astronaut wives relied on each other more and more to negotiate their own roles at the forefront of history. As next-door neighbors in the space burbs, they kept each other grounded while their husbands headed to the Moon. “We formed our own traditions as we went along,” said Marge Slayton, who was essential in organizing the wives’ get togethers, “and they were good traditions.”

The astronaut wives instituted official monthly coffees and teas; everyone knew their unspoken promise: “If you need us, come.”

The story of the astronauts is well known, but this is the first time the wives’ story has been told. We have heard and seen so much about the technological aspects of the space race, but not enough about the extraordinary day-to-day lives the wives experienced behind the scenes.

This book tells the story of the women behind the spacemen, from Project Mercury of the Kennedy Camelot years (1959 to 1963, which launched the first American into space and eventually into orbit around the Earth), to the Gemini missions (1962 to 1966, notable for two-man space travel and the first U.S. space walk), through the Apollo program (1961 to 1972), which finally landed a man on the Moon.

Ultimately, the wives’ story is about female friendships and American identity. While their husbands were launched into space, they were being launched as modern American women. If not for the wives, the strong women in the background who provided essential support to their husbands, man might never have walked on the Moon.